by Arley Sorg

Clarkesworld

If you ask your favorite science fiction authors who their favorite science fiction author is, many of them will say: Eileen Gunn.

Eileen Gunn was born in Dorchester, MA. “I grew up partly in Quincy, Mass., south of Boston, and partly south of there in Norwell, in the remote ’burbs, where we lived in a house that was built in 1802 and had seven fireplaces and a tunnel and seaweed in the walls. I attended a regional high school near Quincy and escaped sometimes on Saturdays into Boston for Russian lessons in the mornings and hanging out in Harvard Square in the afternoons trying to look like Joan Baez.”

Gunn went to Catholic college Emmanuel and earned a BA in history with a minor in English. She began working as an advertising copywriter, then moved to California to pursue fiction writing. In 1976 she attended Clarion, after which she wrote and supported herself through her work in advertising. She worked as director of advertising and sales promotion at Microsoft in the mid-eighties, but ultimately left: the job demanded over one hundred hour work weeks, which got in the way of writing. In 1988 she joined the board of directors of the Clarion West Writers Workshop, and in 2001 began editing online magazine The Infinite Matrix, which ran until 2008.

Eileen Gunn’s debut publication was “What Are Friends For?” in the November 1978 issue of Amazing Stories. In 1981 she had “Contact” in anthology Proteus: Voices for the 80’s and in 1983 she had “Spring Conditions” in anthology Tales by Moonlight. Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine published Gunn’s “Stable Strategies for Middle Management” in their June 1988 issue, and “Computer Friendly” in their June 1989 issue—both stories were nominated for Hugo Awards.

By 2004 Gunn had produced enough material to put out her first collection: Stable Strategies and Others, published by Tachyon. The book included essays by William Gibson, Howard Waldrop, and Gunn herself; a poem by Michael Swanwick; an original novelette coauthored with Leslie What called “Nirvana High”; and an original short story, “Coming to Terms.” Not to mention a reprinted novelette coauthored by a total four people: “Green Fire” by Andy Duncan, Pat Murphy, Swanwick, and Gunn. The collection was a finalist for World Fantasy and Philip K. Dick awards and was short listed for the Otherwise Award (then called the Tiptree Award). “Coming to Terms” won a Nebula Award and “Nirvana High” was a Nebula finalist.

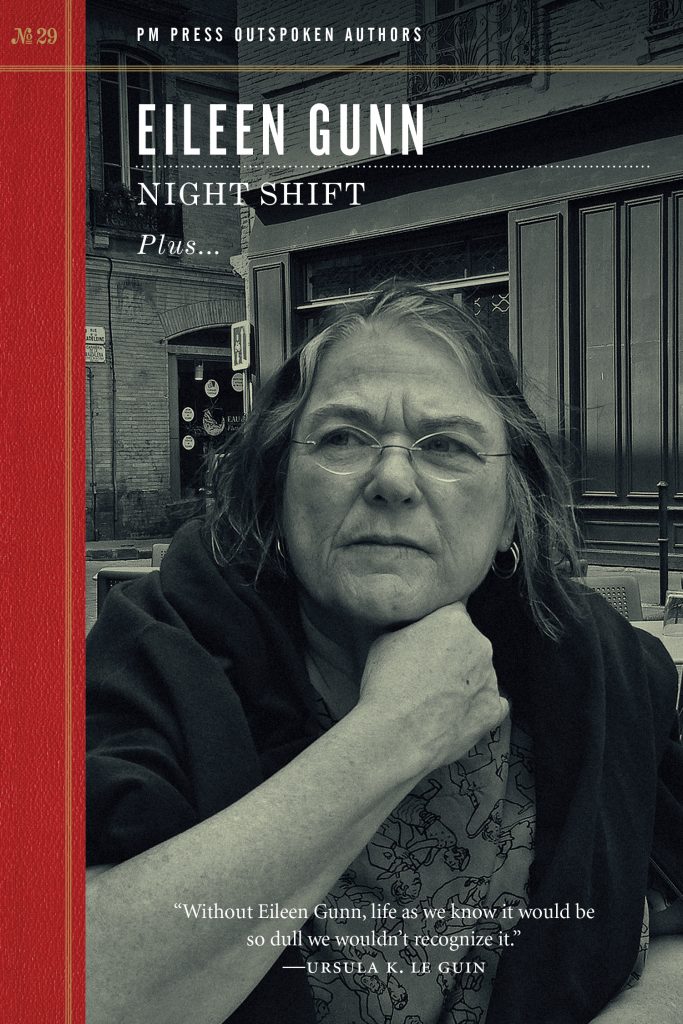

Tordotcom published Steampunk Quartet in 2011, which featured four short stories by Eileen Gunn that had run on the Tor.com website the year prior. In 2014 Small Beer Press published Gunn’s collection Questionable Practices, showcasing some of her work from 2006–2010, plus two original pieces. Her next collection is Night Shift due from PM Press in August.

