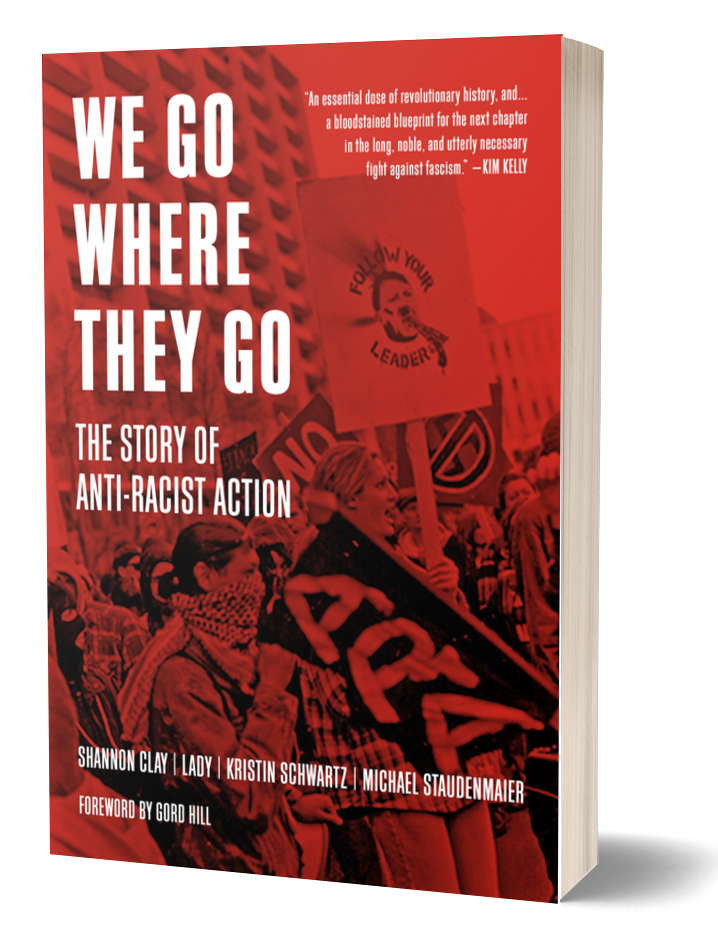

We Go Where They Go: The Story of Anti-Racist Action was published in January 2023. Based largely on interviews with past participants, the book documents and analyses the history of Anti-Racist Action (ARA), a youth-based network of groups and individuals, from the late 1980s until the early 2000s.

Among the interviewees was David McLaren, a long-time resident of the territory of the Saugeen Ojibway Nation, located on the Saugeen (Bruce) Peninsula in Ontario. He has been deeply involved in defending the Indigenous community against different manifestations of racism. He spoke at the 1996 Youth Against Hate conference in Toronto, organized by ARA. His stories are compelling. Because they did not fit within the narrative flow of the book we published, I asked him whether I could publish the interview transcript on the PM blog and he agreed. Thank you, David.

You can read more about the struggle of the Saugeen Ojibway Nation in this paper written by David and filed with the Ipperwash Inquiry in 2005. —Kristin

Territory of the Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation, view from Sydney Bay Road, 2019

Interview with David McLaren

October 9, 2020

Question: Tell us about your involvement with the anti-racist movement in the 1990s.

Up here, my involvement in anti-racist action was pretty deep. It was really based on what we could cobble together here on the reserve, Chippewas of Nawash, and the Chippewas of Saugeen; together they are known as the Saugeen Ojibway Nation. Starting in about 1992, there was backlash against the land claim that the Bands were beginning to research and file, and also backlash against the fishing. The Bands had decided together that they would reaffirm or affirm their fishing rights, and to go back into the water regardless of what the MNR [Ministry of Natural Resources] regulations were. That meant that they set nets outside the little postage stamp area that the MNR had mapped out for them on the water, and on both sides of the peninsula – on the Cape Croker side and also on the Saugeen side. And they just began to fish.

That invited charges and interference from the MNR. Around 1989, 1990, the MNR had actually charged a number of fishermen for fishing over their quota, which was really tiny. And in the court case, the Justice of the Peace [Justice Ross Forgrave] made them all stand up – about 10 of them were charged – and then lectured them for two hours on how to be a good conservationist.

