Fighting Times provides a vivid group portrait of the men and women who joined with him in the day-to-day struggles to better their own lives and to better the lives of their family members and communities.

By Jonah Raskin

Portside

his new memoir about years of turbulent life in American factories brings to mind The Organizer, a 1963 Italian movie in which a penniless organizer, known as “the professor”, appears in Turin at the end of the nineteenth century in response to a plea from desperate railroad workers.

No one in any factory called Jon Melrod “Professor,” but as a labor history major at the University of Wisconsin, he studied the history of working-class struggle and organization in the US. Years later, as an in-plant organizer, he created a seven-week Labor School designed for rank-and-file union members and shop stewards. Marcello Mastroianni’s Professor Sinigaglia would recognize Melrod as a comrade and as a brother-in-arms. Both were outsiders. Both became insiders, and both changed the political battle they joined and were in turn changed by it before they moved on.

Melrod was an unusual organizer, which makes his story all the more valuable. College students and members of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) who became working class organizers numbered in the thousands. Melrod sets out to write the history of just one of them, and his story is a valuable insight into the determination and accomplishments of those who went into industry to continue organizing for revolutionary change after leaving the college campus.

Melrod’s working class memoir takes place mostly in the industrial American heartland, from the early 1970s to the mid 1980s, in the aftermath of the Long Sixties, when people of color, students, workers, feminists and writers the world over joined revolutionary movements. Melrod organized in Milwaukee, Racine and Kenosha, Wisconsin, which labor journalist Steve Early describes as “the scene of intense shop floor campaigns against racism and for militant unionism in the auto industry.”

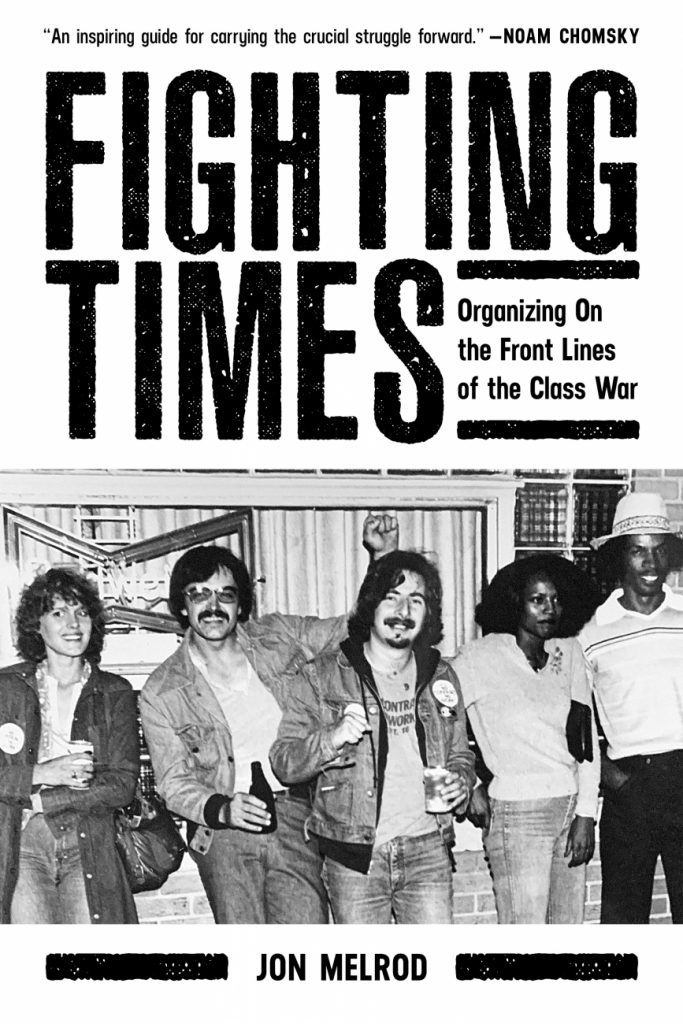

Fighting Times, named for the “shop paper” produced by Melrod and his comrades, offers an unsentimental portrait of one man who gave unstintingly of himself in the cause of labor, and nearly lost his life because of exposure to toxic chemicals.

