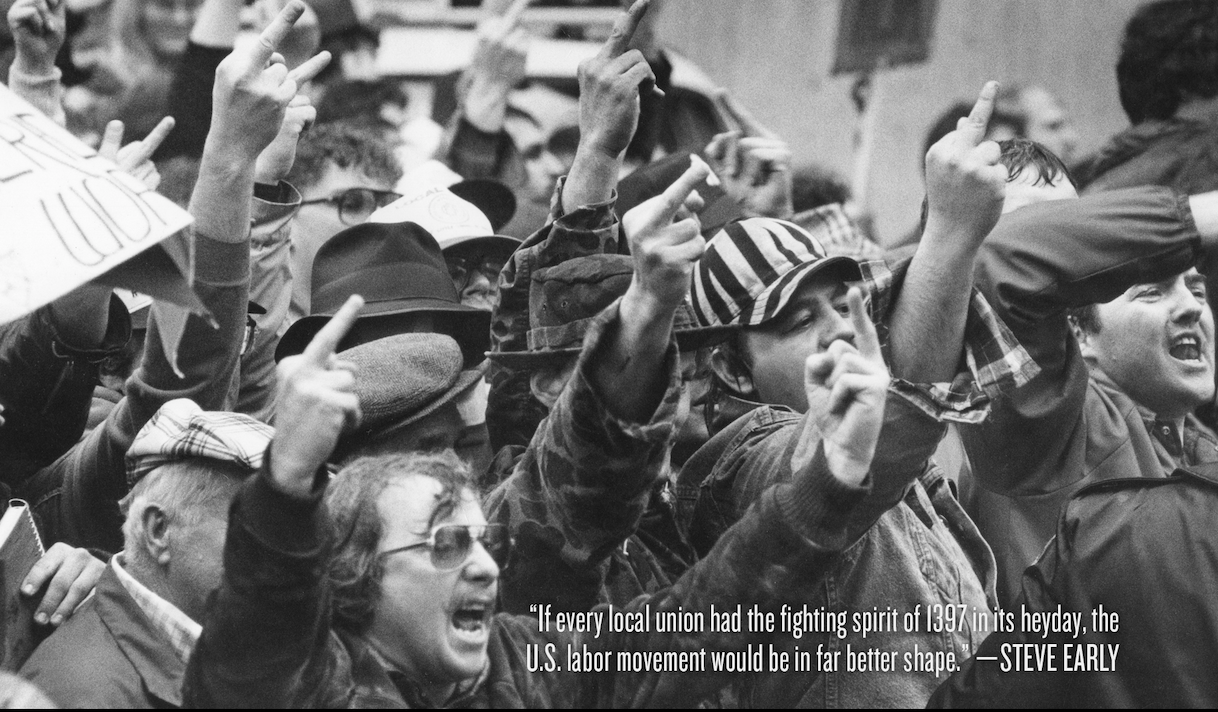

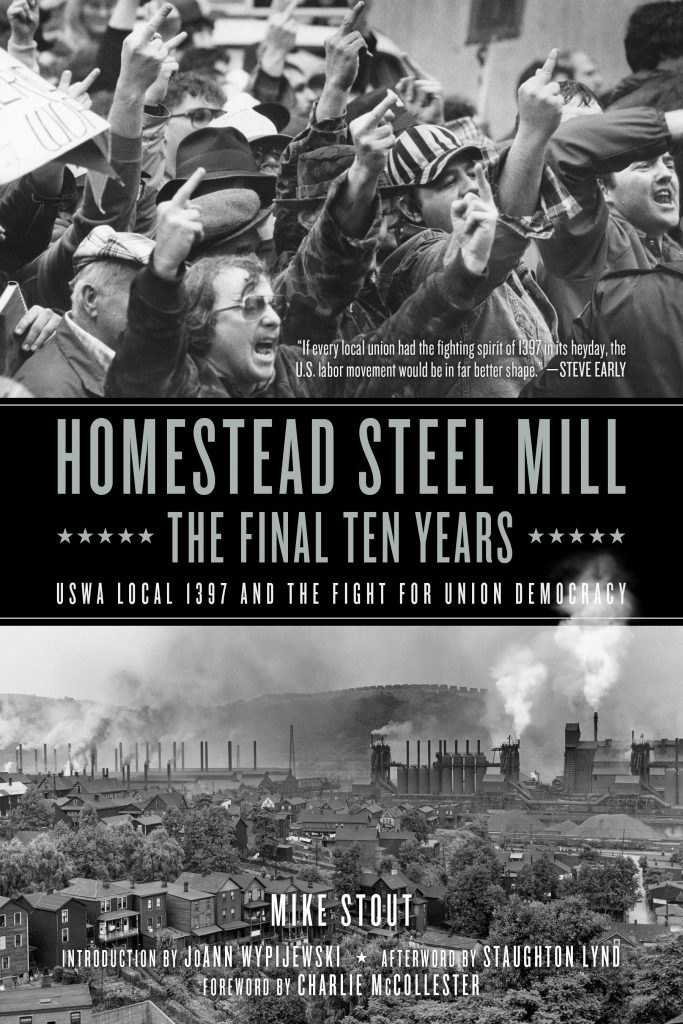

While attending the Labor Notes conference in June I picked up a copy of Mike Stout’s 2020 memoir, Homestead Steel Mill: The Final Ten Years (PM Press). The book’s subtitle, “USWA Local 1397 and the Fight for Union Democracy,” caught my interest as a long-term member of the Steelworkers Union.

The book describes experiences and fights in the 1970s and 1980s at U.S. Steel’s Homestead Mill and in USWA Local 1397. This is a story of the workplace, the building of a rank-and-file caucus in the Union, and the work to build community coalitions to save the steel mill and the western Pennsylvania town. The book documents some very important history and lessons for those who are working to form or reform unions whether they be at Starbucks or Amazon, if they participated in last year’s “striketober”, or just want to understand what might be possible in their workplace.

The story began in 1976 when three workers began talking about how things weren’t being addressed by the Union. One of those workers, Michele McMills describes it this way:

I had to walk three miles to the ladies’ room from my workplace, and it got to be a drag. So I went to the Union to see if I couldn’t get something done about it. But they weren’t really interested in fighting my case, so I started going to union meetings to see what was happening, and, heck, I don’t know, a couple years later, I figured I could do a better job. (pages 49-50)

