recommended by Trevor Getz

Graphic narratives can be a great way to learn history but they need to be both good history and good comics. That’s a combination that can be hard to find. Trevor Getz, a professor of history at San Francisco State University, picks out his top comic books on African history.

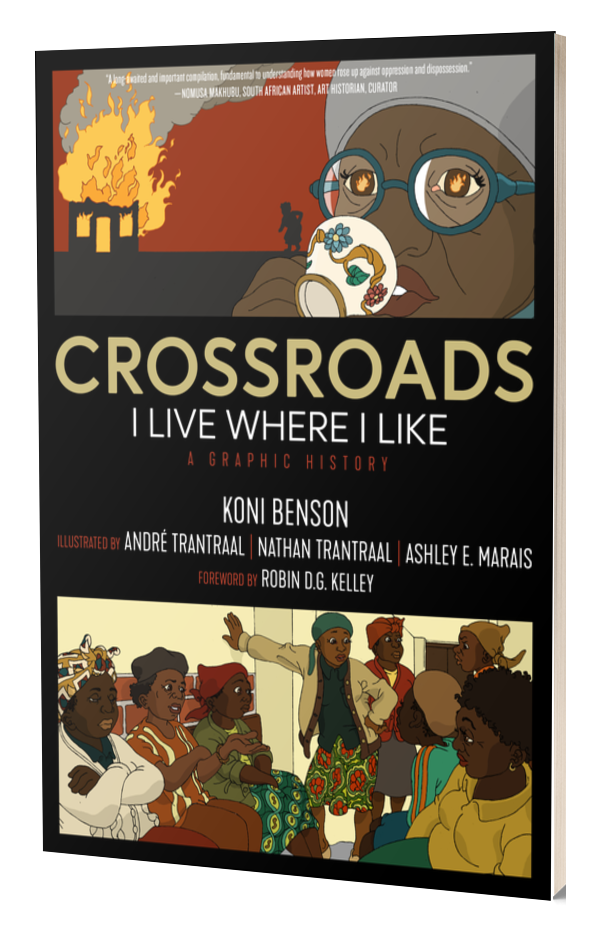

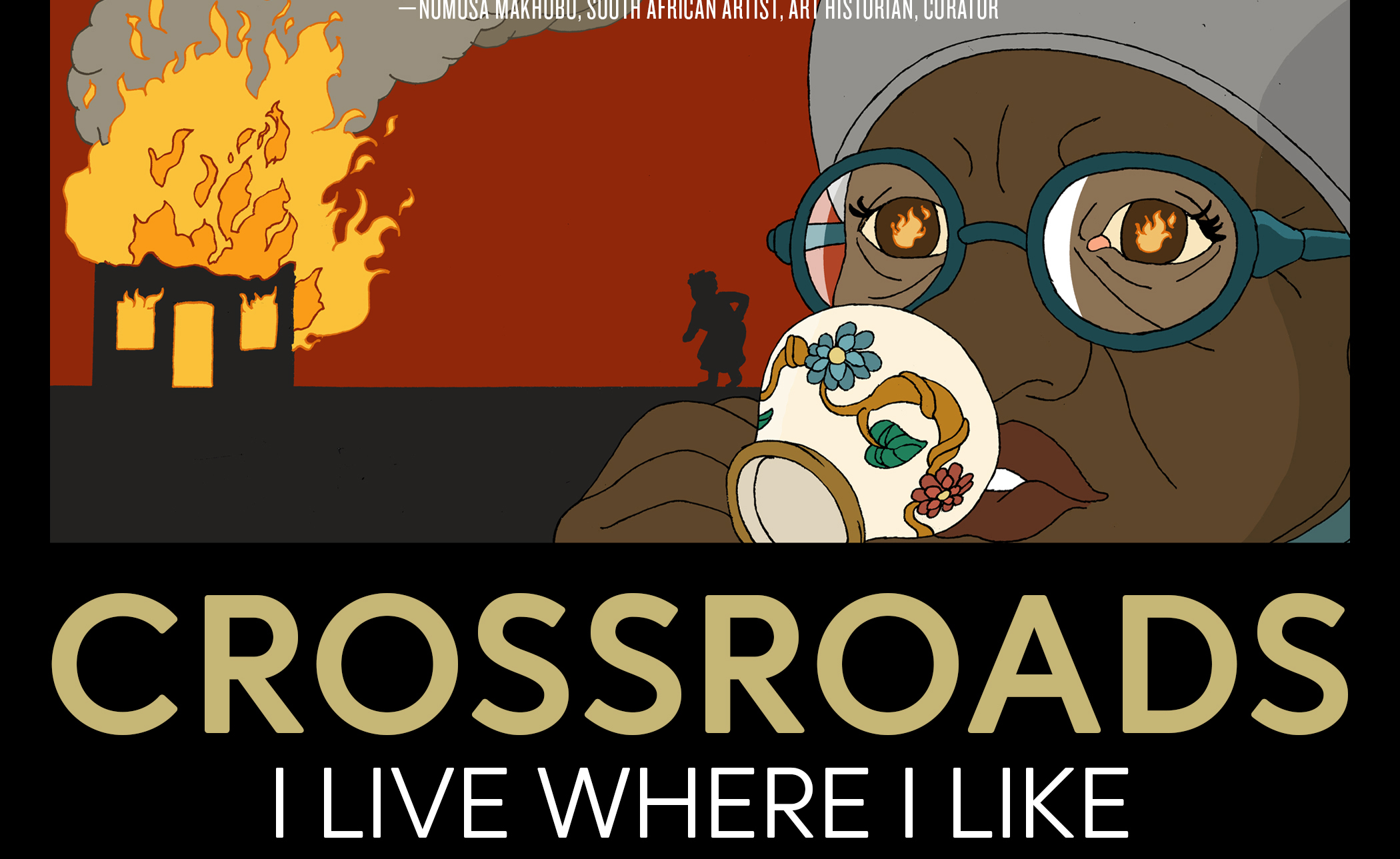

- Read 1 Crossroads: I Live Where I Like

Koni Benson, André & Nathan Trantraal (Illustrators), Ashley Marais (Illustrator) - Read 2 Aya

