By Samm Deighan and Andrew Nette

CultureMag

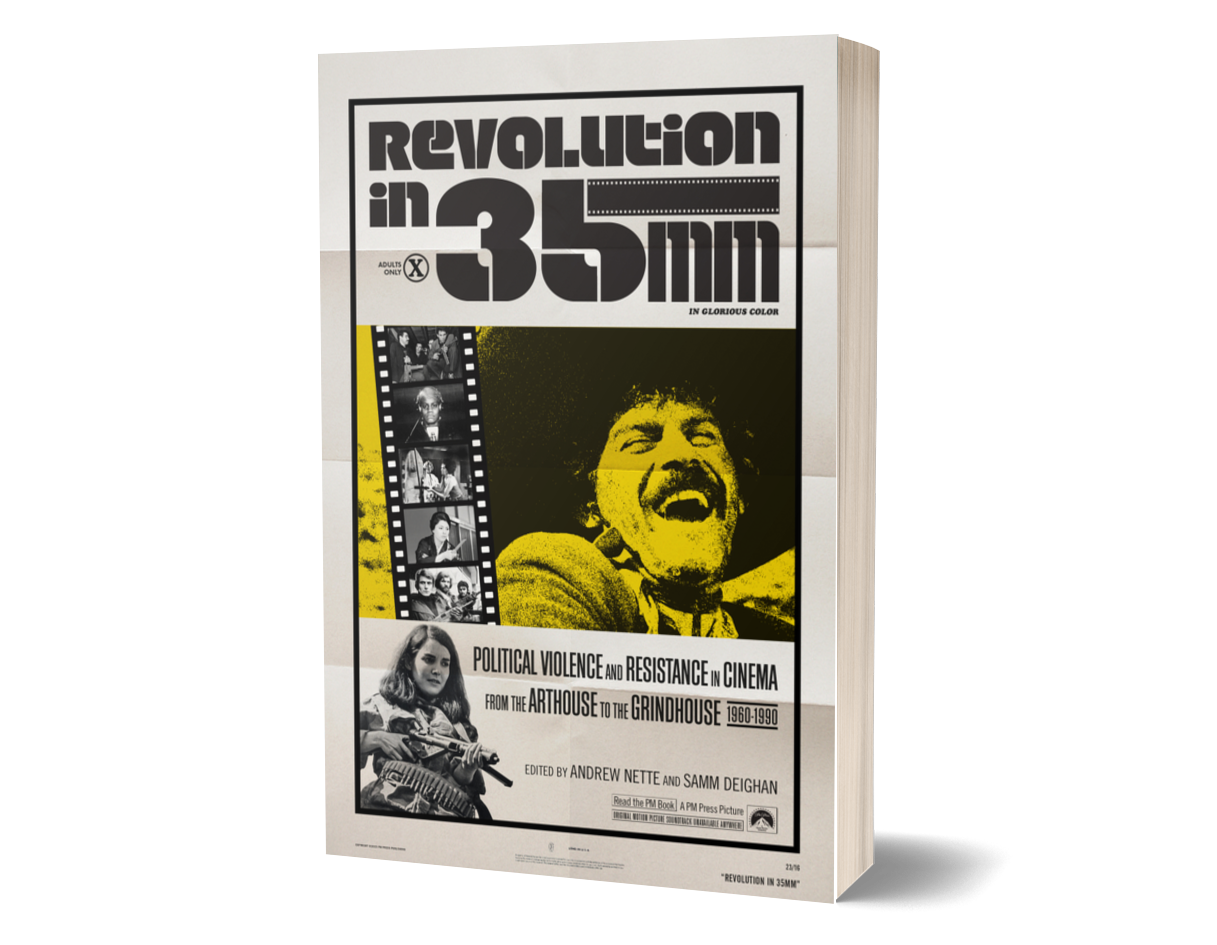

Andrew Nette/ Samm Deighan: Revolution in 35mm: Political Violence and Resistance in Cinema from the Arthouse to the Grindhouse, 1960–1990. PM Press, Binghamton, New York 2024. Large format paperback, 386 pages, over 200 illustrations, USD 29,95.

This richly illustrated book, just fresh off the press, examines how political violence and resistance was represented in arthouse and cult films from 1960 to 1990. This historical period spans the Algerian war of independence and the early wave of postcolonial struggles that reshaped the Global South, through the collapse of Soviet Communism in the late 1980s. It focuses on films related to the rise of protest movements by students, workers, and leftist groups, as well as broader countercultural movements, Black Power, the rise of feminism, and so on.