“Little did I realize that the choice I made then—to take factory jobs to organize workers in those plants get the justice they deserved —might end up killing me decades later due to pancreatic cancer,” Melrod writes near the start of a story in which he is almost always at the center of the action, and yet never self-serving.

“I had to learn not to go it alone or play the hero,“ he explains. Still, for years he performed heroic work. “I steadily moved up in United Auto Workers (UAW) leadership,” he explains. “I held the positions of line steward, department chair, education committee member, chief steward, international union delegate, and eventually was elected to a top position on the executive board/bargaining committee.”

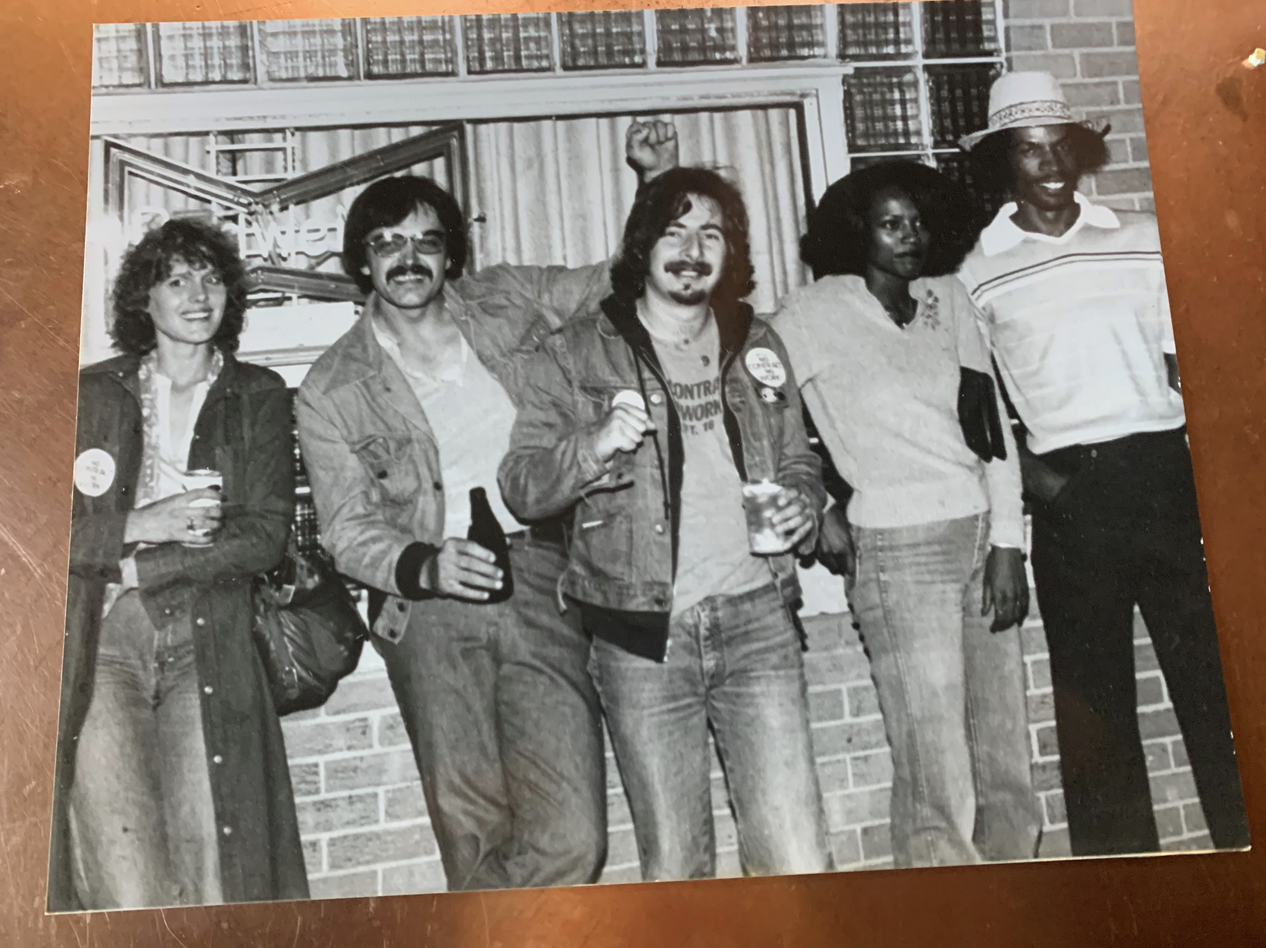

While Fighting Times focuses on Melrod, it also provides a vivid group portrait of the men and women who joined with him in the day-to-day struggles to better their own lives and to better the lives of their family members and communities. Bad guys aplenty also appear in this narrative, some of them “goons and ginks and company finks”— to borrow a phrase from Woody Guthrie’s 1940s ballad “Union Maid” — who aimed to bust unions. Melrod’s goal was to build a powerful fighting organization, create working class solidarity and to use every weapon at the union’s disposal— leaflets, newspapers, picket lines, slowdowns, strikes, buttons, and bullhorns. Everything and anything to amplify, spread and deepen the message and the struggle against management, among others, that unions must be rooted in militant class struggle and be willing to throw down to take on the bosses.

Melrod’s goals, he explains, were “unity,” “transparency,” “militancy,” “inclusivity” and “taking up the vitally important issues of race and sex discrimination, anti-Semitism on the job and redneck bias.” Reading between the lines, a young organizer in the US today would have a good idea how to operate—learn everyone’s name and individual story, for example—and what pitfalls to avoid, like hot headedness and the impulse to tell foes to “fuck off” and walk away. “Better to go back in, consolidate gains, and build on the advances.”

“When you first go into a shop, you gotta immerse yourself in the day-to-day lives of your fellow workers, both inside and outside the workplace. You want to be accepted as one of the crew, work hard and set an example as a team player. Don’t be looked at as an outsider with a ‘message’ to deliver – no one wants to be talked down to or lectured. Learn from others….