Eileen Gunn lives in Seattle with her partner, typographer and book designer John D. Berry. “You can tell by the moss in our eyebrows.”

You were born in Dorchester, grew up south of Boston, and lived in New York and San Francisco. Have you lived anywhere else? If I recall correctly, you also had a memorable trip in Japan. Did you have any other memorable or interesting trips?

When I was in college, I lived in Brookline for a couple years, then beat it as fast as my little legs could carry me across the Charles to Cambridge, which I loved dearly, with its elderly houses and lumpy brick sidewalks and Socialist city government. I lived all over central Cambridge: Harvard Square, Central Square, Inman Square, Harvard Square again, Central Square again—every time the rent went up ten dollars, I’d move.

Then, after all the fun went out of Cambridge, I moved to LA’s urban sprawl—to La Verne, actually, in the San Gabriel Valley, where I was going to write, far from the financial temptations of Boston advertising. From there I went to Clarion in East Lansing, Michigan, then moved back for six months to the Boston area, where they kept all the freelance jobs in orange crates out on Rte. 128. I returned to LA briefly, then moved up to Eugene, Oregon, where some of my Clarion buddies and our benign deities Kate Wilhelm and Damon Knight lived. Then I fell in love with this dude who lived in Seattle, and I callously abandoned Eugene and all its sci-fi writers and tie-dyed splendor.

Turns out there was a tech industry starting up in Seattle, and I wandered into a job at a little company across the lake. After we’d been in Seattle for far too long, John was offered a job editing an iconic New York graphic design magazine, U&lc, and we moved to Brooklyn, where I was managing editor for GORP.com, then the world’s largest website about outdoor recreation. (And it wuz big.) When New York was enuf, we moved to San Francisco, and lived in Ellen Klages’ house on Bernal Heights for a couple years while she hunkered down in Cleveland. We moved back to Seattle, intending to sell our house here and move to the Bay Area, but that was twenty years ago: inertia has set in.

In addition to living all over the East and West coasts, I’ve traveled a lot, mostly out of curiosity. In 1973, I spent a month visiting friends in Japan and traveling on Honshu, and then took the Trans-Siberian Railway to Moscow, stopping off at cities across Siberia, then went on to Leningrad and Finland and made my way back across Europe to London and Madrid and back to Boston, where I was chief copywriter at a tech ad agency. I kind of wondered if I’d have a job when I got back, after two and a half months, but my employer was pathetically happy to see me (which was almost a disappointment).

I’ve traveled around Western Europe and the British Isles, plus at least four trips to Italy, three trips to Russia, to China and Japan a couple times each, to Mexico and Canada a bunch of times, Peru, Brazil, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Armenia, Australia, what am I leaving out? Iceland, Poland, Czech Republic. But the world’s a big place, and I’ve never been to India or Southeast Asia (though I worked for an Indian software company in Silicon Valley and hoped they’d send me to Bangalore or Chennai). I’ve never been to Africa or the Middle East. One place I’d really like to visit is Haida Gwaii, off the coast of British Columbia, which isn’t very far away, really, but not so easy to just pop over to see. They are closed to visitors during the pandemic. Wise move.

My favorite way to travel is to just go somewhere, by myself or with one other person, without having a schedule or reservations or anything but a rough idea of where I’m going. It helps to have some idea of one the local languages or to know someone there.

Do you have any hobbies or interesting projects that aren’t writing/publishing things?

I don’t have hobbies per se, but I have a lot of interests. I used to work in a Japanese antique store, and I’m interested in Japanese textiles and art and food and ghosts and yōkai. I like music, all different kinds of music, although I have rather exacting tastes, and I used to play guitar and lute. I like languages, and try to keep up with the six or seven I’ve studied, but generally I read them better than I speak them. I am not a polyglot, and Mandarin is giving me a real hard time.

I used to cross-country ski and hike a bit, but that’s fallen off as I’ve gotten older. (Creak.) When I lived in LA, I used to x-c ski up (and eventually down) the fire roads on Mount Baldy, by my lonesome on the ungroomed, untrampled snow, without bothering to tell anyone where I was going. This was long before cell phones. What was I thinking?

