By Hope Light, Wren Awry, and Shayontoni Rhea Ghosh

Riot and Roux

Jan 19, 2024

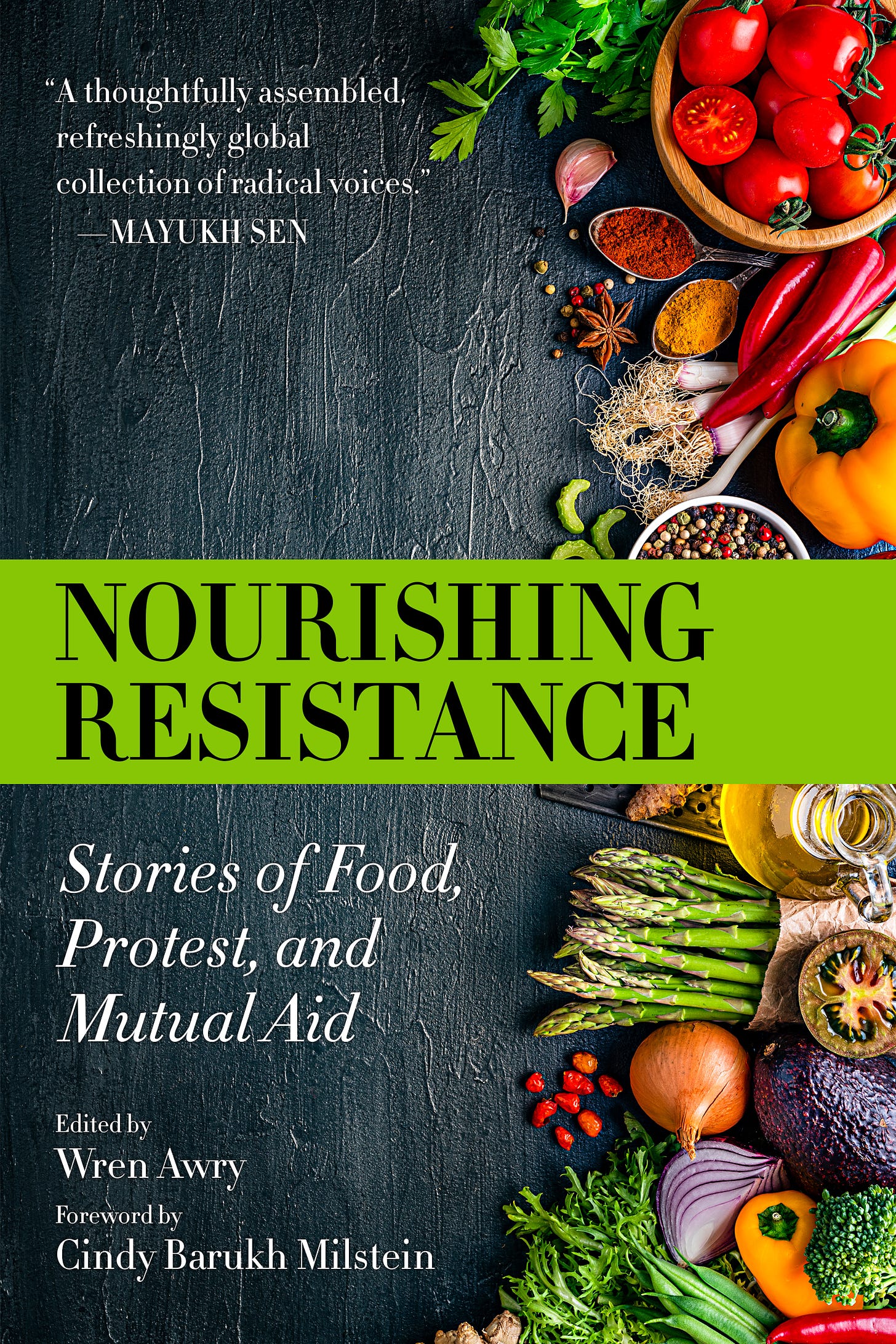

As those of us in the Northern Hemisphere settle into winter with the intensity of the ‘holiday season’ behind us, we wanted to remind folks that this season is meant for rest. Although we’re all too aware that not everyone has the luxury of taking an actual break, we encourage everyone to carve out restful moments. We’ve been spending our restful moments reading Nourishing Resistance: Stories of Food, Protest, and Mutual Aid, an anthology that argues that food is a central, intrinsic part of global struggles for autonomy and collective liberation, edited by Riot and Roux! contributor Wren Awry. With 23 pieces of varying lengths, it reads from beginning to end as a reminder that food and community are critical components for resistance, or if you’re short on time, you can open to a random essay as each stands on its own.

