An excerpt from a new novel about the radical Left in 1916 San Francisco

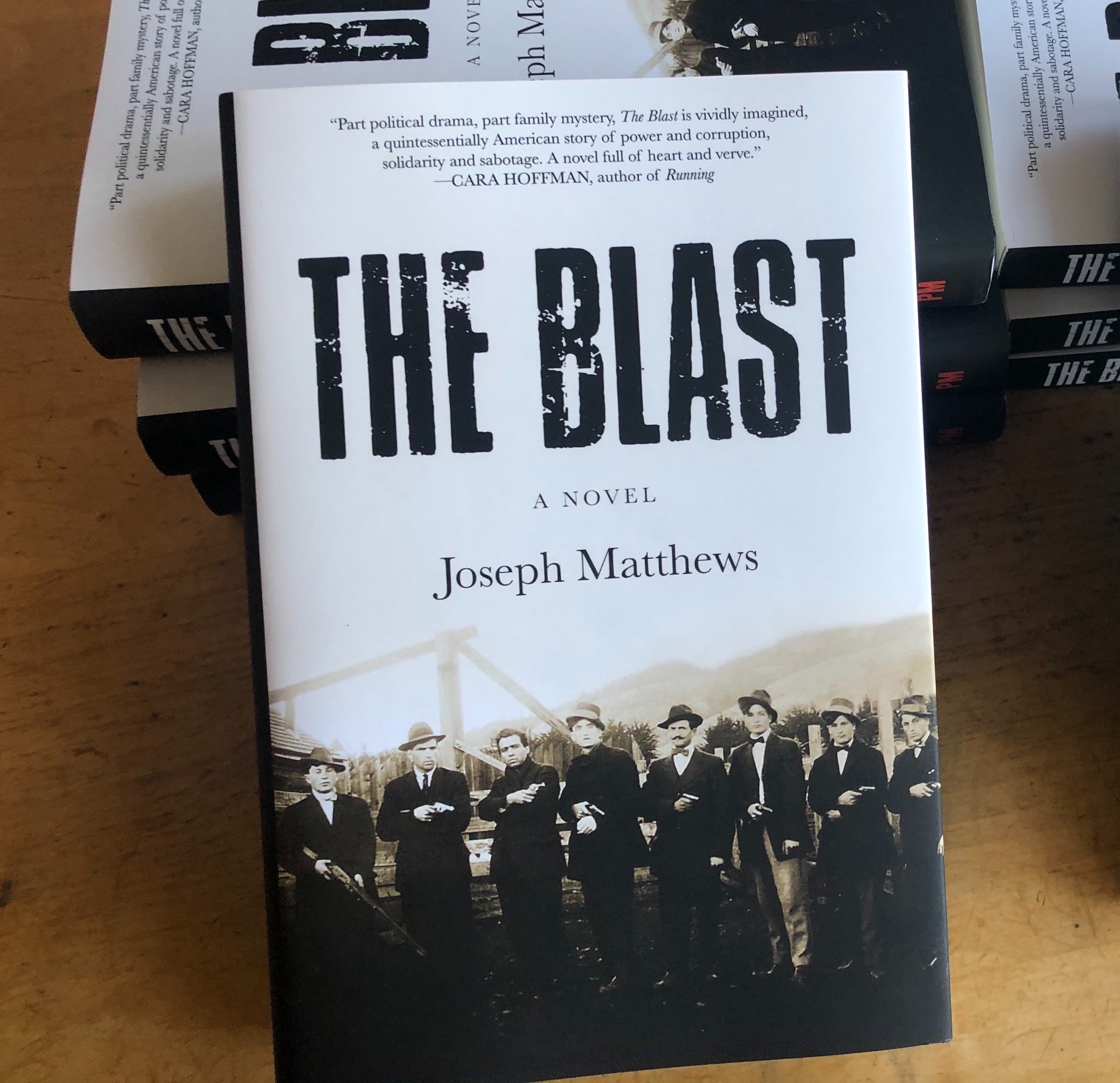

Excerpted from The Blast. Copyright © 2022 by Joseph Matthews. Published and reprinted by permission of PM Press.