IIRC, I thought that if I didn’t come back from my outing, my housemate would eventually notice, and would figure I must be in the mountains because my skis were gone, and would notify the Forest Service, who would find my car at a remote trailhead and see my ski tracks going up the mountain. Eventually, I assumed, they would follow my tracks and see where I went off the side of the mountain, and, looking down five hundred feet, notice me below, waving my hat. Fortunately, it never came to that.

When did you start reading or even more specifically, start reading genre? What were some of the earliest genre books that were important to you?

Both my parents were artists, and I was raised to be the writer in the family. I could read before I started first grade. When I was seven, my second-grade teacher, to shut me up, gave me a 1923 copy of Peter and Wendy, Retold for Young People, and I thought it was the funniest book in the world. (I still think it’s a lot funnier than Barrie’s own novelization of his play.)

I read Alice in Wonderland when I was eight and memorized most of the poems. I think my first real genre books were juveniles by Alan Nourse, but my real fondness for science fiction came when I was maybe twelve or thirteen, and I started babysitting for families that read lots of SF. I read Heinlein, Asimov, Clark, Sheckley, Simak, Blish, Davidson, Fredric Brown, Damon Knight, Jack Finney, short-story collections, everything I could get my hands on, all while earning fifty cents an hour.

I read Heinlein’s The Puppet Masters in its entirety one New Year’s Eve in an unfamiliar house with clunking nocturnal sounds, semi-terrified, and grossed out by aliens that attached themselves to human backs like abalone, while my young charge slept peacefully in her bed. The lady of that house had huge stacks of sci-fi paperbacks in the living room, and lent them out to me generously; our small-town library had a good selection as well. There was no such thing as the Internet.

Did you start selling fiction right away, when you started sending it out? Or was there a struggle to land your first sale?

Other than three stories that appeared in my college literary magazine, I didn’t really write any fiction until just before I went to Clarion. I had thought I was going to be a music journalist, but I accidentally became an advertising writer, and then was too busy working and having adventures to write fiction. My excuse: it was the sixties.

My first sale was actually the first story I’d written since college, my Clarion submission story, “What Are Friends For?” It dutifully made the rounds of the major magazines of the day, but it had too many dirty words in it to be saleable to most of the magazines—that’s what the editors said, anyway. It sold to Ted White at Amazing Stories, who wasn’t afraid of dirty words. It appeared at the end of August, 1978, two years after I’d finished Clarion and eleven years after I’d finished college. I never got an actual acceptance: it just appeared in the magazine, and a friend saw it and let me know I was now a published author.

As it happened, the publisher of Amazing (who was not Ted) was well-known in the field for not paying promptly—and sometimes not paying at all—so I wasn’t expecting to see the money quickly, but it arrived a couple months later, in somebody else’s stamped, self-addressed envelope, with their name and address crossed out and mine written in. I took it to Kate and Damon’s monthly workshop to show it off, and Kate said, “He paid you? That bastard still owes me for a story I sold him three years ago.”

Anything else you want to add that you think might be helpful or interesting is great, or any little tidbits like hobbies, recent or meaningful experiences, and so on.

The single most important thing I’ve ever done for my writing was attending Clarion in 1976. It didn’t actually get me to write faster, nor did it immediately teach me to write better, but it gave me a context within which to write fiction. It yielded supportive friendships that have lasted all my life and, thanks to my teachers Kate Wilhelm, Damon Knight, and Joe and Gay Haldeman, introduced me to a community of writers who nurtured and challenged me, who made me part of the fabric of science fiction as it was woven in the seventies and eighties.

There is now Clarion and Clarion West and a network of similar workshops available online and in real life, and I’ve devoted a good bit of my time over the years to teaching and workshopping, and I still do both. I especially try to encourage writers who write outside the boxes, outside the categories, outside the memes and themes, because if you do that, it’s easy to think you’re doing it wrong, and wasting your time. I also want to encourage writers who love adventure and plot and all the sci-fi clichés, because that’s where the energy in our field comes from and that’s how many young readers and writers first become interested in SF.

In that context, I also want to mention and encourage Locus, whose mission has changed with the times, and I think now serves both writers and readers of SF. The magazine has blossomed in the past few years, widening its scope and interests as the field has changed and expanded. I know you’ve been part of that, Arley.

NB: I served for twenty-two years on the board of Clarion West and have been on the board of the Locus Foundation for something like fifteen years.