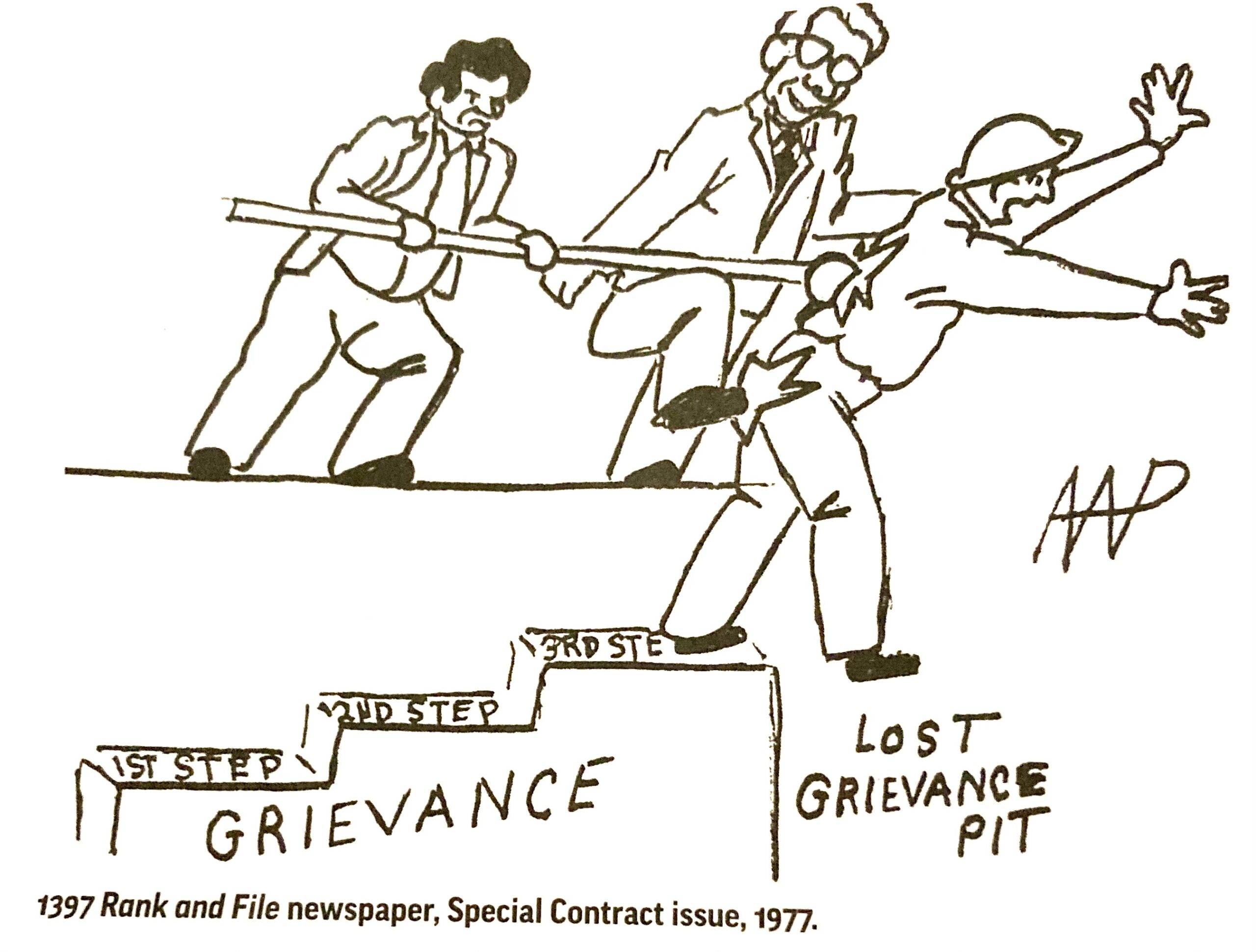

She, Ronnie Weisen, and John Ingersoll began to work together and started the “1397 Rank and File” newspaper. The newspaper was distributed throughout the plant, no mean feat in a plant that stretched over four miles and had more than 8000 people on the tools. The newspaper did two things exceedingly well: tell about conditions in the mill and demand the union does something about them. The very first issue included “Plant Plague,” a column that “allowed any worker who had a complaint or grievance to air it in the paper for all to see” (page 54) and discussed not being “able to find their grievance men” or “heard at union meetings because they are out of order. ” (page 55)

Members of the caucus worked hard and managed to build a fighting organization that, within three years, won the election for the leadership of the Local! At least one reviewer has called the book a page-turner. It is that, especially in this part. No worker is an abstraction; everyone is a live full human being. They have names and pictures; their stories leap out of the pages. Even the “old guard” leadership with whom the rank and file caucus did battle comes through as people. So much writing about labor, even by well-meaning scholars and activists, treats the workers only as part of a mass or a sociological category.

Taking office in 1979, they immediately worked to change the grievance procedure. No longer would a worker complain, hear “I’ll look into it,” and have their grievance fall into the “grievance pit.” Now when a grievance was filed, the Local used it as an organizing project. There was an absolute refusal to have side discussions. Workers gathered evidence and were brought into all steps of the grievance procedure to present that information. When it came time to go to arbitration, working members of the Local presented the arbitration. Under that kind of pressure and with that type of attention, the grievance procedure became a way to solve issues and a way to have people recognize their own power as workers.

