By Ed Rampell

Covert Action Magazine

August 29, 2023

What If the Co-Author of The Communist Manifesto Would Have Become a Gumshoe?

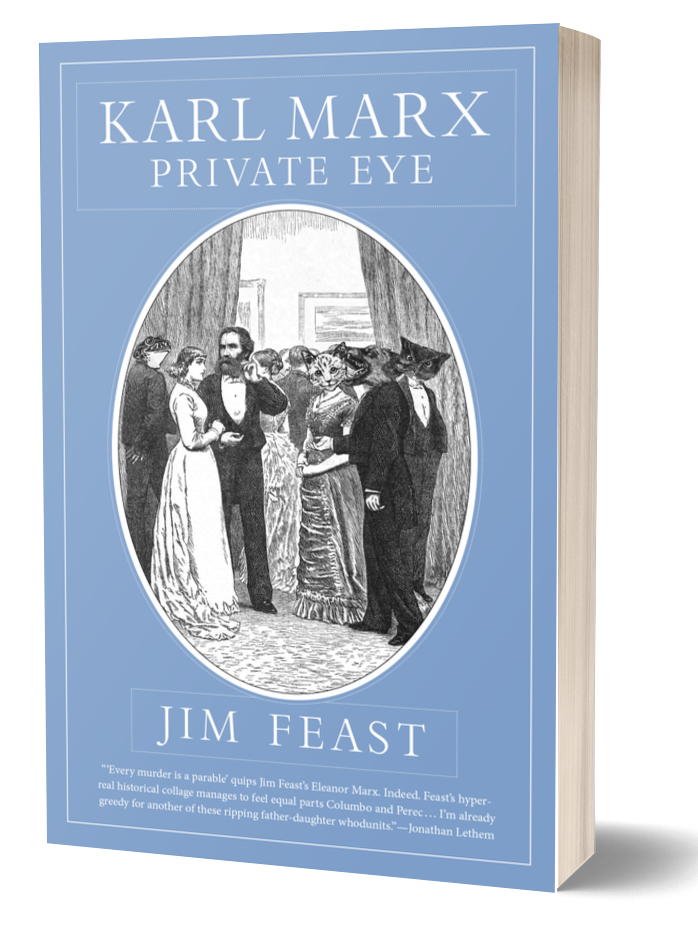

Novelist Jim Feast’s sly alternate history Karl Marx Private Eye (PM Press) somehow manages to bring Shakespeare, Sherlock Holmes, Karl Marx and his youngest daughter together at Karlsbad, Bohemia, in 1875.

The author may have chosen to set his whodunit at Karlsbad because, just as the detective Shaft “is a bad mother… (Shut your mouth),” Feast’s Karl is also a “bad” MF-er.

While Marx may not be, as Isaac Hayes sang in the 1971 Blaxploitation flick’s theme song, a “Black private dick” like Shaft, in Eye the co-author of The Communist Manifesto likewise tries to solve a series of crimes.

Marx has traveled to Karlsbad—Bohemia’s spa center, famed for its hot springs and resorts offering wellness treatments—seeking healing cures; among his health issues, Marx suffered from carbuncles. (In people’s historian Howard Zinn’s 1995 play Marx in Soho, the First International leader laments: “[T]ry working, try sitting and writing, with boils on your ass!… I discovered something miraculous – water… Cloths soaked in warm water.” And toward the end of his life, hoping to restore his well-being, Marx spent two months in sub-tropical Algeria in 1882.)

But, ironically, instead of cures amongst the thermal waters and fitness facilities, Marx stumbles upon a spate of murders most foul. The philosopher endeavors to crack the case, joined by his 20-year-old daughter Eleanor and a 16-year-old Sherlock Holmes, who is vacationing with his parents at the Tri Lilie Hotel (it still exists—see: https://www.trililie.cz/), which was established in 1793 and has hosted notables ranging from the poet Goethe to the reactionary diplomat Metternich and, more recently, playwright-cum-President Václav Havel.

The Holmeses stay at a discount rate in the luxury resort because Sherlock’s older brother, Mycroft, had worked with the Karlsbad-based Sergeant Hubner to prevent a crime that would have cost the Tri Lilie Hotel “a handsome sum.”

Like Marx, Eleanor and Sherlock, the muscular Hubner—“a German émigré” who wears “pith-helmet-like headgear… topped with a spike”—is hot on the trail of the assassins. (As for how the London-based Marxes could afford a health cure all the way in Bohemia in what is now the Czech Republic, my guess is that Friedrich Engels, son of a factory owner, probably footed the bill.)

Somehow, Feast deftly tosses the Bard of Stratford-upon-Avon into this combustible mix. No, the playwright, who died 250 years before the action in this novel takes place, does not make a personal appearance on the page. Instead, a rare Shakespeare First Folio, that initial collection of his stage works published in 1623, cleverly plays the role of what Alfred Hitchcock called the MacGuffin in this thriller.

Are the homicides connected through this Maltese Falcon-like plot device, with characters trying to find and sell this extremely valuable original edition? Or are thwarted romances to account for the procession of untimely deaths? Inquiring minds want to know. “The game is afoot!” as Holmes gleefully proclaimed in numerous short stories by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, whose style and vernacular Feast wittily emulates.

Feast puts Eye’s events into what Marx would call “historical context.” The Karlsbad crimes have been committed only four years after the Paris Commune, the modern world’s first socialist state, albeit short-lived. Marx rose to prominence championing the Paris Commune, hailing it in his 1871 Civil War in France: “History has no comparable example of such greatness. Its martyrs are enshrined forever in the great heart of the working class.”

