A History of the Alt-Right

I love a good heist story. You know the ones, our heroes are planning a seemingly impossible task. They are the good guys, forced to operate outside the law for unjust reasons. The team is always composed of specialists: you have the getaway driver, you have the cat burgler, you have the muscle, you have the confidence grifter, you might have someone working on the inside, feeding them inside information. Nowadays, you also have the hacker who can break inside any computer system. They are all the best of the best, and despite their tremendous odds, they emerge victorious at the end of the tale. One of my favorite shows was Leverage (and its continuation, Leverage: Redemption) which told such a story every week. It was all rip-roaring good fun.

One of the showrunners for Leverage was John Rogers who has a very successful career in show biz, and is the author of this famous quotation:

Here are two novels that can change a bookish fourteen-year old’s life: The Lord of the Rings and Atlas Shrugged. One is a childish fantasy that often engenders a lifelong obsession with its unbelievable heroes, leading to an emotionally stunted, socially crippled adulthood, unable to deal with the real world. The other, of course, involves orcs.

This brings us to the amazing book, Raymond B. Craib‘s Adventure Capitalism,which is like a heist story. Except for the heist crew being hyper-competent adventurers, the crew is the Three Stooges entranced by Ayn Rand. Instead of pretending to hurt each other, Larry, Moe, and Curly hurt other people. But, like the Stooges, Craib’s crew utterly failed in what they attempted.

The center of Adventure Capitalism is Michael Oliver, a Lithuanian Jew who was the only member of his family to survive the Holocaust and came to the United States. Like many refugee Jews of his generation, Oliver was attuned to the dangers of totalitarian governance. Unlike most of his cohort, he did nothing to ensure “it can’t happen here,” Oliver chose a different path. Oliver was “worried that his adopted country in the 1960s teetered on the brink of totalitarianism. He thus saw exit as the most viable way to survive and thrive, and he spent much of the decade of the 1970s traversing the globe in the hopes of establishing a new country.” Oliver and company’s attempts to create a libertarian paradise. During the early 1970s, Oliver et al. attempted to dredge an island in the Southern Pacific region. The attempt was quickly terminated by Tonga, who understood the reef upon which the “island” was to be erected as their own. A second effort, aided by well-armed mercenaries, failed in the Abaco region of Bahamas. Yet a third, this time in what is now Vanuatu, failed again, despite backing from libertarians such as John Hospers and the US Libertarian party and buckets of Oliver’s money. Such efforts continue today under the leadership of folks such as Milton Friedman’s grandson in the seasteading movement. Craib relates this with extensive archival research and a storyteller’s knack for writing page-turning prose.

For me, Adventure Capitalism underscores the moral bankruptcy of libertarian exiteers. Randian libertarians, Craib argues, “seem indifferent to the general public and express disdain for democratic politics.” Community action, voting, organizing, advocating, and efforts to improve society, none of which were for Oliver; rather, he adopted Brave Sir Robin’s strategy of “Run Away! Run Away! Craib gives no indication that Oliver was concerned about those he left behind in the United States being crushed by the hobnailed boot of totalitarianism. Craib notes that Oliver’s effort to establish a libertarian paradise was a “moral experiment.” Oliver’s moral message was clear: The proper response to the rise of totalitarianism, such as that in Germany in the 1920s, was to have enough money to abandon those fighting against the Nazis to the concentration camps. Present-day libertarians think that “what happened to Oliver’s family during World War II” means that any “Quests to evade such ends are worth respectful consideration.” In my mind, this shows the immorality at the heart of libertarianism: better to “evade” Nazi governance than to prevent Nazi governance. What about those who lack the resources to exit? “Let the looters die” seems to be the libertarian answer. Reaching this conclusion seems inevitable after any “respectful consideration” of libertarian exit strategies.

Since Oliver failed in his attempts to create his utopia, we are left to wonder what life in such a place would be like. Other than vague promises about “freedom” libertarian exiteers are very vague about life in these supposed utopias. Rand never let us lesser beings inside Galt’s Gulch for example. Atlas Shrugged is, of course, fiction. For a better fictional account of such a libertarian society, I highly recommend Naomi Kritzer‘s Liberty’s Daughter. Read it in conjunction with Quinn Slobodian‘s Crack-Up Capitalism: Market Radicals and the Dream of a World Without Democracy to get more information about these capitalist “paradises” than you’ll ever get from the libertarian exiteers.

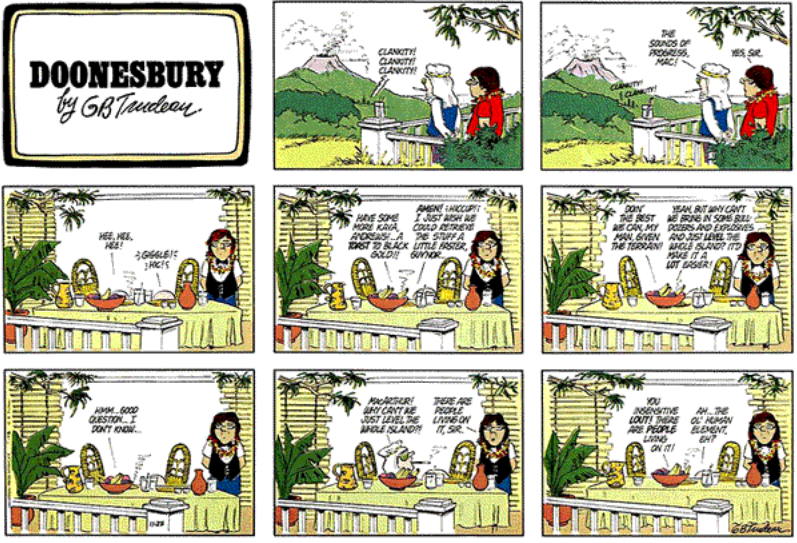

Craib details indigenous understandings of land, ownership, and kinship that cannot be reduced to the Lockean understanding of “property rights” that libertarians claim to be universal. The human experience is richer than that, and in, as Craig’s subtitle has it, the “era of decolonization’ the formerly colonized were boldy asserting their alternative understanding of humanity’s relationship to the planet. Part of the problem the exiteers face is that their idea of unoccupied land just waiting for them to “mix their labor” with to make it their own private property has always been a lie. People are living on it. Those people have their own ideas about their relationship with land, which might not match those of libertarians. Hence, Oliver’s need to hire mercenary soldiers to create his private society based on the “non-aggression” principle of libertarians. That anyone finds the libertarian exiteers moral actors seems beyond belief to me. Go read Adventure Capitalism to see their moral bankruptcy.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.