I don’t remember if it was those charges or other charges, but the Bands decided to take this to court. The case proceeded on the basis of the 1982 Constitution which recognized First Nations Aboriginal and Treaty rights. In the spring of 1993, the decision came down. The Court found unequivocally that the First Nations did have these rights, and that the MNR management regime was therefore null and void and had discriminated against the First Nations.

Territory of the Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation, 2021

That meant the MNR had to think pretty quick. There had been a relatively active non-Native commercial fishery in this area, before that Court decision. The Court decision basically said, if you’re concerned about conservation, the non-Natives have to get out first, because the First Nations have a constitutionally protected right to fish. So that’s what the MNR did, by buying out the licenses of the non-Native commercial fisherman. There were about ten of them, I think. And these licenses are valuable. They were passed down from father to son, and if someone wanted to buy one they had to pay big bucks in order to get it. From what I understand, the government paid something like a million bucks each for the licenses, roughly. This is not small-time stuff. So, the non-Native fisherman vacated the fishery and the Native fisherman moved in as best they could.

But that didn’t mean that everyone was happy. There were some instant millionaires on the peninsula. But there were a lot of other mostly sports fishermen that were unhappy. They began to kick up a stink, that the Native fishermen were taking too many fish, that there was no control over them, there were too many boats out there. It was all bullshit. In fact, the non-Native sports fishermen held a derby, basically a contest to see who could land the biggest salmon or lake trout. And they would print the poundage in the paper every day. I added up all the poundage and looked at the Native fishery and it was a small fraction of what they were taking out. And I sent around a press release. And they were thoroughly embarrassed about the amount of fish they were taking out. They would take the fish that was caught, they used it, thank goodness. They cut it up and served it at 5 bucks a plate or whatever, but it was a huge amount and there was a lot of wastage.

At one point after the decision, the MNR decided that they could not ban Native fisherman from fishing, so they decided to ban the sale of the fish. It became illegal for people to buy it. Totally stupid. It was one of the things that the MNR tried to do to, in order to discourage the Native fishery. Eric Johnson said, “We should sell it anyway.”

So we sent around a notice to our friends in the churches, the Mennonites down in Kitchener and the Lutherans in Wiarton and Owen Sound and down south. We said: “You want to buy some fish? And by the way, if you buy it, you might get charged; it might be illegal.” And they said, “Sure.” So, we sold fish to anyone who wanted to buy it. We advertised, we sent around a press release to the media at such-and-such a place and such-and-such a time. It was no secret. The MNR knew very well what was going on. The CAW [Canadian Auto Workers] has a big educational centre at Port Elgin, not far away, which had made a conscious decision to be allies to First Nations in their struggles. And they said, “We’ll buy a whole whack of fish and feed it to our members when they come.” And the MNR came along and confiscated all the fish. When the dust all settled and the First Nations were firmly in charge with their fishery, the CAW asked for their fish back, of course the MNR didn’t have it anymore.

Guys would sell fish off the back of the truck on the reserve, off the reserve. The government didn’t appeal the court decision which meant the right to fish was constrained to the Saugeen Ojibway Nation. If the government had appealed and it had gone to the Ontario Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court, then the right to fish would have been much more broadly applicable, but they didn’t do that.

The non-Native fisherman decided to take things into their own hands. They began lifting Native nets. The Natives would go out in small open boats, 24 feet maybe, outboard motors. They would set their nets with markers on the nets, so that they would know where the nets were, identified with their Band number or something like that. Rudimentary, but they made it work. The nets were stable, safe. Whenever the anglers saw one of those buoys in the water, they would reach underneath and cut the net. This was really stupid if you’re professing to be a conservationist, because the net is set adrift and it keeps catching fish. It’s a ghost net, is what they call them. And they drift all over the place catching fish and you can’t pull it up because it’s under water. The OPP was running patrols in their motorboats, ostensibly looking for people doing that. Of course, they never found anyone, and I’m not sure how hard they looked.

But one of the fishermen set a little surprise for the guys who were cutting the nuts. He put razor blades along the line by the buoys, so that somebody who reached under the water to cut the net, they would cut themselves. He warned the OPP he was doing this to protect his nets. The police ended up charging him with “setting a man trap”. We had to find a lawyer for him down south – it would be stupid to try to find a lawyer here –and the lawyer got him off.