When she’d arrived in San Francisco a few months before—alone, and with little more than her youth, a sketchbook, a general feistiness, and a few self-preservation skills she’d picked up on her travels—the first paid labor Meg found was in the all-female work brigade at one of the northern waterfront fish canneries. As with many other worksites in San Francisco that winter, the cannery had been embroiled in a labor fight, which Meg unwittingly walked smack into the middle of. The strikers’ complaints went beyond the usual: not just a recent cut in the already pitiful pay rate and a workday stretched to twelve hours but also a system whereby workers were laid off and called back in unpredictable spasms, depending on when the factory decided it wanted them, which meant that workers had to show up at the cannery every day before dawn even though they might go for weeks without getting “hired” on, and if hired might be laid off again, with no notice, a day or two later. Moreover, the work was cold, wet, filthy and dangerous, with no help for the many women made sick or injured. On top of that, and most galling of all, was widespread abuse by the foremen, not itself unusual in a nonunion factory but which in this place took particularly egregious forms because all the workers were women: a constant spew of lewd remarks, frequent gropings, and demands for sexual favors in exchange for better work assignments or, given the at-will hiring system, for any work at all.

Adding to the cannery women’s travails was their invisibility to—the willful blindness of—the city’s traditional labor unions. The women had no specific skills, the labor leaders would say when pressed, and did not fit any particular craft or trade union, so their requests to the central labor council for some sort of recognition and, thereby, support in their fight against the cannery owners were ignored. They were not truly workers, the mainstream unions said; they were just women who sometimes took on work.

So the women at this particular cannery picked up the cudgel on their own and, to everyone’s surprise—including most of the women themselves—went out on strike shortly after Meg began working there. Meg herself knew nothing of unions, factory wars, strikes and lockouts, or much else in the world of paid labor. But the righteousness of the women’s cause was obvious to her after only a few weeks of spotty work in the cannery, during which she was repeatedly set upon by two lecherous foremen at the same time she found that her pittance of pay barely covered the rent for a shared closet alcove, referred to unblinkingly by the landlord as a room, and the cost of sporadic minimal meals. And she had only herself to worry about, unlike many of the other women there who had children to house, clothe and feed. Meg was also mightily impressed by the women’s energy and spirit of resistance, despite exhaustion from their labors, as embodied by one woman’s speech, consisting of no more than three extremely well-formed sentences, hollered from atop a wooden packing crate to the assembled workers outside the cannery the night the strike was called. “No. . . more. . . fucking. . . with us!” the woman—wiry, wild-haired, thirtyish, wearing flappy trousers and a denim work jacket—bellowed the double entendre toward the lighted windows of the factory management’s upper story offices, then turned back to the cannery women: “Now. . . they can go… fuck. . . themselves!” The women cheered wildly. But the speaker wasn’t quite finished. She turned and pointed to a representative of the labor council, lingering at the back of the crowd, who had showed up earlier to tell them they had no official sanction for a strike: “And you, you suck-ass shit-for-a-heart, FUCK. .. YOU… TOO!”

That was it, all the organizing the women needed: they were out on the picket line the following morning. And it was all the convincing—in language both startling and exhilarating to her—that Meg needed to join them.

It turned out that the vernacularly proficient orator was a former cannery worker named Rebecca—she called herself Reb—who was now allied with the local branch of the Wobblies, the Industrial Workers of the World. In recent years these San Francisco Wobblies had formed what they called a “mixed” union local, which included many categories of workers shunned by the city’s traditional trade unions: Latins, a term of disdain and exclusion when used by employers and mainstream unions but embraced proudly by the members of this Wobbly local, which included people of Italian, Spanish, Basque, French and Mexican heritage, immigrants and US-born alike, many of them highly skilled but forced by employer and union ethnic line-drawing to do only low-paid unskilled labor; Blacks, many of whose families had been in the city since shortly after the Civil War but who had never been allowed into most of the traditional trade unions; and Asians, including a few Japanese Americans and Filipino Americans and a handful of second- and third-generation ethnic Chinese young men who had braved the hostile reception of the outside world, not to mention their own families’ disapprobation, by consorting with people beyond the city’s tightly hemmed Chinatown.

