By Ann Holder

Science & Society

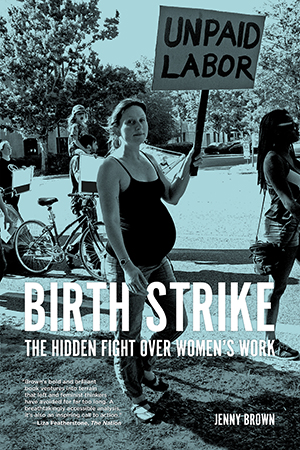

Jenny Brown’s provocative Birth Strike examines the gulf in the United States between popular support for women’s rights to reproductive control and the increasing hostility of state institutions — including as of Fall 2020 a 6–3 anti-abortion majority on the Supreme Court. Brown asks why this is happening. If you think you already know the answer, Birth Strike may convince you otherwise.

Published in 2019, Brown’s book provides a sweeping materialist reconsideration of reproductive politics, asserting that the extreme wealth gap and demographic trends in the USA play an outsize role in fueling (and funding) anti-abortion politics. Wielding a convincing collection of data, she insists that

the monied elite know their advantageous position depends on population increase. Denial of women’s reproductive control is a central element in a coordinated and coercive strategy to reverse rapidly declining birth rates.

From the vantage point of the 2020s, Brown’s prescience is apparent. New data released in May 2021 showed a birth rate decline of 4%, double that of the previous year (with an astonishing 8% drop for women ages 15–19). Handwringing commentators fretted that the trend would be difficult to reverse. Interviews with women suggested financial stability and career were competing with motherhood, and work was winning. By July of that year, state legislatures had passed 90 new laws restricting abortion.

For Brown, it was not so much that work was winning, but that women and families were besieged. As women chose — or were increasingly economically compelled into — remunerative labor, the “double day” of work and parenting became unsustainable. Having children meant assuming the costs and pressures of childrearing, being shamed or stigmatized as failed mothers and losing their independence to the unpaid labor of family life. The result, according to Brown, was an unorganized, inchoate “birth strike,” reflecting the simultaneity of independent decisions, by large numbers of women, to delay childbearing or not to have children at all.

This “birth strike” is not distinctive to the United States. Since its peak in 1964, the global fertility rate has dropped by more than half. For the political classes this constitutes a crisis — the BBC announced a “ ‘jaw-dropping’ global crash in children being born” — though Brown argues the only “crisis” is the threat to the monied classes.

A brief global overview provides a comparative approach that frames the choices made by US policy-makers. Some nations, France and Sweden for example, embraced openly pro-natalist policies that encouraged parenting as a social good. These included free childcare, paid parental leave, substantial

holidays, supplemental income, and universal health care, coupled with public access to reproductive control. Adequate tax rates broadened the social responsibility for childrearing. These policies worked; both nations hovered at or near the top of EU fertility rates over the last decade.

By contrast, the US strategy has been both miserly and punitive. Brown details an unspoken pro-natalism that shifts the burden from state and society to individuals. Women, denied access to reproductive control, are refused maternal and infant health care. Already marginalized women who bear children are stigmatized as irresponsible, tacitly justifying denial of public support to all families. The decision to have children is cast as an individual consumer choice, and struggling families are sentenced to self-blame. Unsurprisingly this approach disproportionally impacts poor women, women

of color, young women and mothers without partners. Those who benefit most from women’s labor bear the least responsibility.

As Brown shows, the emotional and financial costs in the United States are staggering. No wonder women increasingly resist this unacknowledged exploitation, even if they desire children. While their responses may not be intentionally collective, for Brown these decisions reflect a shared ethos

with potential power.

Brown highlights the connections between demographic politics and the sphere of “social reproduction” — the essential, though unacknowledged, work of childrearing, family nurture, and social care that was the presumed work of women. Social reproduction was inherently unpaid, unrecognized and burdensome, especially for women who had to work outside the home— often in humiliating conditions and for low wages — simply to subsist.

Brown’s strike metaphor highlights the role of uncompensated work in population replacement, and shows individual women spurning this form of labor exploitation by limiting childbearing. Brown brings this point home with the publication of women’s testimonies. In Chapter 3 she pivots away from the big picture analysis, and gives readers an intimate glimpse of women contemplating childbearing. Each

woman expresses her relationship to choices that feel predetermined. Fears of stigmatization, financial hardship, exhaustion, loss of independence and “mom-shaming” surface, albeit differently. The women are articulate about their predicaments, but less conscious about the larger political context that

produces them.

If there is a weak point in Birth Strike, it is Brown’s explicit rejection of cultural analysis. In her refreshing determination to restore the import of structural and material realities, Brown misses an opportunity to show that the production of gender is not limited to the actions of the “power structure.” It is also ensconced in the power of everyday assumptions and exchanges. Brown’s analysis would only have been strengthened by showing the synergies of culture and materiality; her decision to foreclose that possibility is puzzling. Nevertheless, her insistence on materiality reminds readers of how women’s bodies have historically been used and abused to achieve population interests as framed by the economically powerful.

Brown finds the current reproductive rights movement overly focused on a cultural debate it cannot win, because it does not understand its terms. For instance, activists frequently point to an apparent inconsistency: lavish concern by abortion’s opponents for “unborn” life, juxtaposed with their fierce opposition to public support for “post-birth” children and families.

Brown’s demographic analysis suggests this is misplaced. If the goal of the “power structure” is to produce more children, at the least cost to themselves, the inconsistency resolves into a rational, if horrifying, plan for cost-effective population stimulus. Women’s rights disappear from the debate.

Birth Strike repeatedly shows how the discourse that matters may remain hidden behind political truisms. Brown’s analysis suggests a rationale lurking behind arbitrary cruelties such as family separation. Employers need “instant adults,” workers lacking the protections of citizenship and unencumbered by families. For xenophobes, even this exception is too risky, but the separation

of children from families makes permanent residence much less likely. As with legal residents, immigrant communities are faced with an assault on families. Cross-movement collaborations, alongside awareness of demographic politics, are thus critical to contesting the instrumentalization of all bodies.

This book should be required reading for social justice activists. Brown’s hope is that reproductive resistance might yield a common consciousness of exploitation, and target “those who are benefitting from our reproductive work but not contributing to it.” Such a transformation might also have the power to “leverage” women’s control over childbearing and create “better conditions for the work of reproduction.”

But whether or not an intentional birth strike materializes, Brown reminds us that women’s reproductive control is critical, that childrearing is valuable and necessary labor for the common good, and its collective support is imperative for creating a world that benefits the many rather than the few.

This makes Birth Strike a major achievement.