You were an editor at magazine The Infinite Matrix for several years. Did editing the magazine change anything about the way you write, or about your views of the industry?

Well, for six years I was both the publisher and the editor at The Infinite Matrix, so I learned far more than I wanted to about how small magazines are edited and what they need to do to survive. I learned that editors are not sitting in the catbird seat, slapping aesthetic judgments on hapless writers—they are, on a monthly basis, sometimes desperately, trying to find stories that make their magazine what they want it to be. I learned that publishers of small magazines that don’t fit into a recognized advertising category are constantly trying to find the money they need to keep the magazines afloat. I had previously been managing editor of a large, successful nonfiction website, and editing The Infinite Matrix gave me much more sympathy for both editors and publishers of fiction magazines. I don’t think it changed how I write or what I write, but it changed how I think about rejection: it’s not personal anymore. “Your story does not meet our needs” is the absolute truth.

I also learned that the editor isn’t the only one who deserves credit for running a magazine. Underground comix artists Paul Mavrides and Jay Kinney established the graphic look and feel. Nisi Shawl read slush, handled PR, and helped in many clever ways. Rachel Holmen contributed enormously by keeping us buttoned up legally and financially. I could not have done without any of them.

What is your process for writing short stories?

Process. Hmmm. My stories tend to start with a voice, and the voice evolves into a character, and the character delineates the setting. Plot is entirely separate from that process. I might have a vague sense of a plot or a premise before I start writing, but until I have a voice, I am lost. Once I have a voice, I salt the plot in liberally and keep poking it with a lit torch until it behaves.

I used to have a terrible process: I would flog myself until I got an idea, and then I’d flog myself until I’d written the story, and then I’d flog myself about how inadequate the story was. Now I don’t beat myself up: I just tell myself that nobody will ever read this story, so I can write it any way I want.

How would you describe your writing style?

I think I write in a number of different styles, depending on the mood of the story, the voice of the character, the time in which it’s set, etc. However, I consistently make certain choices as I write, and as I edit my own work: I like short sentences, direct verbs, and few adjectives. I eschew periphrasis. All that may derive from my having spent my formative years writing advertising for technology companies. I usually think that the reader has more important things to do than read my precious prose, so I should be quick, funny, and smart.

My ideal length is two hundred and eighty characters, the length of a tweet. This used to discourage me from longer forms, but now I’m thinking of a novel as merely four thousand consecutive tweets.

Your first short story came out in 1978 in Amazing Stories. You’ve been a well-respected writer for a long time, but you didn’t necessarily publish that often. Things picked up around 2007, and then picked up even more in the 2010s. What changed?

Well, that’s a sharp question: I’d never thought of it that way. The key year to look at, I think, is 2004, because there can be a three-year gap between starting a story and getting it published. What changed in 2004 was that by then I had enough money stashed away that I didn’t have to work full time. My day jobs had involved writing well on deadline and were pretty stressful, so they used up my writing energy. Gardner Dozois had told me many times that I should quit my job and starve to death like a respectable writer, but it took me twenty years to take his advice.

Another unusual event that happened in 2004 was that Jacob Weisman, at Tachyon Publications, persuaded me to let him publish my first short-story collection, Stable Strategies and Others. Jacob didn’t listen to my protests that I didn’t have enough stories for a collection, and he pushed me to pull it together. It was very well received, which encouraged me to write faster, and I’ll be eternally grateful.

Those two events in 2004 made me look a lot more productive in 2007. After that, Michael Swanwick suggested that we collaborate on a story, and he painstakingly schooled me on how to grab a story by the scruff of the neck and shake it until its meaning appeared. He was amazingly patient, and we wrote four stories together, each one better than the last. Then he gave me an idea for a short story to write on my own. “You can do this in three months,” he said. I realized it was a novel, not a short story, and I’ve been working on it ever since. It’s a big, scary idea, and I think I can do it justice. Since it’s Michael’s idea at heart, I have full confidence in it.

In 2014, my second collection, Questionable Practices, came out from Small Beer Press, and that also perked up my spirits and made me more productive.

You mention working on a novel in your 2014 Locus interview. Tell us about the novel-in-progress: is it still in progress? How is it going? And what do you enjoy most about it?

The novel is evolving, but I’m not sure whether the process by which it’s evolving is one of phyletic gradualism or punctuated equilibrium. It moves in dips and starts, like MacGillycuddy’s Reeks.

