By Ri J. Turner

Feminist Review

February 11, 2010

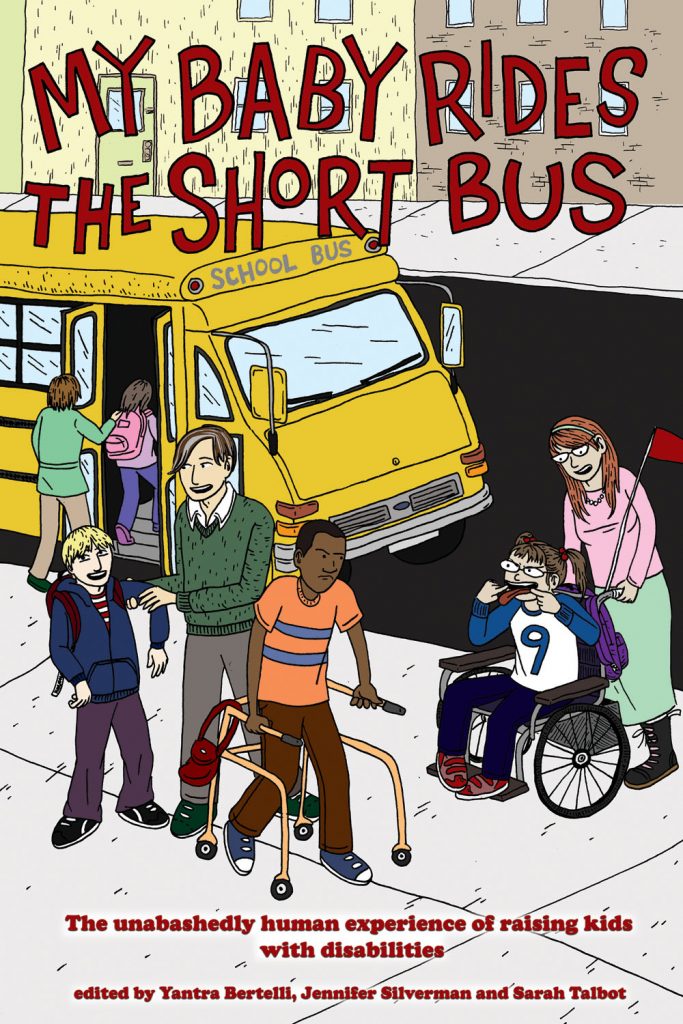

My Baby Rides the Short Bus is an anthology of articles written by parents about their firsthand experiences of raising children with disabilities. In addition to their common identity as parents of disabled children, the contributors also share another trait: all of them find themselves outside of the mainstream by virtue of identity or political perspective. Together the articles make up a lively collection of authentic voices that speak to the joys and challenges of being marginalized and/or subcultural parents raising special-needs children.

Many of the authors write about how their non-mainstream identities have affected their experience of raising special-needs children. Thida Cornes writes about how she learned to work within the constraints of her own disability, dystonia (a physical disability that causes muscular spasms), to take care of her son, who has been diagnosed with cerebral palsy. A lesbian minister, Maria June writes about becoming, at age twenty-three, the foster mom of a fifteen-year-old with special needs. Amber E. Taylor, a self-described “black biracial dyke with head-to-toe visible tattoos and a bald head” and an adoptive parent of a son with Down syndrome, writes about the backlash she receives from biological parents of disabled children who think she shouldn’t attend support group meetings because she “chose” to parent a special child.

The authors also write about the process of navigating the many institutions ostensibly set up to help special-needs children, but which often end up sidelining them. Several authors write about the experience of diagnosis: the behavioral testing milieu in which young children, separated from parents and subjected to unfamiliar conditions, unsurprisingly fail to show their full range of abilities, and then are slapped with labels that sometimes sound more like death sentences. Authors who spend 24/7 with their children write about the experience of not being believed by “specialists” about their children’s abilities and needs, or being subtly blamed for their children’s disabilities. Expressing the frustration felt by many of the authors, Kerry Cohen writes, “Unless I hate the things that make [my son] different from other children, I will always be a wayward mother.”

But not all the stories are about frustration and tragedy—many of the authors write about the creative and energetic ways they have found to help their children thrive, often in direct opposition to the institutions that are set up to “help.” Karen Wang and Heather Newman write about “unschooling”—creating stimulating and safe learning spaces at home, tailored specifically to their children’s particular needs—while Shannon Des Roches Rosa tells how she co-founded a special education PTA that helps parents of children with disabilities advocate for their children in the local public school system.

As so many of us know from personal experience, it can be very difficult to be part of multiple marginalized communities. As one of the authors, Andrea Winninghoff, laments, “In a community of parents with deaf kids, I will always be the single, young, gay mom. Among gay parents, I will always be the one with the deaf kid that they can’t speak to.” While there are many books available on parenting special-needs children, very few of those books offer an explicitly political analysis of the rights of special-needs families and of the systems that do or don’t serve them, and very few of those books acknowledge the experiences of parents who are out of the mainstream, whether due to race, class, gender identity or sexual orientation, disability, political beliefs, or lifestyle. Frank, engaging, and broad-ranging, My Baby Rides the Short Bus is a rare and precious treasury of these too-often invisible stories.

Back to Jennifer Silverman’s page | Back to Sarah Talbot page | Back to Yantra Bertelli’s page