By Steve Early

New Politics

October 7th, 2022

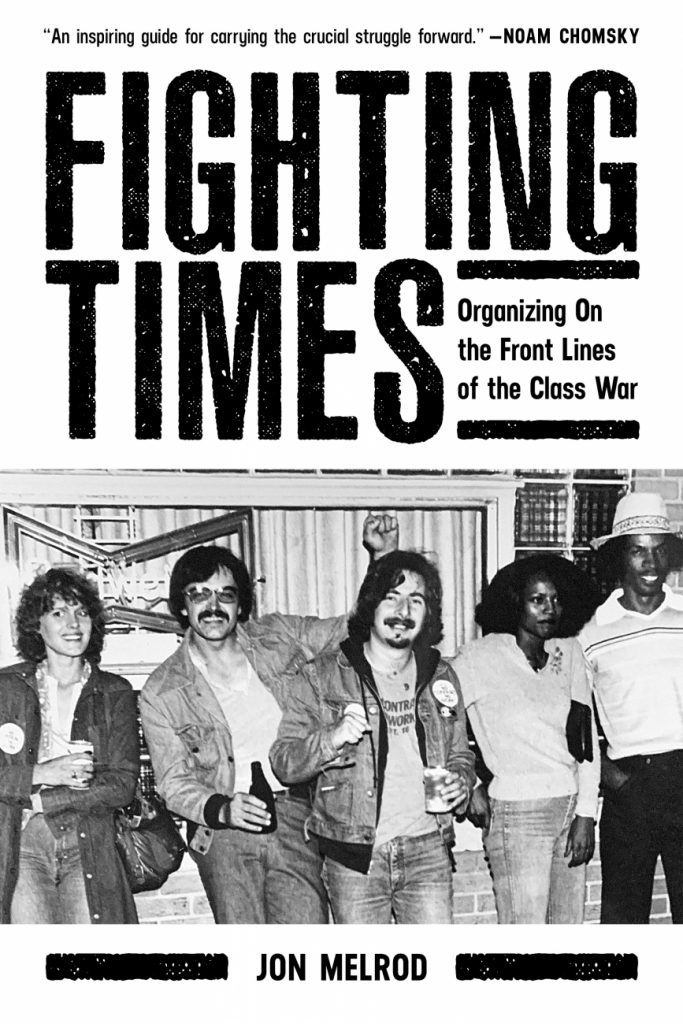

A review of Fighting Times: Organizing on the Front Lines of the Class War (PM Press, 2022) by Jon Melrod and Troublemaker: Saying No to Power by Frank Emspak (available at Amazon books).

The University of Wisconsin at Madison was a hotbed of student radicalism in the 1960s. Unlike some other centers of campus opposition to the Vietnam War, left-wing activists there were among the first of their generation to organize around issues related to their own mistreatment as workers. In 1963, undergraduates employed in campus jobs formed a Wisconsin Student Employees Union to force the administration to raise their wages to the federal minimum (a 50 cent per hour increase). Seven years later, the UW Teaching Assistants Association organized the first TA strike in U.S. history, a 24-day walk-out that won union recognition. UW graduates shaped by that experience went on to play key roles in the labor movement, locally, state-wide, and in others states. Two members of this UW alumni network, Frank Emspak and Jon Melrod, have just published autobiographical accounts of their parallel transition from being Marxist students to blue-collar workers in unionized workplaces in the 1970s and 80s.

At the time, they and their closest comrades were not exactly the best of friends or workplace allies. As Emspak reports in his memoir, Troublemaker, he came from a distinguished old left labor family. His father Julius, was a key organizer and longtime national officer of the United Electric Workers (UE), a union built with the help of Communist Party (CP) members or sympathizers in the 1930s. Melrod made his personal post-graduate turn toward industry as part of a group affiliated with the Revolutionary Union (RU), a Bay Area formation that later morphed into the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP). RCP cadre considered the CP to be a case study in Marxist-Leninist “revisionism” and were not fond of its labor work either. Both authors are trying to reach an audience of 21st century socialists who are, in some cases, young enough to be their grand-children. To most (but not all) in that new generational cohort, differences between the CP, the RCP, and other “alphabet soup” groups from the sectarian left of five decades ago will be of minimal interest. What will hopefully draw readers to Troublemaker and Fighting Times are their granular lessons about building left-led union reform caucuses, which can actually oust old guard officials and replace them with rank-and-file militants more committed to membership mobilization and strike activity.