“Go to the bar after work and get to know people. Join the plant bowling league or the softball team, organize a party or picnic and invite your fellow workers; bring together whites, Blacks, Latinos, and women in a social setting where the barriers of racism don’t divide, but unite, even if only on a social level at first. An organizer has to gain the trust and respect of others and win their loyalty so when you go up against management, you’ve got a team on your side.”

One topic that comes up again and again is “white skin privilege.” Melrod explains, “When I worked in a tannery, I was the only white guy. I could have used my white skin to secure a better job that wasn’t as dirty or as physically punishing as the job as I was assigned. I didn’t do that. I wouldn’t allow the company to separate me from the other workers and them from me.” Rather, he always saw the fight against racial prejudice as central to the factory organizing he engaged in.

At one place where Melrod worked, the walls of the men’s bathroom were scrawled with racist graffiti. “All the workers, white and Black together, demanded that those walls be repainted and management jumped to it.” On other occasions, he was called “a Commie Jew.” After he won his first election as steward, someone spray painted, “Melrod wears a training bra.” “Now that was creative,” he recalls. “I wanted to meet that guy!”

Melrod has some criticism of himself as an organizer, including his opposition to involvement in electoral politics and his decision not to use the “levers of government” to the advantage of the union. For years, he didn’t vote. “I can see now,” he says, “that there are ways to use local politics and electoral battles for the benefit of the union and the working class.” What Melrod emphasizes again and again is to be where the workers actually are, not where one would like them to be. “The workers watched the TV show All in the Family, so I watched All in the Family,” he says. “I would initiate a conversation, for example, about Archie Bunker or his son-in-law Meathead who spent the entire show battling over racial prejudice and backward ideas. I’d use stuff from popular culture to get into political discussions. The conversation flowed naturally, not like I was delivering a political lecture.”

