Contents

Introduction

Across the globe grassroots food activists work to end hunger, strengthen communities, challenge inequality, and create sustainable social and environmental alternatives. Nourishing Resistance: Stories of Food, Protest, and Mutual Aid is a collection of essays, articles, poems, and stories from 23 cooks, farmers, writers, organizers, academics, and dreamers who demonstrate that food is a central, intrinsic part of global struggles for autonomy and collective liberation.

In this book extract Virginia Tognola chronicles how practical solidarity in the form of street kitchens and the “popular pot” has not only enabled migrants and others in Argentina to survive but also acted as a way to raise issues and campaign against sub-standard living conditions.

Book Extract

On the sidewalk of one of the typical conventillos, or family hotels (as they call illegal pensions that house families in precarious situations), in Constitucion, a poor neighborhood in Buenos Aires, people bring what they have to a giant pot heated over a makeshift fire in the street. Suleika brings potatoes and salsa, Mariela vegetables, Juan Pablo a chicken, and Daniela Trujillo several pounds of legumes contributed by the Frente de Migrantes y Refugiadxs of the Movimiento Popular Nuestramerica, where she militates. They cook stew, a meal characterized by being made, literally, of what you have at home: vegetables, noodles, rice, lentils, meat, broth, sauce—whatever there is with a little water to bind well.

A sign next to the fire reads, “Olla Migrante.” In an interview I conduct with Daniela to find out what their work is about, she explains, “This stew is a tool to begin to build a closer bond between the migrant residents of Constitucion. It was originally made in different sidewalk hotels once a month and emerged from the dining room of Galpon de Octubre, a communal political space that is part of the Movimiento Popular Nuestramerica, where neighbors and activists on a day-to-day basis got to know each other while chatting in line while they waited to be served.

There, it was clear that there was not only a need for a plate of food for migrants, but also to attend to poor housing conditions and the fact that they could not get a job because they did not have identification documents, that they were uninformed about the citizen regularization of migrants, among other problems.”

These neighboring hotel dwellers cook in the street to visibilize the main grievance of the migrant sector, aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic: the inhumane conditions in which owners of illegal hotels house people who come to Argentina without money or contacts to help them. At the hotels, basic hygiene and safety conditions are not met, nor are there contracts stipulated by institutional regulations, so tenants are left to the good of the owners, who do not hesitate to evict entire families when they fall behind with the rents. These conventillos mostly house poor people who come to Argentina looking for better futures and who have no choice but to accept the cheapest rent they can find.

“Although the main objectives we pursue as migrant and refugee activists are migration regulation, decent housing, and decent work,” Daniela tells me, “the pandemic forced us to attend to basic human rights that were being violated in the midst of a health crisis where, in a hotel, you share a room with eight people and isolation is not met, in addition to the risk of staying on the street due to the evictions that occurred even though Decree 320/2020 prohibited them. Cooking the pot on the street is a way of showing the situation in migrant hotels: living in precarious conditions, overcrowded, with appalling sanitary conditions.”

For people in a situation of social vulnerability, getting together and generating networks of collective containment is vital, because in this way they gather strength, socialize information, and arm themselves with courage to pressure the government so that their human rights resonate.

Daniela adds, “Understanding that the way out of problems is collective and that no one is saved alone in the middle of a health, economic, and cultural apocalypse, we need to create beautiful and healthy ties with the people around us and to be able to count on them for life.”

Cumbia blasts from a loudspeaker pointing down a street cut off to traffic as dishes begin to pass from hand to hand. Some eat standing up, so they don’t waste a minute of dancing, others sit in chairs or on the floor, taking the opportunity to chat between bites, and others constantly interrupt, asking that we respect social distance to take care of each other. When they finish lunch, those who were serving food make themselves available to diners for any help they need with immigration procedures, evictions, or anything else. They also make themselves available to talk more about the organization and—why not?—discuss politics.

It is after dinner that is the most important moment in the history of social struggles. Strikes, revolutions, marches—everything takes place when digestion begins.