It’s an alternate history set in slavery times and after, and I have had a lot to learn in order to feel confident enough to write it. Slavery time in the US was a constant, personal war of terror against the Black people who lived here, a war that continued after slavery ended and is carried on this very day, every day. Initially, this was an overwhelming topic to take on, but it is the original sin of America and cannot be avoided. The characters’ voices are always key to me: they say things that surprise me, which is what satisfies me most. They seem to know more than I do. I also enjoy deep-diving into American and Canadian history, hearing people from the past who seem to be speaking directly to me, and finding startling coincidences between the exigencies of plot and the things that actually happened. I enjoy the license writing gives me to leap into every rabbit hole, and I keep finding rabbits.

In your new collection, title story “Night Shift” foregrounds a discussion of life and consciousness, comparing the artificial to the organic in several ways. It also folds into the narrative ideas about the impact of technology on economy, social hierarchies, and more. What were your biggest inspirations for this piece and its characters?

The biggest inspiration for the story was being invited to contribute to an anthology, Visions, Ventures, Escape Velocities, being put together by NASA and the Center for Science and the Imagination at Arizona State University. SF writers were to partner with NASA scientists to create fiction that would attract younger readers to science and technology. I was asked to write about asteroid mining as it would be taking place in about 2030, and I very quickly determined, using common sense methods alone, that there would be no hilariously inept miners scooting about from asteroid to asteroid on two-man rocket ships: robots and AIs would have all the fun.

NASA itself was a source of inspiration. When I started the story, they had plans to send a probe out to grab a sample of a tiny near-earth asteroid named Bennu, which is considered, of all the known objects in the solar system, one of the most hazardous to Earth. Bennu transects Earth’s orbit and could possibly smash into us on September 24, 2182. I kind of fell in love with hapless but threatening Bennu and I posited that NASA might later send a second probe to take it apart, thus protecting Earth and at the same time acquiring building materials for a space station. Since I finished the story, the probe, OSIRIS-REx, has gone to Bennu and sent back pix and all kinds of fascinating information. It’s headed home with a few small rocks, and will arrive, if all goes well, in 2023. (I can hardly wait.) NASA has already scheduled OSIRIS-REx for another adventure.

Another inspiration was slime molds, simply because I love slime molds. They move efficiently and seem to plan things out collectively, even though they have no brains. So, as my science-fictional contribution to asteroid mining, I posited a harvesting technology based on how a slime mold might devour a blob of oatmeal.

In addition, I think there are too few Pacific Islanders in science-fiction stories, so my protagonist is a young Samoan-American engineering student working the night shift. (Disney’s Moana came out a little later, for better or worse.)

That’s a lot of inspiration per square foot, but it took all of these things coming together in my head to make the story jell.

There’s this potential to veer into horror with “Night Shift,” and a few hints at the possibilities of disaster. Did you consider other directions or play with different endings, or would disaster and horror have undermined the intended themes?

Oh, yes, there could have been much more to the story. At one point, I considered a subplot that linked the protagonist’s slime-mold pets and the human-curious AI. It had a certain thematic coherence but veered into pseudoscience territory, so I axed it. I might someday write another slime-mold story, because they are strange and fascinating creatures. For example, slime molds communicate with one another by releasing gaseous chemicals into the air: by farting. How could I not put that in a story at some point?

The most recent story in this collection is “Terrible Trudy on the Lam,” originally appearing in Asimov’s in 2019. What was your inspiration for this story and how did it develop?

I was introduced to Terrible Trudy in a tweet from Karen Joy Fowler, retweeted by Kelly Link. It linked to a charming essay about the tapir escape artist who repeatedly fled the San Diego Zoo in the 1940s. In one incident, she was gone for eight days in the middle of San Diego with the entire city looking for her. In her tweet, Karen wondered what Trudy did when she was out on the town.

I suggested to Kelly that perhaps the tapir, during one of her escapes, became a girl detective, and maybe Kelly could write that story. But Kelly demurred, and I had to write it myself. Alone in the 1940s, I watched Ginger Rogers roller-skate, free-associated on Jimmy Durante, leap-frogged to Firrup Mumble, and the story practically wrote itself, except for the part where I had to figure out what it all meant.

PS: Neither Karen nor Kelly has any recollection of this, which is probably for the best.

Thinking on the stories in this collection, do you see an underlying theme? Or an overarching one?