Then, there was a woman was selling her little bit of fish at the Farmers Market. I heard on the radio on Friday afternoon that there was going to be a meeting and a big march on the Farmers Market on the Saturday. I called her and she said, “This is how I make my living, I’ve got to go.” She and her daughter showed up. By that time, we had some allies, church people mostly in Owen Sound. I phoned them all up. I went down and some folks from the reserve went down. And lo and behold, the anglers marched down the road in town. Bill Murdoch, who was the MPP [Member of Provincial Parliament] at the time, was at the head of the little parade. They marched into the Farmers Market and made a big stink about the Native woman selling fish. Some yahoo had brought a salmon, half butchered. He took it out of the plastic bag and threw it on her stall and said, “Here’s one you didn’t catch!” We had a little press conference afterwards and I had the bag with the fish in it and said, “This is their idea of conservation.” The non-Native allies were pretty good. At one point it got pretty nasty around the woman’s stall, and the allies formed a cordon around the woman’s stall to keep the anglers at bay.

There was a lot of pushing and shoving. The MP showed up. He had been the mayor of Owen Sound before. Ovid Jackson was Black, a Liberal [Party] guy. I cornered him and asked him what he had to say about it. He basically shrugged. Interestingly, there was a relatively substantial population of Blacks in Grey Bruce – the descendants of escaped slaves who traveled from the US South on the Undergrounds Railway. Owen Sound was the northern terminus of the railway. Many left after the Civil War, but many stayed. The leaders of that community voiced their support for the Saugeen Ojibway Nation’s right to fish, even if Ovid stayed silent.

It was obvious we weren’t going to get any help from the Liberals. But this was the time of the NDP [New Democratic Party], provincially, and they were much more responsive. I remember phoning up the Attorney General’s office and said that they really should come up and listen to this Justice, Justice Forgrave, who had lectured the fishermen about being such bad conservationists. They came up and audited him. And they basically told him, “You either take a course that would allow you to recognize Aboriginal treaty rights and get with the program, or you leave.” And he left the bench. Which is great. When he left the bench, the OPP [Ontario Provincial Police] and the MNR conservation officers threw him a big party and gave him an award for being such a great conservationist. And that was the atmosphere that was up here. It was very much anti-Native fishing, and anti-Native land claims. And it was coming out in a physical way.

1995, in springtime, I remember reading an article in Maclean’s by Diane Francis. She was going on and on about Native people spoiling the environment. I remember writing a memo to Joint Council, saying this was promising to be a tough summer. And lo and behold, of course Ipperwash happened that summer, and Gustafsen Lake out in BC [British Columbia]. And the whole Native fishing thing on the Bruce blew up that summer. First Nation boats were vandalized. [First Nations] Band members were dissed on the streets of Wiarton and Owen Sound. One guy who had a tug – it was burned to the water line, completely destroyed. The net cutting kept going on. The police investigated the fire, but they didn’t have enough evidence to charge the guy who they suspected did it.

First Nations fishing boat deliberately scuttled, August 1995

First Nations fishing boat destroyed by arson, September 1995 (image from a CBC television documentary).

And that was the year, on Labour Day weekend that a group of Native youth who had apartments in Owen Sound were ambushed by a mob of about twenty people. They were sitting on their balcony and one [non-Native] guy threw a beer bottle and hit one of the First Nations’ men in the chest. And a couple more came up the fire escape in order to engage the Native people sitting there. The Native man backed them down the fire escape and when he got to the bottom, a whole bunch of white people who were partying nearby attacked them. So it was about four guys trying to battle at least twenty other guys. Two of the Natives were stabbed during the melee, another was beaten into the ground. And the cops were sitting there, in a parking lot about 50 yards away. And they watched it, according to witnesses. Somebody phoned for an ambulance because people were being stabbed, and only then the police moved in and started clearing people away. One of the guys who was involved was down on the ground, trying to get up, and he told me he remembers getting hit by the cops who were telling him to stay down. The ambulances came and took three people to the hospital. One guy’s face was slashed really bad.