The book also includes films that explore the splinter groups that engaged in violent, urban guerrilla struggles throughout the 1970s and 1980s, as the promise of widespread radical social transformation failed to materialize: the Weathermen and the Black Liberation Army in the United States, the Red Army Faction in West Germany and Japan, and Italy’s Red Brigades. Many of these movements were deeply connected to culture, including cinema, and they expressed their values through it. Twelve authors, including film critics and academics, deliver a diverse examination of how filmmakers around the world reacted to the political violence and resistance movements of the period and how this was expressed on screen. This includes looking at the production, distribution, and screening of these films, audience and critical reaction, the attempted censorship or suppression of much of this work, and how directors and producers eluded these restrictions.

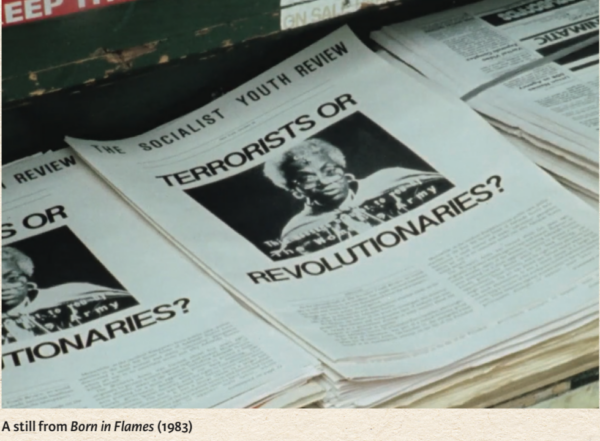

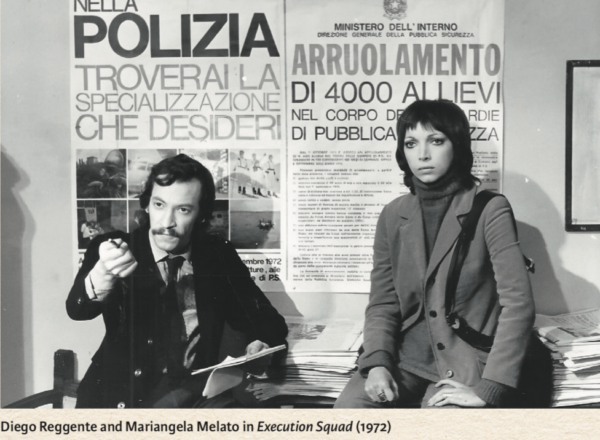

Including over two hundred illustrations, the book examines filmmaking movements like the French, Japanese, German, and Yugoslavian New Waves; subgenres like spaghetti westerns, Italian poliziotteschi, Blaxploitation, and mondo movies; and films that reflect the values of specific movements, including feminists, Vietnam War protesters, and Black militants. The work of influential and well-known political filmmakers such as Costa-Gavras, Gillo Pontecorvo, and Glauber Rocha is examined alongside grindhouse cinema and lesser-known titles by a host of all-but-forgotten filmmakers, including many from the Global South that deserve to be rediscovered.

With friendly permission from the authors – based in Melbourne and in New York City – and the publisher we present the introduction by editors Samm Deighan and Andrew Nette. Here it is:

** **

A Cinema of Resistance on the Margins

Political violence is generally described as violence perpetrated to achieve political goals: war at home or abroad, military coups, genocide, a state’s repression of its own people, terrorism, guerrilla warfare, kidnappings and assassinations, violent protests, and organized crime. It also includes violence that occurs because of the ideological oppression associated with racism, sexism, and classism. Although it has always been part of human history and took on particular importance in the modern world with the French Revolution in the 1790s (which birthed the term terrorism), political violence was enacted on an unimaginable scale in the twentieth century, with World War I and World War II as defining global events. World War II in particular is often described as the key historical event of the twentieth century, one that irrevocably shaped modern life. On a cultural level, this especially makes sense because narratives about the war often provide a clear hero (the Allied powers, democracy, the ideal of freedom) and an obvious villain (the Axis powers, fascism, the horrors of genocide).