The cooks finish thanking those who came to eat, and the rest of those present applaud loudly. Everything that is said is said from the heart and from the need for struggle and popular organization to confront the injustices experienced.

Facundo Cifelli Rega, Nicolas, and Amy—other members of the communal political establishment Galpon 14 de Octubre—come to help clean the popular pot. This galpon worked for many years as a space for assistance, advice, and self-management to attend to the problems of the neighborhood, but since the mandatory social isolation began in March 2020, the tasks changed and they began to deliver at least six hundred plates of food weekly.

Facundo, who is one of the managers and activists of this local of the Movimiento Popular Nuestramerica, also gives us his testimony: “From our organization we had the possibility of starting up a dining room for the pandemic and the food shortage that was going through a large part of society, especially the most vulnerable sectors, even before isolation due to the economic destruction left by four years of the neoliberal government of Mauricio Macri, which greatly destroyed job opportunities and impoverished the people.”

The work of feeding so many people is only sustained with the will and absolute dedication of those who come together to plan the menu, chop ingredients, and think up and spread donation campaigns to sustain the work. These people take as a vital responsibility the struggle and daily effort for a world where, first, no one lacks food and, second, no one has to ask for food. This is because hunger is not accidental and has a social structure that enables it to exist, as Facundo mentions: “We realized that, although there was a need and a food crisis, behind that there was an even bigger crisis that gives rise to that, which is the lack of work. If you have not resolved that, it is very difficult for you to have access to healthy food. Even we ourselves as militants and volunteers from the dining room had that job instability.”

Those same people who lend a helping hand to cook are also impacted by the job crisis. Several lost their jobs during the quarantine and began to think, while chopping vegetables, about a joint way out of this problem. In Argentina, it is not news that the formal market does not contain the vast majority of people who need to enter the labor market. The first option that occurred to them was to set up work cooperatives depending on what most of them knew how to do: some could cook, some could sew and mend clothes, and others even knew how to make craft beer, so they set up a textile fair, a gastronomic venture, and a beer making one to start producing self-managed work. In this labor scheme, logics and forms of production are put into play outside of capitalist exploitation. As Facundo explains,

In cooperative work without a boss, workers can begin to establish other types of relationships among themselves which are more democratic and horizontal, both in grassroots work as well as in leadership and each labor instance. From all this, one can think about work in terms of other human objectives outside of the individual accumulation of capital and unscrupulous profitability.

Cooperativism is an alternative form of work to the formal economy, a labor system that excludes millions of people because they are racialized, feminized, migrant, et cetera. For all of them, a regular job is a kind of promise of well-being that will never come, because what actually happens is that the vast majority of poor people are born in and die in poverty, and in between they work informally, without recognition of basic rights. Accepting that the formal market excludes and that the majority of the population never enter into it is to talk about the elephant in the room and begin to shape an identity as a worker who is part of the popular economy, with its various rules and cultural representations. There, the popular pot is the star.

“As a Colombian migrant internalizing myself in Argentine history and all the struggles that took place here,” says Daniela, “the fight was always won by cooking in the streets. To be heard only by bureaucratic means is insufficient, because sometimes the problems are urgent and there is no answer, so people have no choice but to go out and express their anger, and that is a way of saying, ‘I’m here and you don’t fuck with me.’” In this country, the piqueteros movements—which were first made up of huge numbers of workers unemployed by the crisis that exploded in 2001 and then formalized year after year into organizations that push politically with para-institutional methods to reaffirm or achieve rights—have strengthened their symbols of protest during the last twenty years: the traffic cut, the chants, the burning of tires, the cacerolazos, the popular pots. Each of these symbols has a political and cultural functionality and, adds Facundo, “Here the popular pot is a very important flag of struggle. In the crisis we went through in the 1990s and in 2000, people found there a place of resistance, solidarity, and organization. Beyond the fact that, as a dining room, we are giving social assistance—that of feeding—we are also symbolically organizing and doing something beautiful, because cooking is an act of love. In the pot we are covering a need, organizing ourselves, and providing a little love with what we do.”