I got a call the next day from one of the elders. She said, “David, I think you should know what happened in Owen Sound last night.” Now, when you get a call from an elder who says, “I think you should know this,” that means, “Go and do something about it.” So, I did. I tracked down the guys. I took pictures of the stab wounds, crudely sewed up. Took their statements, and we began to insist that the police do something about this. I heard there would be a hearing about what had happened. The Crown Attorney was very blasé about it and said there was alcohol on both sides, and it was a consensual fight.

And that began a campaign on my part, to have the justice system take it seriously. Nobody in Owen Sound wanted to be involved so we went wider. We had a press conference down in the city. Clayton Ruby part of it and so was the Canadian Environmental Law Association. Word was getting around. Our allies in Owen Sound did something very useful, very helpful. They held a demonstration outside the Court House, demanding that the justice system do something about this. The attorney they had hired to advise them shied right away from that. But at least it got somebody’s attention. The Regional Crown in London assigned Owen Haw, a very engaging and competent Crown from Guelph Ontario, to come up and poke around and to take over the case.

I said to the guys, “Put out the word. Somebody’s going to brag about what happened. See what you can find out by the grapevine.” And that did shake somebody out, and they did charge that person with aggravated assault. It should have been attempted murder.

Now, there were two guys who were doing the stabbing. One of the guys had gone into his apartment and changed his clothes and came back down. One of the Native women saw him do some damage and yelled at the police, “That’s one of the guys who did it!” The police picked him up, drove him out of the alley, and let him go. He never was charged.

But after being pushed and shoved and cajoled to investigate, especially by Owen, the police found a witness who was at the party, who saw the one guy come up to his apartment to get some knives and go back down. She gave her statement, but when it came time for her to testify, she wouldn’t talk; she had obviously been threatened. Even so, the judge did find that one guy guilty of aggravated assault and he got nine months, which was not very much, based on what he did.

But Owen was very, very good. He was tenacious with the police and in his prosecution of the case. One of the things he told me was that he had never seen such racism in the police – vocal, outright, not hidden racism – before in his life. He decided he would come up to the reserve and sort of explain why it was such a shitty sentence. He phoned me up in the afternoon and said, “David, the police have advised me not to come up because they said they couldn’t protect me on the reserve. Do I have any reason to be worried?” I said no. “They urged me to at least take a gun.” I was like “Oh my God, leave the gun at home.” He wasn’t afraid, he just wanted to make sure I knew about it. He did come up, alone, and basically apologized for the shitty sentence. He wasn’t happy about it and nobody on the reserve was happy about it. Of course, the community responded very well, and I think they were appreciative that somebody had done something. Otherwise, nothing would have been done, there would have been nobody charged.

The hate and opposition – it was really a coordinated affair on the part of the anglers. The Sydenham Sportsmen’s Association was basically leading the charge. They basically encouraged the OFAH [Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters] – although they didn’t need much encouragement – to mount a campaign against Native rights, an Ontario campaign. One of the things that they did was persuade their buddies in local newspapers to write articles about Native fishing and how it was ruining the resource, etc. All of these articles started popping up, all over the province, complaining about Native fishing and telling these stories of the “rape of the resource.” Those were their words. And it led to confrontations in the bush, not just here but also in other parts in Ontario. I remember talking to Doug Williams down at Curve Lake [First Nation]. He was telling me that he had guns pointed at him in the bush, when he went hunting. On Manitoulin Island, where there are a number of First Nations, the MNR ran a sting operation called ‘Operation Rainbow.’ Conservation Officers posed as American hunters whose vacation time was running out and the offered First Nations men money to go out and kill something for them. When they did, the COs would arrest them for hunting without a licence.

So, this was all over the province. Roughly about that time the OFAH had a big community meeting about aboriginal hunting in the Ottawa Valley. That was videotaped, and it didn’t go very well. There were lots of complaints from the audience about Native fishing and hunting. Only few people were there from the Golden Lake Algonquin Band.