That’s a hard one. I try to do something different with every story, and I usually don’t know what a story is about until after it’s finished, sometimes until years after it’s finished. Often enough, what I think it’s about is not what other people think it’s about—and I have no reason to believe that the other people are wrong. There are some characteristics the stories have in common: they are all about people (and animals) who are a bit lonely and a bit optimistic, and are thrown on their own resources. All of them—people, animals, AIs, and slime molds—are trying to communicate with others, sometimes others of their own species and sometimes not. They seem to come to different conclusions about whether it’s worth the effort.

Me, I usually think it’s worth the effort, and that’s why I write stories: to communicate something ineffable, something beyond plot and character, beyond the futures and the fantasy worlds, that can’t actually be delineated, can’t be extracted from the story, can’t be defined. I have to write the story to know what it is all about, and readers have to read it to know.

Looking at your ISFDB page, you’ve published nearly as much nonfiction as you have fiction. What, for you, is the key to crafting excellent nonfiction?

Point-of-view and determination. Sometimes I don’t know my point of view on a subject until I’ve written a substantial amount, and I have to go back and revise what I had written previously. Writing about actual people is hard, because people are complex, and you cannot really define another person, no matter how many words you write. Writing about events, ditto. Even physical things are hard to write about: the thing is not its description or even its provenance—about as close as you can get to a thing is writing about what it means to you, and I guess that’s true of people and events as well.

Are there important similarities and differences between this book and your earlier collections?

Well, this collection includes both short stories and personal essays, rather than just stories. The stories are all my most recent uncollected work, and the essays are about five writers who have had a significant effect on me: Ursula K. Le Guin, Joanna Russ, Gardner Dozois, Carol Emshwiller, and the poet JT Stewart.

Night Shift is part of the Outspoken Authors series from PM Press, edited by the protean Terry Bisson, and it joins a long, desultory conversation among writers who don’t necessarily know they are talking to one another. PM Press is a mind-bendingly awesome publisher that specializes in books on a wide range of fascinating subjects covering radical thought and radical history: activism, philosophy, comics, sexuality, and music, and lots more.

I don’t mean to slight either of my other awesome publishers, Tachyon Publications and Small Beer Press, who are rightly revered by writers and readers and me—the mind-bending part of PM Press is the terrain-gobbling range of their commitment to radical thinking, and I’m proud to be included.

You have coauthored a number of short stories over the years. What are the important factors to successfully coauthoring shorter pieces? And, if you had to pick one, which of your coauthored short stories should people read?

I wouldn’t say that all happy collaborations are the same, but I’m willing to bet that each of the unhappy ones is different in its own way. There are many things that can go wrong and many ways to recover. In some ways, it’s like wrestling: it’s good to have established rules at the beginning about what’s fair and what’s not to be tolerated.

In other ways, it’s like a business partnership, in which the partners had better be ready to make trade-offs, on the fly, for the success of the enterprise. And sometimes it’s like a marriage: the collaborators don’t necessarily know what they are getting into, things might get difficult for a while, and yet, if everyone perseveres, the relationship can result in an adorable outcome that neither partner could have produced alone.

As for suggesting a collaboration of mine that people “should” read—ha, ha, I’m not falling into that trap. It’s like asking me to pick a favorite child. Each was born in fire and blood and laughter, and alas none of them are in Night Shift. Readers who are mad for collaborations should check out my previous collections.

You have written about Joanna Russ and Carol Emshwiller, authors who are deeply beloved by readers who know them, but who are far less known than Gardner Dozois or Ursula K. Le Guin. If folks who haven’t read them looked at one work by each author, which work should it be, and why?

Just one? Unfair! Can’t do it! Won’t!

But I can offer simple choices.

Of Carol Emshwiller’s novels, I’d choose Carmen Dog or The Mount. Of her short story collections, I Live with You is in print, and it’s wonderful.

Joanna Russ is even harder to characterize. The Female Man is her best-known work, and it’s sharp and funny and relevant. Start with that, or with And Chaos Died. You can sample them for free on Amazon.com.

And, by the way, Gardner R. Dozois was a superb writer as well as a legendary editor, and his work not as well-known as it ought to be. I recommend his collection Strange Days, which includes many wonderful stories and his novel Strangers.

What else are you working on, what do you have coming up that readers should know about?

Funny you should ask—as it happens, I have a ghost story, “One Night Stand,” scheduled for the September/October issue of Asimov’s Science Fiction, which should be available in late August. In the non-fiction department, my essay “Does the Edge Still Bleed?”, on reading William Gibson’s Neuromancer forty years after it was written, is available online at Tor.com, and will be published in 2022 as the introduction to a new edition of Neuromancer from Centipede Press.