At American Motors someone dropped toxic cleaning fluid on his head from the fifth floor while he was handing out a flyer. “I went running to the room where the privileged guys hung out and demanded, ‘which one of you motherfuckers dropped that shit on my head?’” The lesson he took home from that incident was “You can’t be faint of heart. It’s a rough-and-tumble world…. I was always on the offensive and never backed down. I had to prove I had guts and let it be known I was no pushover. If you want respect as an organizer, stand your ground, even if you have to push yourself!”

Descriptions of factory work seem at times similar to the circles of Dante’s Inferno. There’s the Crucible Steel Casting Company, which “had earned its reputation as a tough, dirty, and dangerous place to work,” and there’s the Pressed Steel Tank Company where he feels “as if a thin layer of sand coated my eyeballs, and each blink irritated my eyes. Wheezing, I blew my nose, filling the rag with dark mucus-encrusted particles.”

Melrod also worked as a “tannery rat” and then as a “wage slave” at a “small plastic injection-mold factory” where he found himself “at the bottom of a large concrete vat, rushing frantically to clean the toxic residue of trichloroethylene (a cancer causing chemical) used to degrease the oil on metal paint trays.” He might as well have been back in nineteenth century Turin with Professor Sinigaglia.

Preceding union militancy, Melrod describes his early education, and his role in SDS at Madison, where he read Marx and Mao. As an undergraduate, he aligned with the local chapter’s Woody Guthrie Collective and became an adherent of the Revolutionary Youth Movement II (RYM II) faction, which contended with Weatherman. RYM II supported the Black Panther Party and embraced the ideology that the working class held the power to radically transform society with the long-term goal of ending capitalist exploitation.

Fighting Times ends with a dramatic courtroom trial in which Melrod was charged with libel and defamation. He and his co-defendants won. His opponents lost. The Kenosha News ran a front-page story about that victory that can serve as a summary of the memoir: “As a worker, he’s been fired for union activities. As a union activist he’s been branded a ‘commie’… Melrod’s role in Kenosha has almost always been to raise the dissenting voice.” Melrod himself is quoted as saying, “Dissent has to be the lifeblood of the union movement. Without it, it gets stale.”

If Melrod had a personal life during the time he worked in factories and built unions, he doesn’t say. That might not matter, either. After all, his political life was also his personal life; when you’re an organizer, you organize.

Over the last few decades, he has aged but he hasn’t gotten stale or mellow. He’s still feisty and combative. After life as an organizer, he became a lawyer and continued the struggle for justice in and out and around courtrooms, battling for the rights of defendants and their families who were messed over by cops and in some cases gunned down and killed by officers of the law. Jon Melrod has almost always known which side he’s on, going back all the way to his youth when he recognized the American version of apartheid and joined the battle to upend it and banish it from the land.

In some ways, Fighting Times was written for Melrod’s sons, who often wanted to know what he did back in the day. But it was also written for all the sons and daughters of Sixties radicals who became union organizers, and for the people of Kenosha, who have long protested against police brutality and who demonstrated against the “not guilty” verdict in the trial of Kyle Rittenhouse, who shot and killed two protesters and wounded a third in 2020. Fighting times are our times, much as they were in nineteenth century Turin, when organizers like Professor Sinigaglia showed up to lend their skills to the poor, the exploited and the outraged.

[Jonah Raskin is the author of For the Hell of It: The Life and Times of Abbie Hoffman, a professor emeritus at Sonoma State University and member of the California Faculty Association.]

To place a preorder for Fighting Times from PM Press or to read excerpts before the book is released.