The goals and dreams anti-capitalist experiences pursued are sometimes utopian, but they do not neglect today’s needs for that reason. After all, who could plan revolutionary futures on an empty stomach?

In a system of death such as capitalism, social inequalities intensify year after year and relegate many people to a life spent in misery. The organization and collective struggle are a way out of that social determinism .In the cooking of stew, the knowledge of Indigenous people making claims for their stolen lands is mixed with that of those who are on the streets and cannot access their human right to a home of their own, and also with the demands of women who do not want to cook and wash dishes because it takes up their time for politics, and with the migrants who demand that we should not forget that xenophobia is supported by laws.

All the historical struggles against oppressions are part of the recipe. The popular pot is a thousand things and has a thousand meanings for those who fight for better living conditions, and it takes on a crucial importance when it demonstrates that hunger is solved with what we have at hand: popular organization and empowerment.

Book Overview

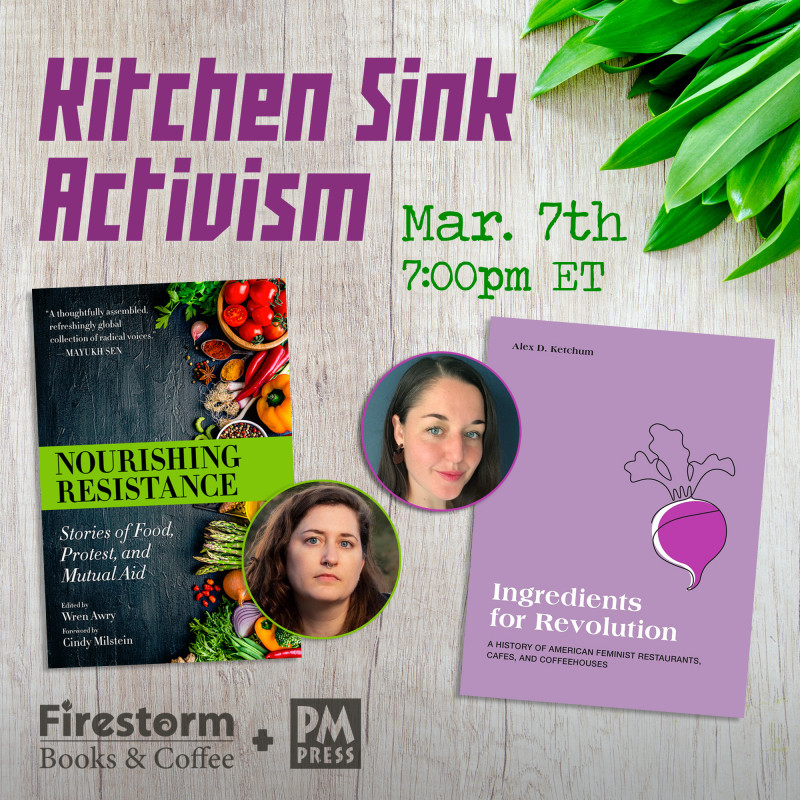

From the cooks who have fed rebels and revolutionaries to the collective kitchens set up after ecological disasters, food has long played a crucial role in resistance, protest, and mutual aid. Edited by Wren Awry, Nourishing Resistance centers these everyday acts of culinary solidarity. Twenty-three contributors—cooks, farmers, writers, organizers, academics, and dreamers—write on queer potlucks, rebel ancestors, disability justice, Indigenous food sovereignty, and the fight against toxic diet culture, among many other topics. They recount bowls of biryani at a Delhi protest, fricasé de conejo on a Puerto Rican farm, and pay-as-you-want dishes in a collectively run Hong Kong restaurant. They chronicle the food distribution programs that emerged in Buenos Aires and New York City in the wake of COVID-19. They look to the past, revealing how women rice workers composed the song “Bella Ciao,” and the future, speculating on postcapitalist worlds that include both high-tech collective farms and herbs gathered beside highways.