The Paris Commune ignited a forerunner of the Red Scare; it was brutally crushed and some of those who escaped death and the ensuing repression fled France. As a champion of the Commune, suspicion was cast upon Marx, whom Hubner calls “the man behind the Paris Commune… the greatest renegade in the British empire.” (After the collapse of the 1848 workers’ uprisings on the Continent, the German-born exile relocated to London, where Marx is buried at Highgate Cemetery.)

In Karl Marx Private Eye, some of the outcast Communards live at Karlsbad. Are these French transplants behind the reign of terror in Bohemia? Or are members of another community of exiles, Serbian nationalists, carrying out the liquidations? (Forty years later, extremist Serbs would be blamed for triggering World War I by allegedly assassinating Archduke Ferdinand.)

Are any of these refugee activists shedding blood in order to seize the precious Shakespeare First Folio, sell it off and then use that treasure to finance their movement?

Karl, and the socialist’s apprentice, Eleanor, seek to catch the killer(s) by invoking the dialectical method. Using his powers of deduction, Sherlock takes an empirical approach, tracking down clues. Sergeant Hubner painstakingly pursues tried and true police procedures, wearing out the shoe leather, to get his man (or woman).

For almost a third of Eye, in order to protect his and Eleanor’s safety, Marx, the notorious revolutionary, hides his true identity, using the pseudonym “Dr. Arbuthnot.” I asked Feast what the significance of that particular name was, and via email the author replied: “In the book, the Marx family is constantly making literary allusions, which I think is plausible. Those who are not familiar with it might be surprised that Das Kapital is filled with quotations from Shakespeare.

“The name Arbuthnot comes from a poem by 18th century satirical poet Alexander Pope. In Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot, Pope, who was famous at the time, complains of people blaming his poetry for all kinds of negative influences. Remember—Marx’s writings were also blamed for any revolutionary outbreaks and for inspiring the Paris Commune, though they had little influence on the French workers.

A small group of workers belonging to the International, which Marx headed, were in Paris during the conflict, but they did nothing of significance. Even so, conservatives saw the International as behind everything that happened in the city.

“(Being from Chicago, I once looked at writings on the Chicago fire, which burned down most of the city and took place in October 1871, a few months after the Commune. Conservative journalists of the time said the fire was set by Internationalists who had come to Chicago after participating in the Paris Commune.)

“To get back to Pope, he writes, saying how his writing is blamed for inspiring many sins:

‘Arthur, whose giddy son neglects the laws,

Imputes to me and my damn’d works the cause:

Poor Cornus sees his frantic wife elope,

And curses wit, and poetry, and Pope.’”

Through the genre of detective fiction, Feast gives readers insight into his historical figures and their times. In Shaft’s theme song Isaac Hayes sang: “Who is the man that would risk his neck for a brother man? …Can you dig it?”

The same could apply to Marx, whom Eleanor wrote possessed “unbounded good-humor and unlimited sympathy. His kindness and patience were really sublime.” Marx may have been one of history’s greatest thinkers, but as Eleanor indicates, he was also compassionate, as Feast depicts in chapter 21, when he comforts the Serbian servant Swandra.

She is despondent about the murders; Marx shares coffee with her and “opened his arms so she could cry again using his shoulder…” He also humbly takes advice from the maid about the Serbs’ struggle for independence.

But for my money—or should I say “capital”?—the novel’s most interesting character is Eleanor. She is brilliant in her own right, a plucky heroine who defends the oppressed and literally risks life and limb to help solve the homicides.

No wonder that the fictional coming of age Sherlock, still an adolescent, is smitten by Eleanor, four years older. (Note: Feast appears to be a bit off on his timeline. Doyle is believed to have actually had his character born more or less the same year as Eleanor actually was in real life, which should have made them roughly the same age in Feast’s book. “Elementary, my dear Watson!” See: https://bakerstreet.fandom.com/wiki/Sherlock_Holmes.)

A passage written by Eleanor about her aged parents’ final days together that Erich Fromm quotes in his 1961 Marx’s Concept of Man has always stuck with me. “Moor [Marx’s nickname because of the swarthy complexion of the man who was of Jewish ancestry, and which Eleanor uses in Eye] got the better of his illness again. Never shall I forget the morning he felt himself strong enough to go into mother’s room. When they were together they were young again – she a young girl and he a loving youth, both on life’s threshold, not an old disease-ridden man and an old, dying woman parting from each other for life.”

According to PM Press: “Jim Feast helped found the action-oriented literary group the Unbearables, known for such events as a protest against the commodification of the Beats at NYU’s Kerouac Conference; annual readings with poets spread out across the Brooklyn Bridge; and a blindfold tour of the Whitney Museum.

In the early 1980s, he met and married Nhi Chung, author of Among the Boat People. She introduced him to Chinatown movie theaters, which played the path-breaking Hong Kong noir detective films of those days, giving him a new way to look at the murder mystery. Feast has worked for Fairchild Publications and later taught at Kingsborough Community College [in Brooklyn]. He edited seven books by Ralph Nader, including his three novels, and worked with Barney Rosset on his autobiography. He lives in Brooklyn, NY.”

His page-turner ends almost literally with a cliffhanger. Let’s hope Feast pens a sequel—after all, as Marx wrote in 1850, the revolution is permanent (https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1847/communist-league/1850-ad1.htm).

To read Karl Marx Private Eye see: https://pmpress.org/index.php?l=product_detail&p=1320.