By Cindy O. Herman

The Daily Item

August 15th, 2022

If you were a coal miner in the early 1930s, with unemployment rates reaching to 50 percent and the coal company where you worked recently shut down, what would you do?

Thousands of men risked their lives to illegally work their own mines on company ground, a piece of anthracite-region history that until now has been overlooked.

Book tour schedule

Thursday, Aug. 18, Lewisburg, 7 p.m. at Himmelreich Memorial Library

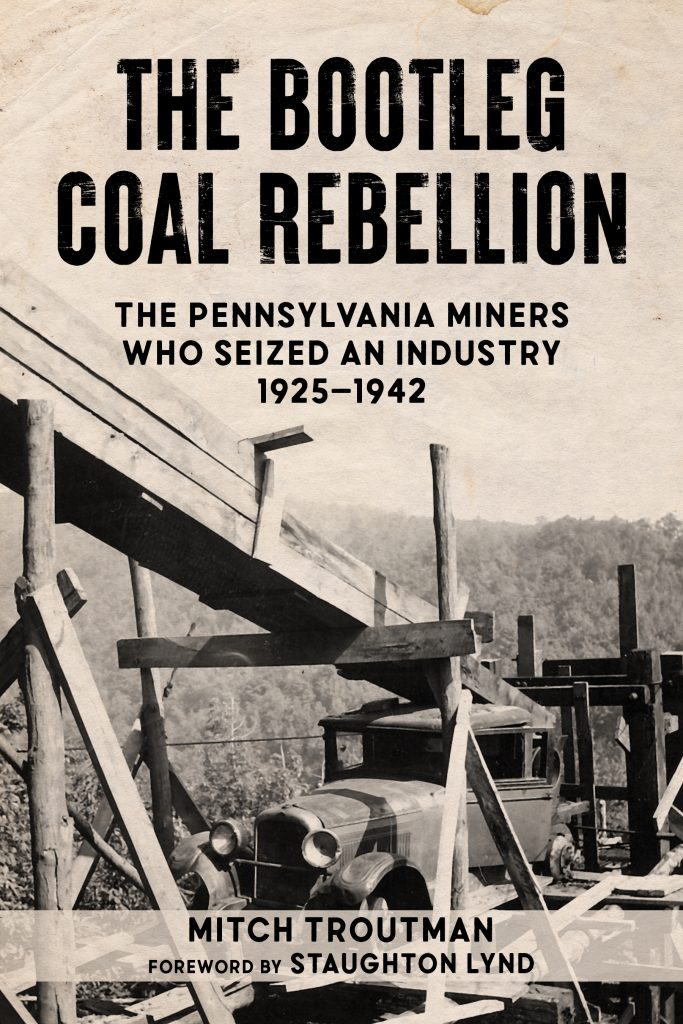

When Mitch Troutman, currently living in Pittsburgh, learned that he is a direct descendent of bootleg coal miners, his curiosity led to writing “The Bootleg Coal Rebellion,” published by PM Press.

“My great grandparents on both sides were bootleg miners (in Shamokin and Gowen City),” Troutman said. “But I didn’t know that until after I started writing the book. The photos I dug up sparked memories in my pappy before he died, and on the other side of my family I found ‘independent miner’ written on a draft card.”

“Something that’s so exciting about Mitch’s book is that it is telling a social history of our region, and one from not that long ago,” said Sarajane Snyder, who runs Mondragon Books, in Lewisburg. “The people in the book are the grandparents and great-grandparents of folks living their lives here today.”

Residents in coal mining towns accept the fact that areas of their town, and even their own backyards, sometimes sink gradually over time because beneath them are abandoned coal mines dug by men trying to heat their family’s home.

A quote on Troutman’s website, www.bootlegcoal.com, explains the attitude of the coal miners after the mines closed:

“We don’t know and we don’t care who’s supposed to own the land. God put that coal there — not the Philadelphia and Reading Coal Company.” The quote is attributed to Mike McCloskey, bootleg miner, Schuylkill County, 1935.

“Bootleggers mostly dug on company lands but really they’d dig anywhere. Some people have even discovered old coal holes sealed off in their basements,” Troutman said. “Hazards and subsidence come from all mining. A lot of coal holes (bootleg holes) weren’t properly sealed for years. Around Shamokin it was the infamous Clarence ‘Mooch’ Kashner who led a campaign to seal them years ago. But there were also old fan houses from the collieries, as well as land that collapsed into hollow mine breaches, leaving an exposed hole.”

Kashner, an independent miner and owner of Kashner Coal Company, was the president of the Independent Miners Breakermen and Truckers Association of Shamokin.

Eventually, after fending off half-hearted police raids for years, the bootleg coal miners organized. Ten thousand of them piled into trucks and traveled to Harrisburg to fight an anti-bootlegging bill in the mid-1930s.

“His book is a reminder that, even here in our backyards, people and communities have tremendous power when they can work together on a common cause,” Snyder said. “I commend him for finding a lead and following it through, creating a whole portrait of a momentous time in central PA.”

Troutman’s curiosity about bootleg coal miners led him to find answers to his growing list of questions.

“I wondered about the origins,” he said. “Why do people treat Reading Anthracite’s land like it belongs to everyone? Why are we the only place in the country that has small, family mines? Where did it all start? So I read where it was mentioned in other books and followed the sources. The big boon was finding a collection of cassette tape interviews with men who’d bootlegged during the Depression.”

The more he learned, the more he thought it was important that people in the area know the truth about our past, he said.

“If you’re from any Northumberland County coal town, chances are good that your family illegally mined during the Depression,” Troutman said. “When it came down to it, they decided property rights of the mine owners were trumped by the need and the will to survive.”

Along with stories of the bootleggers himself, “The Bootleg Coal Rebellion” is also a story of early labor unions, civil disobedience, equalization and Bootleg union meetings that “were loud, raucous affairs, where everyone got a say before votes were taken.”

“While the story of the bootleggers might be an extraordinary one, I think there are many more untold stories from our recent past,” Snyder said. “I hope this book encourages any young historians who might be interested in telling those stories to follow their heart and go for it.”

Cindy O. Herman lives in Snyder County. Email comments to her at [email protected]