The Author of The High Sierra: A Love Story Talks to Daniel LoPilato

By Daniel LoPilato

LitHub

The Sierra Nevada mountain range rises high above the eastern boundary of California’s Central Valley. A rocky spine some four hundred miles long, its staggered peaks are wreathed with conifer forests and incised with deep glacial valleys. It is a wild landscape of granite cliffs, thundering waterfalls, rolling meadows, immense hardwoods, and cool alpine lakes.

Perhaps more than any other mountain chain in North America, the Sierra has a tendency to inspire fanatics—people who structure their entire lives as a recursive journey into its highest reaches. Accounts of their journeys can be found on online message boards, in published trail guides, in adventure narratives going back to the 19th century, and possibly even in the ancient pictographs and petroglyphs that still persist on Sierra granite.

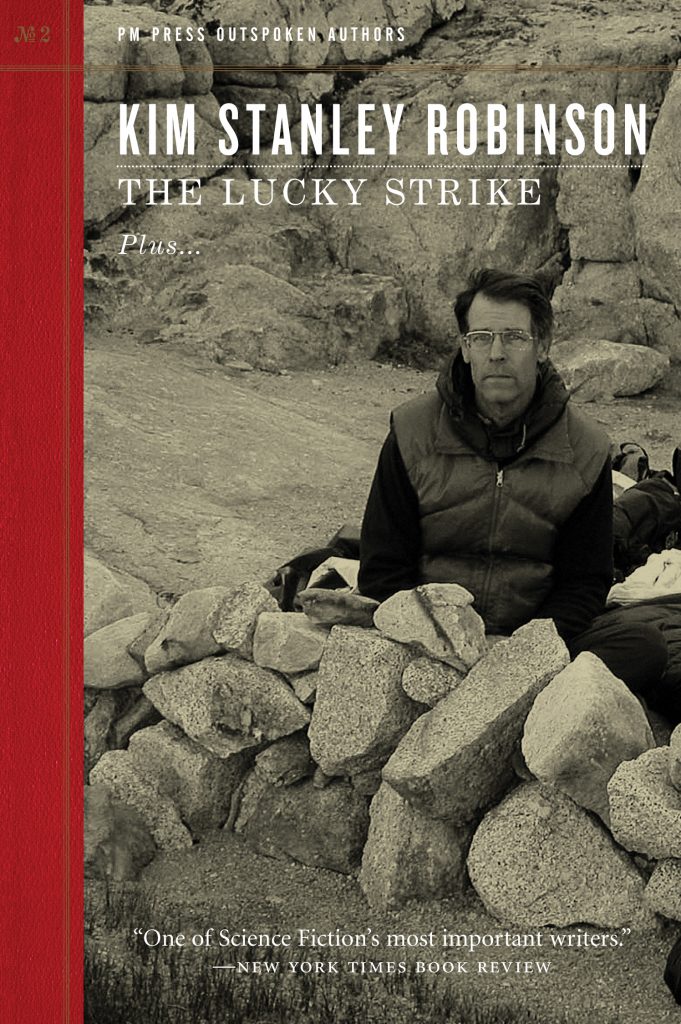

Among these Sierra fanatics is the celebrated sci-fi author Kim Stanley Robinson, who has spent much of his adult life backpacking in the Sierra Nevada. His latest book, The High Sierra: A Love Story, examines the range’s history and the author’s enduring love for the high country. It’s a deeply personal work representing a culmination of Robinson’s experience and reading, mixing gear advice and route-finding tips with stories from his life and from the history of the range. We recently chatted about the book and what we can learn from other Sierra fanatics.

*

Daniel LoPilato: In the past, you’ve discussed the influence of the Sierra Nevada on your novels and your ambition to write nonfiction about the range. The result is a potent mixture of memoir, history, travel guide, geology, and criticism. Why did you choose to write this book now, and how did it come to take this form?

Kim Stanley Robinson: A confluence of factors made it the right time to write this book. I’ve wanted to write it for decades, and was a little scared I might never get to it; then I came to the end of my contractual obligation to my wonderful publisher Orbit Books; also, The Ministry for the Future represented a kind of summa for my climate fiction, and as such a pause point; and lastly, the pandemic had me staying home with lots of time to write. So I started the Sierra book in spring 2020, and it poured out of me.

As to its form, I had a lot of different topics I wanted to cover, and I finally decided it was best to destrand them and take them one topic at a time, then braiding them together into a kind of tapestry. It just seemed the best form for the content I had in mind.

DL: This book helped me to see more clearly a connection between nature writing and science fiction, both of which replicate worlds and landscapes with a high degree of fidelity. Since your novels are heavily researched, I wonder if you draw a firm distinction between writing about places that are principally “real” and places that are principally imagined. How does writing about a world you can walk out and see affect your approach to a project?

KSR: An interesting question. For completely imagined landscapes, as for instance my fictional moon Aurora in the novel of that name, I could only work by analogy to landscapes on Earth, or in the solar system. There’s nothing I can do in the way of research in cases like that, it’s just a matter of plausibility.

Humans have been in every landscape forever, yes, and should be allowed to visit everywhere and anywhere.

Then for a place like Mars, we have—since the Viking missions of 1976—been given an immense new amount of data about that place, which we didn’t have before. It was possible when I wrote my Mars trilogy to read much of that new information and try to incorporate it into the descriptions in the book. It was much the same for the rest of the solar system, when I wrote 2312.

But then when writing about the Sierra, and also I should add Antarctica, and in my California novels, it’s been possible for me to walk on the land and sit with the living communities on that land (not very robust communities in Antarctica, of course), and write out of my own perceptions. I can write what I’ve seen and felt, and that has been a real pleasure.

DL: I’m a fan of trip reports published online by other backpackers, and it sounds like you are too. These reports convey a tremendous amount of information about trail conditions, route-finding, campsites, water sources, and the fate of the writer’s newest piece of gear. I read The High Sierra: A Love Story in part as a contribution to this informal body of writing. Are trip reports part of your writing process, and do you keep a writing routine in the backcountry?

KSR: Online trip reports by the Sierra community are a lot of fun and often inspirational. My trip reports are private and sporadic, and I haven’t done them for years; they were mainly for my own memory, and to amuse my friends who had been on the trips as well, so there was no real reason to write them. I do usually keep a daily report, written on the backs of the topo maps used on the trips, but these are just a couple lines per day.

I’ve also written some poems up there as kind of a “Buddhist daily” to mark impressions from the day; these are also on the backs of maps. When I was young I wrote a fair bit while in the Sierra; now older, I go up there in part to get away from writing.

I have to say, many nights in the Sierra, my writing would be things like “cold, hungry, tired,” and the next day, “tired, cold, hungry,” so it isn’t really the right time to write, I guess.