We decided that we would join the OFAH. We made up some sort of name – “Nawash Fishing Club” or something like that. We paid our dues and began to go to all the meetings. It proved to be very strategic. It didn’t prevent the nonsense from happening in 1995, but it did confront the misinformation that was being given to hunters and anglers, in their own meetings. The sportsmen would argue with the guys about what they were doing to the fishery around the Bruce. And the guys would argue back, telling them they were just trying to make a living, not taking much anyway, and that fishing was part of Saugeen Ojibway culture. I understand that the OFAH began to lose a lot of members, because they were fed up with the campaign that was coming from head office. The president of OFAH was a guy named Davison Ankney. He was a biologist at University of Western Ontario. He happened to be a colleague, friend and ally of [notorious professor and eugenicist at University of Western Ontario] Philippe Rushton, the guy who was big on brain size. A bunch of bullshit. But in his day, he had some influence.

So that kind of racism was percolating at the time and fueled many of the confrontations.

Every year, the OFAH has a big presence at the annual Sportsman’s Show at the CNE [Canadian National Exhibition]. And that year [1995] they had a big poster display which they had put up on room dividers, of all the articles they had collected by the sports writers that they had coached, from all these local papers. There were a lot of them. I phoned up folks I knew in Toronto, Rodney Bobiwash and others and said this was going on and I’ll come down, let’s go and take a look. The morning of the day that these guys were going to take a look, the chief of Ontario folks called me up. Gord Peters said, “Why don’t you come to breakfast? We’re hosting the OFAH” At that time the Chiefs of Ontario strategy was to talk with OFAH and keep the lines of communication open. Of course, our strategy was to oppose them at every turn.

So Rick Morgan [the ED of the OFAH] turned to me and said, “David, we took a look at our posters and we took the most obvious ones down, so you can call off your guys now.” And I just smiled and said “They’re not my guys. They’re going to do whatever they’re going to do, I just told them what was going on.” As if I had some sort of control over how First Nations people were reacting to their silliness; of course, I had none at all.

Rodney Bobiwash and his crew had got into the show, and Rick Morgan had escorted them to the spot. They stood around and read all the posters, and then took them, one after another, off the wall. It was great. I hung around in the background while they were doing it, just listening to the comments of the OFAH people. They were pissed.

That’s the kind of stuff that we did. We basically turned the absurdity and stupidity of the racism against the organizations who were promoting it. That included selling fish, in spite of the MNR rules; it included going to the OFAH meetings as a ‘member’ club; it included taking down the posters. Of course, the press was there, because Rodney was no dummy – he made sure they were there – and they reported on all of it.

It was a long campaign and sort of climaxed in 1995 with the stabbings and the lifting of nets and burning of boats and all that. It began to taper off, but the MNR was still in the water and still harassing.

In 1995, [the NDP lost the provincial election and the Conservative Party was elected.] So the opposition was really coming from the government. One guy named Francis had posted his nets in the Meaford area, around the boundary line that the MNR had drawn in the water in recognition of the court decision. So, the area that was finally being recognized by the government went from Goderich all the way around the Bruce Peninsula to the Meaford area. Francis set his nets out around Meaford. He went to pick them up and he saw the MNR launch heading there. There was a big race, and the MNR beat him. And they just rolled up his nets. He could see his catch was lost and his nets were being ruined.

So that was the kind of official harassment – taking the nets out of the water, trying to declare that you couldn’t buy the fish, and harassing fishermen who got too close their lines in the water.

At one point the MNR decided to close the Native fishery. That was after the court decision, but they summarily closed the Native fishery. They announced, “You’ve got to be out of the water by midnight.” And this was in the fall. And you’ve got to be really careful in Georgian Bay and Lake Huron in the fall because that’s when the big storms come up, and they can come up in a flash, as the number of old wrecks of ships on the bottom of the Bay will attest.

One guy, who had married into the reserve and was fishing – he was Native, but had come from away – he went out in his little open boat to pull up his nets and a storm came up. He was thrown overboard and drowned. The boat was found the next day going in circles. He had lashed himself to one of the buoys but between the water and exposure he didn’t make it.

It turned out the order that the MNR had posted, closing down the fishery, was illegal! The Minister hadn’t signed it. I asked his wife if she wanted to do anything about it, but at that time, but she wanted to recover. But the MNR was at fault, and they should have been charged; there should have been some consequence.

There was no settlement of the whole issue until 2000, when the Conservative government finally threw up its hands and decided to sign something. That was the first agreement to clearly recognize First Nations rights to fish commercially in the area and set out, with agreement by the Band, overall quotas for the whole area and basically left the Band to regulate its own fishery.