A Catalytic Role

Today, that kind of internal struggle is more likely to occur in education, healthcare, or service sector labor organizations, rather than older industrial unions. Younger labor radicals who’ve become 1970s-style “colonizers” are more apt to choose workplaces or firms—like Starbucks or Amazon–without established unions so they can play a catalytic role in new organizing or first contract struggles. However, Melrod’s former union, the United Auto Workers (UAW) is currently in the midst of a first-ever direct election of its top officers, which has created a new political opening for UAW dissidents. And, with a recent national leadership change for the better in the Teamsters, Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU)—formed 46 years ago with much socialist help–is now well positioned to shape contract campaigning in the nation’s largest private sector bargaining unit, which covers 230,000 workers at United Parcel Service.

Melrod and Emspak both describe workplace organizing in an era when national bargaining on that scale was still the norm, rather than the exception, and unionized manufacturing had yet to be decimated by de-industrialization. Even when good-paying factory jobs were far more plentiful, however, management and its labor union partners had a shared interest in barring the door to former campus agitators like the authors. In Fighting Times, Melrod describes how he got hired at American Motors Corporation (AMC), then the nation’s fourth largest auto manufacturer, with a little help from job application falsification (which, when discovered, led to his first contested firing).

Emspak faced unique challenges landing a job at General Electric in Lynn, Massachusetts, then the largest industrial complex in New England. There was no concealing either his advanced degree (a PhD in labor history from UW) or a family tree, well known to the company, which helped oust the left-led UE from Lynn and other GE factory locations in the early 1950s. Not only was his father Julius a former GE worker, but so were five other members of two previous generations of his union building family. Even after the post-war legal and political assault on the UE, its more compliant replacement, the International Union of Electrical Workers (IUE) still had to contend with “a large group of workers who had a strong sense of what a real union could be” and welcomed the chance to unite with “a new generation of class-conscious troublemakers.” Emspak became one of the latter at GE only due to the fortuitous intervention of two under-cover UE sympathizers. One helper was a foreman who hired him without the knowledge of higher ups in the company, and a second, was a shop steward, who counseled Emspak not to sign an IUE membership card, alerting the union hall of his hiring, until he had completed his probationary period and could only be dismissed for just cause.

Once on the job, both authors faced the challenge of making friends and fending off enemies, of whom they had many in management and the union officialdom. Both had trusted political comrades they could count on, when faced with heavy red-baiting, often accompanied by physical threats. (On one occasion, Emspak was assaulted by hostile officials from other IUE locals when he attended a national union meeting and spoke out against GE proposals for a two-tier wage system,) Neither Melrod or Emspak would have been effective workplace organizers without joining social networks based on after work partying, sharing meals on the job, or, in the latter’s case, becoming a fellow gardener on a company-provided plot for machinists at a UE shop where he worked before joining the IUE at GE.

Shop Floor Leadership

Both memoirists stress the importance of publishing rank-and-file newsletters or revitalizing local union committees as a vehicle for addressing shop floor issues often ignored or downplayed by higher ranking union officials. Melrod’s opposition caucus in UAW Local 72 in Kenosha, Wisconsin published Fighting Times, which highlighted stories about job discrimination and harassment at AMC. As the paper “became known as a voice against racism … at election time, we could rely on many workers of color and women who viewed us as their stalwart defenders.” In IUE Local 201, the “left militant coalition” that Emspak helped to build was heavily represented “on the health and safety committee, the women’s committee and the new technology committee—groups that believed in and tried to implement membership-driven actions for health and safety and against sex bias and the challenges of new technology.” At AMC, as Melrod reports, wildcat strikes were often the weapon of choice against speed up and other abuses of management authority. At GE, the IUE contract included a rare open-ended grievance procedure, which made it possible for workers to strike, legally and during the life of the contract, over unresolved grievances, if the action was approved by the Local 201 executive board. Both Fighting Times and Troublemaker are filled with colorful and instructive accounts of direct action on the job, a tradition currently undergoing a revival in some non-union workplaces.