The decade that followed World War II was marked by a series of murkier, more nebulous conflicts: the Cold War, which had been brewing since the surrender of Nazi Germany in 1945 but is viewed as officially starting with the exclusion of pro-Soviet Communist parties from government in Italy and France in 1947; the Korean War (1950–53); the Cuban Revolution (1953–59); and the Algerian War (1954–62), which became symbolic of the struggle for independence many countries faced around the world. In much the same way that Vietnam defined the American left in the second half of the ’60s and the first half of the ’70s, the war for independence in Algeria was a dominant focus for the European left in the 1950s. It also helped to inspire a series of wars fought to achieve freedom from colonialist states like France, England, and Portugal, which would eventually lead to dozens of African countries achieving independence. This must be considered alongside the near-global outrage over the Vietnam War and the West’s worldwide campaign to erad- icate communism, which helped birth, among other developments, a series of disastrous military dictatorships in Latin America and Africa. These coincided with fascist dictatorships in places like Spain and Greece, Stalinist totalitarianism in the Soviet Union and its satellite states, and so on.

In the West, various social movements arose in response to these struggles, particularly in the ’60s and ’70s, resulting in wide-scale protests, primarily from students, blue-collar workers, leftist groups, and those linked to the civil rights, Black Power, and feminist movements. In addition to challenging dominant economic and political structures, some of these movements sought to engender broader cultural and social transformation. Dissatisfied with the slow pace of change, others broke away and formed urban guerrilla groups, inspired primarily by national liberation movements in the Global South and also by each other: the Red Army Faction of Germany and Japan; organizations like the Black Liberation Army, Symbionese Liberation Army, and the Weathermen, to name a few in the US; the Red Brigades in Italy; and the Provisional Irish Republican Army, among others. While these movements developed as a response to specific local and cultural concerns, they were also connected on a global scale. Not only were there parallels between radical groups around the world, they also became intertwined in a more literal way. As Martin Klimke writes in The Other Alliance: Student Protest in West Germany and the United States in the Global Sixties (2011), “Whether we describe sixties’ protest as a revolution in the world-system, a global revolutionary movement or a conglomerate of national movements with local variants but common characteristics, its transnational dimension was one of its crucial motors.”

Many of these protest movements were also connected with and expressed their values through art, literature, popular culture, and, of course, cinema. Our book Revolution in 35mm: Political Violence and Resistance in Cinema from the Arthouse to the Grindhouse, 1960–1990 is an examination of how filmmakers around the world reacted to the political violence and resistance movements of the period and how this was expressed on-screen, primarily in arthouse and cult films. There is not the space here to engage in a debate about the precise meaning of “arthouse” and “cult” film, except to acknowledge that both terms are contested and slippery. At its most basic, “arthouse cinema” refers to the nebulous body of films — often independent productions for smaller markets— created as art, rather than as commercial products; arthouse films are often deliberately made as a counterpoint to Hollywood. “Exploitation films” refer to a body of low-budget films that emerged in the mid-’60s that rely on graphic representations of violence and sex for their audience appeal and were often shown in so-called lower-class inner-city cinemas, sometimes referred to as grindhouses. Our emphasis on these two strands of cinema, rather than the mainstream film market, is because both provided more freedom of expression for filmmakers.

The focus of this book is on films made during the decades between the Algerian War in the late ’50s and the fall of the Soviet Union in the early ’90s. While there are certainly films made before and after that period that depict political violence and resistance, the films made in this rough thirty-year span have a certain unique cohesion and interconnectedness. Many emerged from and reflected a historical era often referred to as the “long Sixties,” a shorthand term for a period of rapid change that began in the late ’50s and continued well into the ’70s. We have also chosen to include cinema from the ’80s, which depicts a continuation of key issues and themes: the trans- formation of the global order, in particular the gradual dissolution of the Soviet Union and its notion of “actually existing socialism,” which birthed and continued to influence much of the politics of the ’80s; the decline of a certain type of solidarity politics and anti-imperialist and anticolonial movements in the Global South, a development related to the political degeneration of many of the liberation movements they were aligned to and, in cases where they came to power, the governments they formed; and the shift from industrial to finance capitalism, which had major impacts worldwide, including on cinema.

Clearly, 1968 is especially significant as a radical watershed of sorts that had been many years in the making and that would continue to reverberate well into the ’80s. This is best exemplified by literary critic and philosopher Fredric Jameson’s notion of the “long 1968.” The political, social, philosophical, and cultural ripples of 1968 were particularly influential for cinema. Christos Tsiolkas’s essay in this book on Costa-Gavras’s 1969 political thriller Z discusses how its reception was framed by the post-’68 call on filmmakers to take a political position, “to commit to the popular (and therefore capitalist) or to the experimental (and therefore radical), [which] had already convulsed much of international cinema.” Academic Sarah Hamblin notes in an article in the 2019 issue of Cultural Politics how the political maelstrom of 1968 also led many filmmakers to reject the more “authoritarian model in which the film maker is positioned as the master who aims to impart specific wisdom to the unaware audience.”