The MNR continued to collaborate with the sportsmen in stocking salmon. That’s one of things that has wrecked the fishery. And not a lot of Native fishermen are out on the water because the whitefish population has crashed and the lake trout population isn’t much better. The original lake trout population was fished out in the 1950s and then the lamprey eel, decimated what was left. The MNR made an effort to repopulate the waters with lake trout, but they didn’t have the original strain. So they got a hybrid fish – a cross between speckled trout and lake trout, which they call splake – and they stocked the waters with that. Now the splake are finally beginning to reproduce naturally and they have been for a few years. But it was far too little, far too late. The MNR approved the stocking of Pacific salmon species by local sportsmen’s clubs. It was a huge mistake. They stocked a predator fish on top of another predator fish. What was left of food fishery was decimated by the salmon and also by global warming. The waters are getting warmer. The fresh water shrimp populations crashed, and that’s what the whitefish relied on. Whitefish has, for thousands of years, been the First Nations’ staple. It was one thing after another … all these things have acted together. I won’t say it has wrecked the fishery, but it ain’t what it used to be for First Nations fishers.

So that, in brief, is the story of the fishery. Things calmed down after the first fishing agreement and have stayed calm ever since then. At least relatively calm.

Question: What was your role in all of this at the time?

My official title was Communications Coordinator, sometimes for Nawash, sometimes for both Bands. I organized the incursion into OFAH, the fish sales, I sent the press releases. Extraordinarily stressful.

But I want to stress how hard it was on Band members. They were attacked in Owen Sound, disrespected in Wiarton, their boats were vandalized, their nets cut free, harassed by Mike Harris’ Conservative government. And yet the fishermen in particular would not back down. Anything I did I cleared with Chief and Council. Any formal letters were sent over Chief Ralph Akiwenzie’s signature.

I think you can say we won the ‘Fishing Wars’, as we called them. But that victory is rightfully to the credit of the First Nations.

Question: When you hear about what’s happening on the east coast [see, for example: https://ejatlas.org/conflict/mikmaq-fisheries-dispute), do you feel you are able to share some of the strategies you have?

Roger Obonsawin, a First Nations businessman, was asked to go down and talk to down to Burnt Church and the Mi’kmaq communities in the east coast. He asked me if I had any message for them. I said, “Keep fishing”. Folks there took it to heart. And it’s the same stuff. The Court recognized that First Nations have right to fish for a “moderate livelihood” – which should be average wage for the area – and non-Native fisherman are simply not recognizing that. And the DFO [Department of Fisheries and Oceans] are sitting to one side as the MNR did here, and actively working against the Native fishery.

Question: How did you know Rodney Bobiwash? [See https://nowtoronto.com/news/a-true-warrior/ for a profile published after his death in 2002.]

I can’t remember how. We were invited to a number of First Nations at that time, separately or together, to talk to them about racism and what was going on with the anglers and hunters, and how to combat that. I remember going to Curve Lake, and to Golden Lake with the Algonquins.

Side story –in Golden Lake we were talking about racism and what it looks like and how Nawash and Saugeen were dealing with it. I kept using the word “non-Native” of course. And there was a Black woman in the audience, and she finally piped up and said “You’ve got to find another word because I’m not a Native and that’s not me. I’m not part of that. We’re not part of that.” And rather than getting upset, people in the room began to throw up alternatives to the word “non-Native”. “Pigmentally challenged”. “People of pallor”. It was hysterical. Didn’t hear from her after that. Besides, we’re all newcomers and people of all colours and ethnicity have a responsibility toward reconciliation too.

Rodney and I developed a relationship through those meetings. He actually came up to Owen Sound when the anglers and hunters had the same kind of public meeting as the OFAH had in the Ottawa Valley. This was a couple of years after that Ottawa Valley meeting. They did the same thing in Owen Sound, saying, “We’re not against anybody’s rights, but we’re concerned about conservation, and besides, we contribute a lot of the economy when we hold our fishing derbies.” Yadda yadda yadda.