Wren and Nourishing Resistance contributor Shayontoni Rhea Ghosh have graciously provider the following exert for you to enjoy.

Riot and Roux! is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The Hearth of Revolution

By Shayontoni Rhea Ghosh

In the multipurpose living/dining/bedroom of my childhood home in Kolkata was a large wooden cabinet. It took up the entirety of one wall and housed the television, so a lot of our time was spent looking at it. Our clothes, my grandparents’ documents, and assorted knick-knacks were packed carefully in the dusty drawers. Right on top of the cabinet was a clunky, black radio. The radio was always on. Our days—languid, humid, and melancholic—were set to a constant supporting soundtrack.

Today, my mother sings in the kitchen all the time. We’re a territorial family and, while she will insist otherwise, Maa doesn’t like sharing space in her kitchen. I stand at the door and watch her make aloo posto, a beloved Bengali dish. The poppy seeds are left to soak overnight and ground with chilies to make a thick paste, which bathes cut potatoes and is cooked with nigella seeds, turmeric powder, and green chillies in mustard oil; served with steamed ghee rice. She chats about the dish while making it, regaling me with stories about how Bengali people would, and still do, eat plates of rice and aloo posto for lunch, and immediately treat themselves to a siesta.

My mother’s ancestral home on her mother’s side, in the Bikrampurjela of Dhaka, now-Bangladesh, was, in her own words, heaven-sized. A sprawling property surrounded by fruit orchards, ponds, and farmlands, the house was a testament to the strength and community-oriented practices of the Bengali people. The orchard, in particular, stands out.

Colonial India was made up of warzones of numerous kinds. We were fighting the state, fighting amongst ourselves, bargaining with the forces of nature. We were watching familiar institutions crumble to dust and trying to rebuild. We were singing to keep our spirits up, dancing to retain agency over our mortal vessels, and walking, blind-folded, into a future we could not begin to map out.

In the first half of the twentieth century, resistance in the forms of the Swadeshi movement; Gandhi’s fervent attempts at non-violence; and dissenting homebodies like young socialists, revolutionaries, political activists, and organizers were picking up steam. Skilled at dividing the community, the British government passed the Bengal Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1930and instructed all local police stations to be on high alert for criminals and revolutionaries in their jurisdictions. Unexplained curfews, arbitrary arrests, and surprise home raids followed. The results of these were nothing to write to the British about—some “freedom-oriented literature” and a few stragglers. The local police, then, took a page from the colonizer’s book and started considering divide-and-conquer strategies of their own. It was common for the police to pick up an innocent wage-earner or a landless farmer, torture them with verbal and physical abuse, and release them on the condition that they become an informant. For the person in captivity, between a rock and the hard place of corrupt bureaucracy, the semblance of a choice was not apparent. Additionally, the police started to bribe the poor with pocket change and the promises of a better life if they could come to them with any incriminating information about their employers.

The home in Bikrampur sheltered many dissidents from the Dhaka Anushilan Samiti, the local branch of the revolutionary Anushilan Samiti Movement. Armed with the gift of space and the cover of nature, my great-grandfather Priyanath Ghoshal started building shacks in the orchard. Protected from the snooping eye by towering trees, the shacks would store mountains of dried leaves and branches by day and house dissenters on the run by night. Local organizers would stop him on the streets or in the market to ask for help, and one time he was approached by the devastated mother of a young revolutionary. His wife, my great-grandmother Kusumkumari Devi, was the only one who knew about the goings-on in the orchards. Terrified of the consequences but driven by principle, young Kusumkumari Devi took to the kitchen with vigor.

In A Tale of Two Cities, Charles Dickens wrote about, “the vigorous tenacity of love, always so much stronger than hate.” Was it love, then, that made my young great-grandmother cook for scores of unknown men and young boys? Tenacity which allowed my great-grandfather to shelter these headstrong and fiercely intelligent revolutionaries for days on end, risking the lives of his family and property? Perhaps. Today, as I gain a deeper understanding of the work I am here to serve—facilitating healing spaces for groups and individuals, creating theater, and writing—I tap into this quality of what-feels-like-love.