This shift, which was obviously influenced by numerous factors, is touched on in several of the pieces in this book, from Latin America’s “new cinema” movement of the 1960s and 1970s to the evolution of European directors like Jean-Luc Godard. In European Cinema: Face to Face with Hollywood (2004), German film historian Thomas Elsaesser discusses how 1968 “coincides with a period of stagnation and structural changes in Hollywood which led to larger-scale mergers, takeover bids and boardroom struggles for control of the industry’s assets.” Among many changes, this led to Hollywood’s attempt to attract younger audiences with films depicting the campus revolt that was sweeping the US, and much of the West, and the violence associated with it. Some of these efforts are explored by Kimberly Lindbergs in her piece on campus revolt cinema, as well as by Michael A. Gonzales in his essay on the 1973 film The Spook Who Sat by the Door, once little known but now considered an important revolutionary film from the period. In reference to the earlier point about the porous nature of film categories, these movies arguably straddle the divide between arthouse, grindhouse, and mainstream cinema.

Revolution in 35mm does not seek to be a conclusive account of the political period concerned. The essays in this book—both full chapters and shorter “outtake” essays — do seek to explore the films of politically active, for the most part overtly left-wing filmmakers from a wide range of countries, including the Global South, who were depicting and/or responding to real-life political violence in their work during these decades. These depictions include overt political violence (revolution, assassinations, guerrilla warfare, riots, and state-sanctioned kidnapping, disappearance, and torture) as well as violence that is not overtly political but represents historical political symbolism in its subtext (like the Italian poliziotteschi crime films and the “Zapata” spaghetti westerns, bank-heist movies in West Germany, Bollywood gangster cinema, and so on).

Within the scope of one volume, it is of course impossible to cover every film made from 1960 to 1990 that includes depictions of political violence. We have chosen to focus on certain subjects that heavily feature this theme: key filmmaking movements like the French, Japanese, German, and Yugoslavian New Waves; subgenres like spaghetti westerns, Italian crime films, Blaxploitation, and mondo movies; groups of films that reflect beliefs held by specific movements like feminists or Vietnam War protesters; and the work of particularly influential political filmmakers such as Costa-Gavras and Gillo Pontecorvo. Likewise, in the interest of focus, this book does not include popular mainstream films, made-for-TV movies, or more straight- forward, conventional documentaries.

That there are large gaps in this book’s coverage is due to many issues. A lack of films featuring political violence is evident from certain regions, because of reasons such as censorship or political repression. With that said, filmmakers living under dictatorships often developed their own strategies for making, distributing, and screening their work, sometimes with lethal consequences for those involved. Evidence of this can be found in essays discussing cinema from the ’60s and ’70s in Argentina, Bolivia, and Yugoslavia, for example. Another obstacle was locating and viewing some films. This is a particular problem in relation to the work of directors from many regions within the Global South, but as many essays in this book address, it is also a much broader problem for directors with radical political views regardless of geographical location: American filmmaker Robert Kramer is a notable example, as his films from the ’60s and early ’70s are incredibly difficult to track down.

This book aims to be something other than an encyclopedia of non-mainstream films concerned with political violence and resistance. It seeks to show how filmmakers outside the mainstream, from different countries and often different decades, and generally working in different cinematic genres, are in conversation with one another and often share many similarities. Examining these films as a collective body also allows for a broader view of their filmmakers’ shared explorations of radical politics, political violence, and modes of resistance. Many of the films discussed in this book raise questions and instigate discussions about the aims of political violence and its effectiveness, still relevant at a time when such violence is on the rise again globally: war in Eastern Europe, protests and executions in Iran, a wave of right-wing violence and an attempted extremist overthrow of the government in the United States, the persecution of Palestinians by the Israeli state — the list goes on. By comparing what is a largely marginal cinema, from the arthouse to the grindhouse, we are hoping to expose a more complex understanding of certain types of cinema, like low-budget genre fare that is often dismissed from more serious conversations of cinema as an art form. Finally, we hope to highlight underseen films and the important work of neglected filmmakers, many of whom made incredible sacrifices — including their lives in some cases — to contribute culturally to the ongoing global fight for radical freedom.