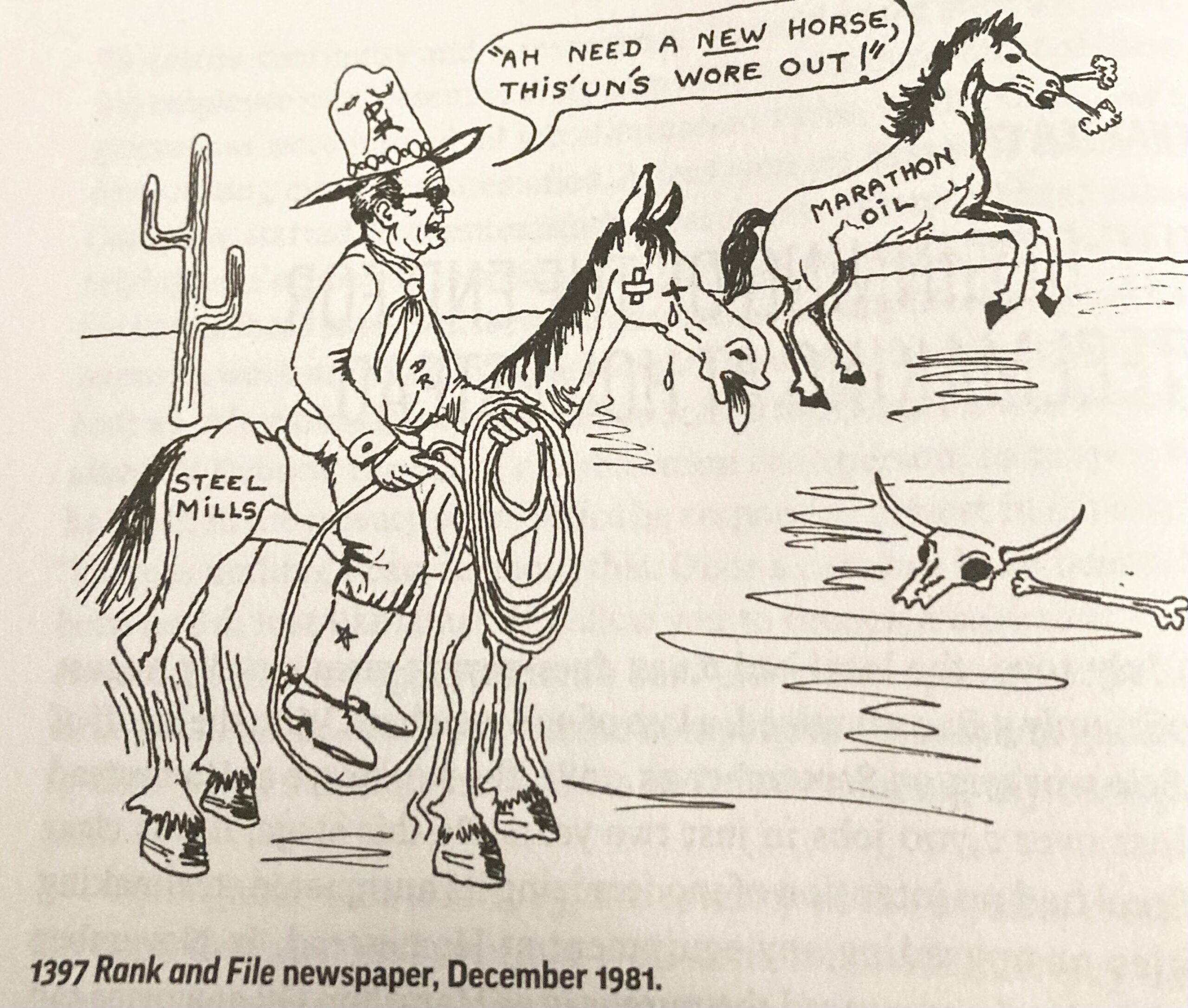

This is, sadly, not a “happily ever after story.” The steel industry in the U.S. was in trouble. It had refused and resisted modernizing the mills, especially the Homestead Mill. Instead of investing and modernizing the mills, U.S. Steel refused. Instead, they took their billions of dollars and diversified (even at one point buying Marathon Petroleum.) They began slowly closing parts of the mill over the next several years until nothing was left.

This most definitely is not a happy ending, but Local 1397 and the Caucus did not go quietly into the night. They fought and fought hard. They worked with Community organizations, did their own lobbying in Washington D.C., organized demonstrations, organized bank boycotts, organized food banks, and worked toward building the “Steel Valley Authority” (modeled on the Tennessee Valley Authority.) Sixteen laid-off workers who knew they were not likely to ever get their jobs back even walked into the plant and winterized some of the equipment so that when they saved the facility, the equipment would still work. Finally, they weathered a lockout in 1986. These actions and these fights were the workers’ idea of what needed to be done; they did not want to wait to find out what “effects bargaining” could get them. There were other actions and fights among the workers about what to do. Some things they did may not have been in their best interest in hindsight, but they were the workers’ ideas and their activities. The workers were told they did not have a right to tell the company how to run its business. Instead of accepting that, 1397 asked, along with workers throughout the steel industry, “why the hell not?”

Staughton Lynd, in his afterword, recommends this book be read “not just as a stirring story but as a manual in response to the question: What is to be done?” (page 293) In the decades since the events of this book, capitalism has continued to restructure, realign, and reshape itself over and over. I once heard a speaker refer to capitalists as a swarm of locusts stripping a field and moving on to the next field. This will remain the way things are until we can figure out, as workers, that we can tell the company how to run the workplaces we built. In fact, workers often know they need to tell their bosses how to run their business, but they are ignored by their leaders. The first step that I see in the many new fights to form or reform unions is to make sure that the workers’ ideas, actions, and voices are at the center.

[Editor’s note: Every issue of 1397 Rank and File included cartoons drawn by workers. They were equally sharp in their criticisms of bad decisions by the Company and the Union. The two cartoons featured in this article are included in the book.]

For more than fifty years, Mike Stout has been an antiwar, union, and community organizer, as well as the last Local 1397 Union Grievance Chair at the U.S. Steel Homestead Works. He is currently president of the Allegheny Chapter of the Izaak Walton League, the oldest environmental conservation organization in the United States. Stout is also a singer-songwriter and recording artist, with eighteen albums and more than 150 songs written and recorded, who has used his music to raise tens of thousands of dollars for a host of social and economic justice causes.