By Ron Jacobs

Counterpoints

Most people seem to think that the saying “A picture is worth a thousand words” originated with Confucius, Ben Franklin or some other sage. In fact, it is actually attributed to an advertising man named Fred R. Barnard. Apparently, Barnard introduced the phrase in an article in the advertising journal Printers Ink discussing the merits of pasting advertising banners on the sides of streetcars in the early twentieth century. He suggested that using images in addition to text would reach more potential consumers. It’s quite fair to say that, despite its commercial intent, the phrase is not only true, but seems older and more profound than its origins as an advertising hook.

Photography is an art. Journalism is the description of places and events. Sometimes it feigns objectivity, sometimes not. The best photojournalism is both. Photography stops time. It enshrines history, but does not necessarily entomb it. Good photojournalism tells its story with few or no words. Great photojournalism, like great journalism, not only tells its story, it does so through the eyes of the person telling the story. In other words, such photos can, like great journalism, provoke the viewer to take action and join others in addressing the issues portrayed.

Orin Langelle is such a photographer. A longtime activist and organizer, Langelle’s photos have appeared in news organs, exhibits and elsewhere around the world. Several of them are now included in his new book titled Portraits of Struggle: Photos from 1972-2023 North and South America, Europe, Africa, Australia, Asia. These photos capture women and men going about their daily work and they capture them in direct struggle with forces of repression from Bolivia to California; Washington, DC and Tasmania; Brazil and Germany. The black and white portrait of Zapatista comandante Tacho appears on the front cover of the text, a radical and provocative indication of the photographs that fill the book’s pages.

As I noted earlier, photography stops time. All too often, this freezing of time removes the subject of the photograph from its place in history. The people captured within the photographic frame—the camera’s viewfinder—become an inanimate object, without agency or hope of change. The document becomes a trap. The soldier is always kissing the woman in Times Square and the US Vietnam veterans against the war are always tossing their ill-begotten medals over the fence. Hardly anyone viewing the image asks if the woman wanted that soldier to kiss her. The US troops are rarely considered as much more than totems, their importance as warriors turning against war minimized. The point of view of the photographer is diminished over time; if it was ever obvious in the first place.

With his photographs in Portraits of Struggle, Langelle refuses to let the moments he captures exist out of time, as if in some limbo of history where things might seem to just happen; without context, without politics and without meaning. The photos of protests against capitalist globalization place the viewer inside the photographer’s frame. The tear gas and the exhilaration envelop our senses and we are reminded of the political dynamics involved; exploitation and super-exploitation, challenges to corporate arrogance and murder captured in the struggle. The daily resistance to domination and capital’s disregard for humanity written on the faces in every photograph in the book.

As I have attempted to elucidate in my discussion of Orin Langelle’s book, still photography can be anything but still. Naturally, cinema is by definition a series of moving images. Often fiction, cinema can also be photojournalism. Like its parent the still photograph, the best documentary films place the viewer behind the filmographer’s eyes, seeing what they see while considering their interpretation as primary. Unfortunately, the modern film industry provides little to no space for radical and revolutionary film-making. The control of the studios by capital uninterested in progress and very interested in profit has made leftist cinema more of a rarity than ever before. At the same time, the profligacy of streaming services has made it possible for the viewer with determination and time to see many such films made in the past, fictional and otherwise.