Kusumkumari Devi’s kitchen was a space of devotion. Forced to cook for her guests by herself, and away from the hawk-like gaze of their regular cook, she would let the silkymasoor dalsimmer while preparing baby potatoes in cumin seeds and mustard oil. She and her husband would carry the food out in batches into the orchard during the dead of night and keep watch while the revolutionaries gratefully wolfed everything down. Wary of informants, the young men were forced to leave every hideout spot after a week, at the latest. On the eve of their departure, my great-grandmother set about doing what she did best, and scoured every market and every neighbor’s home until she was able to collect a few pieces of fish. After thoroughly cleaning the fish and slathering them in turmeric, salt, and mustard oil, she set about cooking a simple curry to go with the ghee rice. That night the freedom fighters, persecuted by the state and the police, slept content.

My mother’s father’s ancestral home was in Ramna, Dhaka. My great-grandfather Monoranjan Chowdhury was not planning to house dissidents from the nearby localities, but when the door of his humble home shook with knocks in the middle of the night, he sprung to action. His wife, Hemprabha Devi, was resting after a long day of housework and childcare and was perturbed at the midnight interruption. However, when a group of fearful young boys poured into their home, she knew what needed to be done. She took to the kitchen immediately and soaked all the leftover rice from the day’s meals in water. The next morning, when the sun’s rays smiled over their home, the young couple served their guests a meal of paantabhaat—the soaked rice, served with a dash of oil, chilies and some onions.

The following week was an exercise in self-restraint and generosity for my ancestors. I remain awed at the bravery they displayed in conversations with their neighbors: taking care never to reveal more than they should, always ensuring they weren’t seen with more groceries than a household of three would need. The local police stations had already started plastering notices on public walls, asking citizens to step forward with any information about suspicious activities and strangers appearing in the neighborhoods. The air was heavy with fear.

My mother’s father was four years old when the police barged into the house one night, demanding to know the whereabouts of a local youngster who was said to be helping the revolutionaries organize and find shelter. In the few seconds from the first knock on the door to the policemen entering the house, the dissidents had neatly packed themselves under the one bed of the house, holding their breath and tears. Monoranjan Chowdhury shook in fake consternation and held down the fort while his wife, with my grandfather on her lap, demanded her house be emptied of the swine.

My ancestors shouldered immense risks in service of their faith and convictions. The slightest shift in energy or a step out of line could mean a few annas worth of information, and more than a few deaths. Today, when I consider the legacy of my ancestors, I see how tightly I am bound to their convictions. Freedom from a fascist state, from spiritual and national terrorism. Freedom to dream, to thrive, and to hope for a softer tomorrow. I see the deep relevance of the kitchen as a gender-neutral and generative space of the home. A space of rebellion, communion, and awe.

Today, my mother protests as I elbow her out of the way and adamantly add a coat of olive oil to the potatoes. I grab the wooden spoon and stir the posto with determination. After spending a long time avoiding the kitchen and domestic duties, I am now opening up to the immense possibilities of creativity, collaboration, and freedom which emerge from a true connection with one’s home, one’s hearth. I feel the spirits of my great-grandmothers and grandmothers around me, watching with pride as I tighten my grip on the kadai and stir the chopped green chilies with the potatoes. My mother takes a minute to rest her feet as I start setting the table. Before the first bite, she closes her eyes and expresses gratitude for the food. Her face blossoms, and I experience a rush of indescribable emotion.

Our reverence practices ask us to dedicate food to our ancestors before eating. On some occasions, we prepare an entire plate which rests on the altar for a day. But, every day, we say their names in our minds before taking a bite. I remember my great-grandmothers—toiling over the fire, smoke in their eyes and hair, saris bunched up near their knees; my great-grandfathers—bargaining at the markets, breaking their backs in the fields and at the factories. I remember the nameless, faceless ancestors who risked their lives in defense of life itself. I take a breath to return to the moment, and with love in my heart for who I am and what I serve, I take a bite.

It’s always delicious.

Shayontoni Rhea Ghosh is a writer, theatre-maker and facilitator, living and working out of Hyderabad, India. She is passionate about building accessible infrastructure for community care and wellness with her space DOT.

Purchase Nourishing Resistance

Wren Awry is a writer, editor, and archivist whose work ranges from researching and writing about the role of food in labor strikes, mutual aid projects, and revolt to helping with community dinners at their local, collectively run social center. They’ve written about and presented on anarchist and anti-capitalist food history for publications and platforms, including GastroObscura, Living & Fighting, Cool People Who Did Cool Stuff, and Blind Field: A Journal of Cultural Inquiry.

Riot and Roux! is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.