Marguerite Abouet and Clément Oubrerie (illustrator) - Read 3 All Rise: Resistance and Rebellion in South Africa

by Richard Conyngham (editor) - Read 4 Madame Livingstone: The Great War in the Congo

by Barly Baruti (illustrator), Christophe Cassiau-Haurie & Ivanka Hahnenberger (translator) - Read 5 Kariba

by Daniel Clarke, Daniel Snaddon & James Clarke

Before we get to the books you’ve recommended, could you give me your thoughts on graphic histories in general? As a historian, would you say comics can be a good way of learning history?

I think the bigger story here is that human society flattened what we consider to be serious work into one medium for a while, and we’re now in an exciting place where we recognize that there are lots of media. While there are some things that a text-only book can do best—including the delivery of densely packed information—other media, whether documentary video or comics, can be meaningful.

Comics have a couple of advantages. The first is that it is a medium native to many students. The second is the ability to really slow down and focus on the way that the art and the text communicate together. The third is that the artistic part of it is intrinsically empathy driven. We identify with shapes that look like human faces. We can understand and look at contexts that can speak to us.

I don’t want comics to be used for teaching just because they are engaging, but they are also engaging. I work with hundreds of teachers with the OER Project, and they all love comics because students are immediately engaged with them.

How did you pick out these five comics about Africa’s history? What were your criteria?

There are a lot of bad history comics out there. They either contain bad history, or they’re bad comics containing good history. What we want to do is call out and specify, and help people understand, how a good nonfiction (or semi-nonfiction) graphic narrative can communicate things that can help you to develop your sense of the worlds that are being talked about. I picked these five because I think these are the best for communicating African experiences, African pasts and their meanings to readers today.

The comics I picked are, in my opinion, good histories. That doesn’t mean they don’t contain any fiction. Sometimes assumptions or connections or historical confabulations have to be made. They’re also good comics. Those two things don’t often come together.

Let’s start out in the South Africa of the 1970s and 80s, with a book called Crossroads: I Live Where I Like by historian Koni Benson and illustrated by the Trantraal brothers and Ashley Marais. Tell me about this book and why you’ve chosen it. Also, maybe start by explaining where Crossroads is?

Crossroads is in the Cape Flats, a very impoverished, sandy windblown area between the beauty of Cape Town and of the Cape Winelands. It’s where disposable people were put under apartheid—people who were needed for labor on the farms or as domestic workers in the city. They often moved there illegally from the overcrowded Bantustans (the so-called ‘black reserves’) in search of work. They weren’t supposed to be there, so they built informal settlements. They lived there and made an inconvenience of themselves to the apartheid government.

The story told in Crossroads is not about their suffering, per se. It’s the story of their resistance, told in their own words. It’s a history of an informal community that wasn’t allowed to exist and the women who successively resisted attempts to dismantle it, force everyone to move, and bring it into line. Koni worked closely with the local community to pull out their experiences while these women are still alive. The things they went through are horrible, but the ways in which they fought back—putting on plays, grabbing sticks and beating police informers and such—are amazing.

For the women in this book and the women who lived after them in Crossroads, it’s still a struggle to exist. This fight did not end with the end of apartheid. Both the apartheid government and the current government have tried to clear this area. It’s still a struggle to be in a place where, even in post-apartheid South Africa, they are not allowed to be. For Koni, this an ongoing, living story.

Most comics anywhere in the world are heavily influenced by either the French school or the Japanese manga school or American superhero comics. This book—not so much. You can’t look at this and say it’s a manga, because it isn’t. You can’t look at this and say this is a bande dessinée (BD). It isn’t. The artists, the Trantraal brothers, this is their style.

Koni Benson was a lecturer at the University of the Western Cape until quite recently. She wanted to do a ‘communography’: a biography of the community that she was working with as a scholar. She did it through oral histories—almost all the text is from oral histories or is explaining the oral histories—and then workshopping it through scholarly groups in the community. It’s beautifully group produced. It’s amazing.

“I work with hundreds of teachers…they all love comics because students are immediately engaged with them”

There are a lot of times where Koni and the Trantraal brothers—who are from the local Kaaps Afrikaans community—use visual metaphor. For example, Piet Koornhof, this horrible, apartheid-era Minister of Cooperation and Development, is shown as a snake, seducing the men into abandoning this movement for local rights, which was led by women. On that page, you don’t see the woman’s face, you only see her back, because she’s getting silenced. You’ve got to pause and take in that metaphor. It’s beautiful. You could turn to any page and the way these human beings are lovingly created—not hyper realistically, but empathetically—makes this book a great comic. And it’s also a really good community oral history.