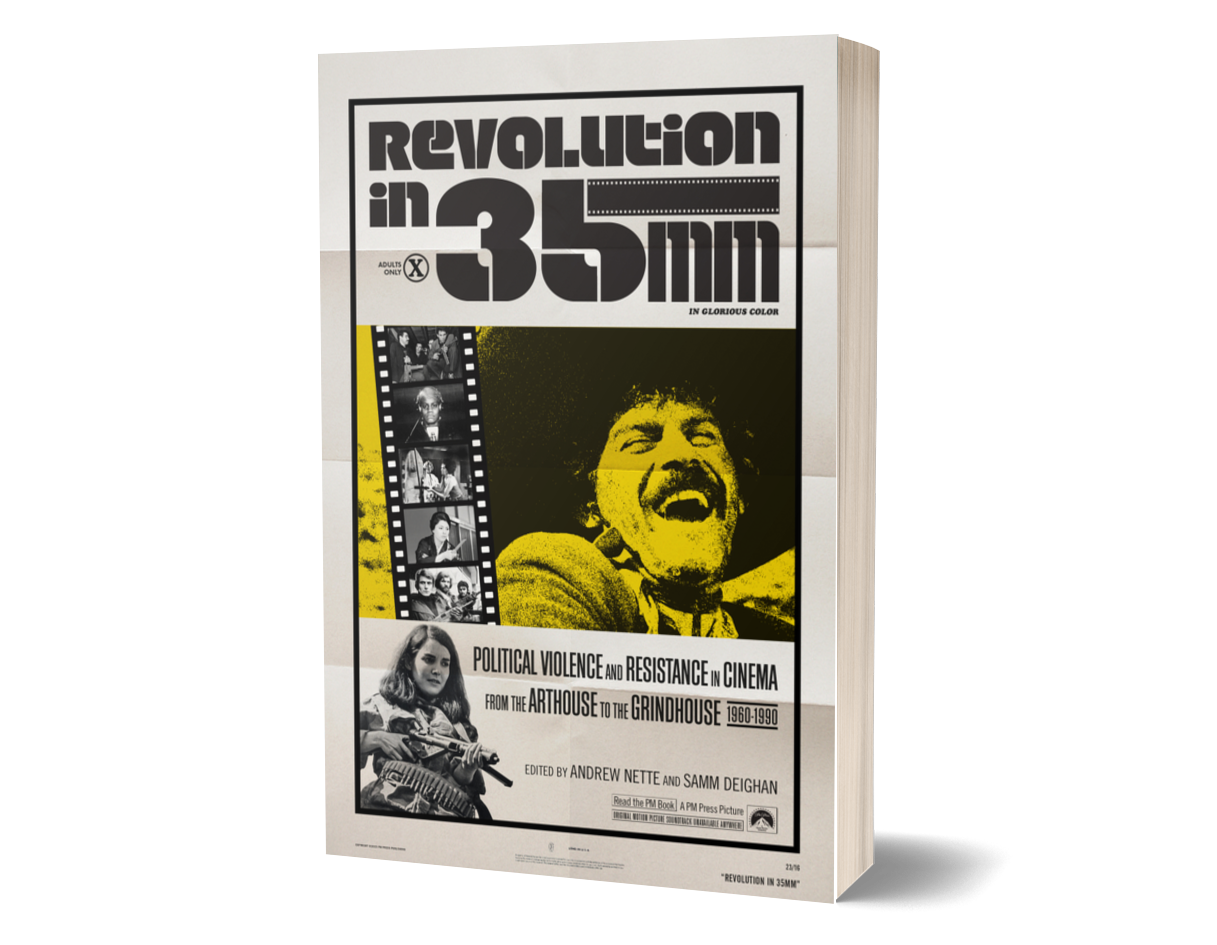

A recent book titled Revolution in 35mm: Political Violence and Resistance in Cinema from the Arthouse to the Grindhouse, 1960–1990 provides an excellent introduction to this genre. The period covered is arguably the genre’s heyday. As a person who rarely goes to movie theaters any more, but was an avid attendee in the 1970s and early 1980s, I can say Revolution in 35mm fulfills its function as a film guide considerably better than Rotten Tomatoes. As the title indicates, the films reviewed include many that might not be considered explicitly political, but are considered politically because of the director and writers involved or because the films are considered metaphorically. The editors Andrew Nette and Samm Deighan have curated a collection of reviews from fourteen film and cultural critics more or less from the Left, attractively arranging the reviews thematically and somewhat chronologically. Photos from the films being discussed are strategically placed in and around the text; full page photos of film advertising posters draw the reader to the text, ideally provoking them to write down the titles of the films being discussed. At least that’s how I read this book.

Films from Italy portraying the Years of Tension in terms of gangster and cops are presented and discussed. So are several films about the Bundesruplik Deutschland’s Red Army Faction. An in-depth discussion of director Costas-Gavra’s masterwork Z includes responses to the film’s success and its fictionalization of certain specifics. The Strawberry Statement—a fictionalized version of the 1968 Columbia uprising—gets reviewed and so does Zabriskie Point, a fantastical consideration of the fall of the United States directed by another foreign director Michelangelo Antonioni. Films from various nations on the African continent and Japanese cinema join this collection of films from around the world.

A friend of mine Robert Niemi taught film, US fiction and American Studies at St. Michael’s College in Vermont for years before he passed in 2022. Hanging out with him was always a learning experience in terms of cinema. In our conversations I discovered films I had never heard about and hardly heard about. His insights regarding films I had already seen sometime in my past expanded my understanding of the individual films we talked about and cinema in general. Ourfavorite US director was Robert Altman. In fact, Niemi wrote what I consider to be the ultimate critical work on Altman’s films, The Cinema of Robert Altman: Hollywood Maverick. Before he died, he had been involved in a film project with documentary filmmaker Denis Mueller that was to be a consideration of the US novelist Russell Banks. (The film awaits more funding, I believe). Robert would have loved Revolutions in 35mm, as a film buff and a critic. I like to think he would have found as many of the book’s films as he could and then watched them all. One could find many less interesting ways to spend one’s time.

Ron Jacobs is the author of several books, including Daydream Sunset: Sixties Counterculture in the Seventies published by CounterPunch Books. His latest book, titled Nowhere Land: Journeys Through a Broken Nation, is now available. He lives in Vermont. He can be reached at: [email protected]