The Wobblies opposed the self-segregation of organized labor into individual craft unions—carpenters, metalworkers, seamen, longshoremen, etc.—through which, the Wobblies believed, labor was too often divided against itself. On the other hand, Wobblies were always ready to lend their bodies to any of these unions or to any other workers who were actively engaged in battles with their employers. So the first morning of the women’s cannery strike the Wobblies sent a dozen members, from the mixed local’s headquarters in nearby North Beach, down to the waterfront to join the women on the picket line. They meant to offer corporal support to the women, particularly if, as often happened, private enforcers hired by the factory owners got nastily physical with the strikers when bringing in scab replacement workers. But the cannery women, while glad for the Wobblies’ appearance, decided to handle any confrontation themselves, consigning the Wobbly men to holding picket signs and yelling encouragement from the sidelines.

Local police ranks were filled with working-class lads, many of whose families had deep union roots in this heavily union town. So in general street cops tended not to intervene in labor confrontations unless and until things turned particularly violent or destructive. Which this one soon did. Bloody fights broke out between the striking women and the private security thugs who tried to bludgeon a path for the scabs to pass through the picket lines. And after one of the scab women got thrown off a wharf into the bay, the police finally stepped in to break it up. When it was all over for the day, the cops hadn’t arrested any of the scabs or security men, but neither had they arrested any of the women strikers. The only person they’d hauled off—at the insistence of their supervising captain—was one of the cheerleading Wobblies, charging him with inciting a riot: despite sympathy for traditional unions among the cops’ rank and file, the police brass had serious antipathy toward the more radical Wobblies; moreover, in the case of this particular strike by the cannery women, the police captain on site simply couldn’t get it into his head that there’d been no male behind it all.

A number of strikers had been badly beaten up in the melee, and Meg found herself tending to the wounded. This was not a fully conscious decision, and certainly not from a sense of vocation, which she had decidedly rejected the year before by walking away, right on the verge of taking a diploma, from her two years of nursing school. But she felt lost in the confusion following the picket line battle, and binding wounds was at least some way she knew how to be helpful. Reb, the fiery orator from the night before, had also been a fiery fighter against the scabs and security men that morning, and she came out of the scrum with a heavily bleeding scalp. Meg was able to stanch the blood for her, clean the wound with a bit of bay water she confidently directed someone to fetch, and with a scarf created a makeshift bandage which kept enough pressure on the wound that Reb was able to walk, gingerly, without bleeding too much more. Reb, who’d become a nurse after her stint in the canneries, liked this girl’s assertiveness and resourcefulness, particularly appreciating the efficacy of the jaunty headband. So when her first few steps were tottering, she accepted Meg’s proffered arm, as well as her contention that Reb should have her injuries properly treated. Another woman managed to hail a taxi, and Meg and Reb climbed in.

Reb directed the taxi into nearby North Beach where it stopped in front of a multilevel dark wood modernist building with a small sign that said Telegraph Hill Neighborhood House. Meg helped Reb struggle up some stairs into a lovely shaded inner courtyard, then up another flight and into a large sunlit room with high windows, a handwritten paper by its open door saying simply “Dispensary.” There, two older women were tending to a couple of children in what was some sort of makeshift medical clinic: an examining table, a small cot, four simple wooden chairs along one wall, two cabinets with a thin array of medical supplies and medicines, a chicken wire cool box with some fruit and bread, and a sink. The dispensary women moved quickly when Reb, whom Meg had thus far managed to keep upright, buckled to the floor. They nudged Reb onto the table, told the children to return later, and began to treat her wounds.

Click here to read an interview about The Blast between Joseph Matthews and Evangeline Riddiford Graham.

Jospeph Matthews is the author of fiction and nonfiction books including the novels Everyone Has Their Reasons (PM Press, 2015) and The Blast (PM Press, 2021).