Representatives from the MNR were there and spoke too. At one point they said how much they had spent on the whole fishing issue. I stood up and said, “Tell the whole story. How much did you pay the non-Native fisherman?” Of course, he didn’t answer because it was in the order of $10 million just to buy out their commercial licences. Linda Thompson, one of our allies, later told Rodney and me that she had overhead two guys, one saying, “Somebody’s got to get that McLaren,” and the other saying “Well, I have a rope in my truck”. It was so stupid and cliched. Rodney and I just looked at each other and burst out laughing. So Alabama. I never had any threats directed at me though. I am pretty sure my phone was tapped for a while. Got a couple of threatening calls on the office phone. But I was never followed or anything like that.

Question: Do you remember ONFIRE?

Flash in the pan. They said a lot of hateful things at the time the OPP killed Dudley George, but they never had a presence up here on the Bruce Peninsula.

Question: You were at the Youth Against Hate conference in June of 1996. What would you say about it?

I thought it was a valiant attempt by ARA to begin a conservation, but I don’t think that it went very far. I remember the representative from the Simon Wiesenthal Centre saying that their greatest ally was now the police, because they could coordinate with the police, and the police would take racism against Jews seriously. When somebody asked me the question about the police, and I said the police were part of the problem where I came from. And indeed, they were. And that’s really all I remember about the conference.

I do remember another conference I went to, of the Canadian Race Relations Foundation. This was a large conference. Lincoln Alexander was the chairman at that point. I got up to the podium and had comments all prepared. I looked out over the audience. It was like a who’s who of Ontario political power. Roy McMurtry, former Attorney General. Representatives of the Archbishop’s office. A pretty stellar crowd. I remember saying something like, “If we had this much support when things broke out up north, we’d have no problems at all.” But I remember looking Roy McMurtry right in the eye when I told the story about Justice Forgrave, and I thought he might come up to me afterwards, but he didn’t. A representative of the Archbishop did come up to me after. He was immaculately dressed in a beautiful black suit, and a gold cross hanging around his neck. He asked if I could put him in touch with people at Nawash because he understood there’d been a priest up there who had abused people. There was – Father Epoch who was outed and sent off to another First Nation where he undoubtedly recreated his crimes. I looked it at him, and I almost told him to fuck off. This was years after his crimes, after suicides because of that abuse. And now the Archbishop has the temerity to come and ask me if I could put him in touch? I said, “They have phones, you know. Call them yourself,” and I walked away. It really showed me just how indifferent the powers-that-be were to the kinds of racism happening in their back yard.

Another story. In 1996, W5 told us that they were going to come up and talk to us about the Nawash and Saugeen fishery. It was after a bad car accident so I was hobbling around on crutches, but I really wanted to hear what this guy had to say. He was interviewing the chief. When the camera was off, he was all milk and honey: “Nice place you have here. How many people do you serve?” and so on. On camera, the questions were kind of sharp, like “The sportsmen are only trying to bring back the fishery.” I could tell that this was going to be a hatchet job. I challenged him: “Why don’t you ask about the OFAH opposition or the MNR’s harassment?” Next thing I know I’m in an OFAH meeting and [president of the OFAH] Davison Ankney can’t help himself. He’s at the front of the room bragging that he had got W5 to take a hard look at Native fishing and hunting. So, I knew where it was coming from.

So that’s the kind of stuff that went on, and we’re not even talking about land claims. There was a whole bunch of shit happening about land claims at the time.

Question: Tell me about your relationship with ARA.

It was good and comforting to know that there was a group of young people who were confronting racism on the streets. The racists did make an incursion into the local high school. There was a bit of recruiting going on, but it never got far. But it was good to know that you were there in case it did. That was basically it.

For my money, I’d say that ARA was probably the most effective organization confronting racism at the time. The Canadian Race Relations Foundation was okay at a higher level with their conferences and papers. The churches – except for one or two – were useless. The Catholic Church was just a total write-off, couldn’t get them engaged at all. The United Church – only one guy was engaged. He was the minister up in Tobermory. The congregation ran him out; they said, “You’re siding with the Natives, we don’t agree with that, get lost.” And the United Church didn’t back him. They should have. They should have said, “Well, if you don’t like this guy, we’re not going to send you another one.” The government of course was on the other side of the table. The academics, with one or two exceptions, were hopeless. I could not get them engaged. And I tried. The Mennonites and the CAW were good allies. They stood up.