Helping to lead shop-floor struggles made both authors viable candidates for local union leadership positions. In Local 72, Melrod first became a steward, then chief steward, UAW convention delegate, and member of the local executive board and bargaining committee. Emspak was elected to the IUE’s national GE conference board and four times as a Local 201 executive board member, representing 1,000 workers at a satellite plant in a GE local with a total membership of 8,000. He mounted a strong local-wide campaign for assistant business manager, losing by a mere 38 votes out of 4,834 cast. In a second bid for the job, he and other militants were defeated after a plant-wide strike over accumulated grievances “lasted a month and achieved almost nothing.” By stonewalling the union and “making its progressive leadership look incompetent,” GE was able to install a “less confrontational group” at the 201 hall. During their union careers, the guidance that both authors received from their outside political organizations was not always helpful or supportive. When Melrod became less of a “polemicist”–and spent more time listening to and learning from his co-workers–fellow revolutionaries safely removed from the factory floor accused him of being a “Menshevik.” Emspak found himself at odds with the Communist Party, on several occasions, when he became part of a “worker-led campaign against a sub-standard national contract” with GE, organized in response to the “absence of leadership at the top of the union and no serious planning for a strike.”

As the opposition of IUE Local 201 members increased, even the local’s business manager, a member of the national negotiating committee, urged rejection of a 1979 tentative agreement. But, in the middle of this fight, the CP changed its position and supported the GE contract settlement it had previously deemed inadequate. When Emspak continued to campaign for a “No” vote, this had the helpful effect of demonstrating that his “loyalty was to the membership and not the international union or the CP.” Six years later, he reports, history repeated itself “when the Party endorsed union contracts with GE that Party members at GE had been leading the opposition against.” As Emspak recalls, “a top down decision was made, without input from many of us on the ground… At that point, there did not seem to be any benefit from being in the CP and most in the largest shop club in the industry simply left it.”

Law and Labor Education

Melrod and Emspak’s experience as rank-and-file activists helped shape their successful later careers in law and labor education respectively. As Melrod explains, even before deciding to go to law school, he had won seven National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) cases “forcing American Motors to reverse decisions punishing me for my organizing efforts.” One termination case dragged on for nearly three years before a federal circuit court of appeals ordered the company to re-instate him with full back pay and seniority rights. In other litigation, widely reported at the time, Melrod and two other rank-and-file newsletter editors were sued for $4 million in damages by AMC supervisors who claimed they had been defamed by Fighting Times. This company-backed effort to intimidate opposition caucus members also backfired. “The NLRB intervened after the civil trial, finding AMC guilty of violating our rights and ordering the company to pay over $300,000 in legal fees and lost wages.” As part of his later law practice, Melrod specialized in “refugee and asylum law, representing clients from all over the world fleeing political, sexual, religious, and ethnic persecution.

After he left GE and IUE Local 201 in 1987, Emspak transitioned first to state and federal jobs as a valued advisor to unions on the workplace impact of technological change. Then, he returned to his alma mater to teach shop stewards, local officers, and union staff members in labor education courses run by the University of Wisconsin School for Workers. During his career there, he founded Workers Independent News (WIN), which operated for sixteen years and, at its peak, produced pro-labor radio show content airing on 150 stations nationwide, which reached hundreds of thousands of listeners. In this new arena, Emspak found himself walking a familiar tightrope. During its existence, WIN raised several million dollars from twenty-two national unions, and additional donations from over one hundred local unions. But labor radio sponsors from the AFL-CIO and Change to Win affiliates were not always appreciative of “independent” reporting on their own strikes, contract campaigns, or internal politics. As WIN’s founder reports, “we faced pressure to restrict our coverage to conform to the interests and opinions of union leadership…press freedom did not seem to be of particular concern.” The WIN experience leaves the question of how to finance independent labor journalism unanswered—but, in Emspak’s view, “points to developing a funding model that is widespread and not dependent on institutional union support.”

As writers today, the authors of Troublemaker and Fighting Times have no WIN-type need for self-censorship (and no longer risk being sued for defamation by a factory foreman!). Both Emspak and Melrod have penned candid, illuminating accounts of their past union and political activism, which will be very useful to younger radicals who share their belief that only working class organizing can change the balance of power between capital and labor.

Posted Labor, Left Politics, United States

About Author

Steve Early has been active in the union movement since 1972, as an organizer and journalist. He is the author of five books about labor or politics, mostly recently Our Veterans: Winners, Losers, Friends and Enemies on the New Terrain of Veterans Affairs from Duke University Press. He can be reached at [email protected].