Racism is clearly a white problem. It’s not for First Nations people, who have enough on their plate at it is, or Black folks who are getting carded every time they walk out the door, to deal with it. It’s our problem, as white people, and we should be dealing with it. Sure, I was dealing with it up here, but I felt very strongly that there were other people who should be dealing with it as well. When I found an ally, in Owen Sound or Wiarton, or with the Mennonites and CAW, they were very good and they did make a difference. But in terms of a church, like an institution, standing up and ex cathedral, from the pulpit, condemning the racism that was going on, no. They just didn’t do it.

Question: Do you think there’s been any movement or change since that time?

I think so. You know, the demographics have changed a little bit in this area. More people have been coming from outside. I don’t think that the anglers and hunters could get away with what they did back in the ‘90s, now. There would be backlash, from the white population. And there are still allies around and I know if it ever happened again, that I know we could call on them and it would be effective. But has it gone completely? No. I don’t think this stuff ever goes away. It goes underground, becomes unpopular for a while but when it becomes okay again it will erupt. And what you see happening right now, is that you’ve got Donald Trump south of the border. And he’s making it okay for racists to be racist. And there’s a reflection up here. You see it in the opposition to masks, social distancing, vaccines. You see it in the reaction to Black Lives Matter protests in Canada. It’s there, it’s still around. It’s like a groundfire. It goes underground and burns for a while and will flare up again. Hopefully it won’t here. The demographics have changed too much in this area. But you know that it’s there.

Question: [Kristin describes the work of the activist group SURJ – Showing Up for Racial Justice. David asks whether SURJ reaches out to young people.]

I think that anybody that does anti-racism work of any sort has to find white allies. It has to be white people condemning white racism and white supremacy. Blacks are obviously making their voices heard, and that has to happen, but the grunt work has to be done by white folks. Finding white allies, and strong white allies, is crucial for any campaign. But I wouldn’t rely on institutions. Find those people within institutions who are willing to stand up, and who might be able to drag their institutions into the fight. But it really is individuals that need to make a difference.

Confront. Confront. Confront. You can’t just stand back and write letters to the editor, although they are helpful and white allies should be doing that, the more the merrier. But you’ve got to get out there on the street and confronting whatever raises its head. And I think that’s the value of ARA. That you weren’t afraid to get out on the street and go after them, even if they were hiding out in a bar somewhere. That’s just what you have to do.

It can get to the point where it is now in Michigan, where they’ve uncovered a plot to take the Governor [Gretchen Whitmer] captive and overthrow the government. The FBI busted a ring of 13 guys who have been practicing demolition and using live ammo. They were planning to kidnap the Governor. And this is a serious thing, not a bunch of yahoos who are out to lunch and playing at being revolutionaries. This is an organized white supremacist militia with guns who were planning to do this. Serious business. And that’s the length to which it can go. The Governor was not shy about laying the blame for this at the feet of Donald Trump. And I think it’s true.

One of the things that’s happened, is racists have been given permission. If someone says, “You guys [racists] are okay,”or “There’s good people on both sides,” that’s giving license for them to go out and do shit. You have to be careful about what you say. When they feel they have permission, usually from a head of government, that’s when the damage begins. Whether it’s Stephen Harper or Mike Harris or Donald Trump. That’s what twigged me into what was going to happen in 1995. It was not only the election of Mike Harris, but all the stuff I was reading in the papers. All the complaints about Native hunting and fishing rights. Their voices were being validated. Their concern for conservation was really a cover for hatred. You have to watch out for covers. What is it that is being used to cover the hatred that is beneath it? Now it’s masks, and social distancing and vaccines. And it’s, “Black people burning down their own neighbourhoods, and rioting and doing property damage – how can they possibly be human when they are doing this stuff?” And besides, our law enforcement can, in a very blasé matter, kneel on their backs for eight minutes. So, that makes it okay to march for white supremacy with tiki torches in Charlottesville.

You can say all kinds of things, but it’s a whitewash. People have to be aware of when they’re being whitewashed. So, allies – watch out for language, and when permissions are being granted. Confront it. As soon as it rears its head, you’ve got to go confront it. The other lesson is that you’ve got to involve the youth. You have to involve them in the fight. Because they need to be instructed how to see this stuff, and what to do about it. Some of them need to be deprogrammed. And, don’t trust the police. They are not your friend.