By Jeff Stilley

H-Net

September 2021

Native-born working-class Black radicalism in the United States during the 1910s-20s is a challenging object of historical investigation. One approach to this topic is through Harlem, New York, a hotbed of Caribbean-influenced radicalism. Biographies of A. Philip Randolph, for example, provide a window into early experiments there with reading groups, unions, and revolutionary politics. Few industrial cities in the United States had significant numbers of African American workers prior to the First World War, but Philadelphia, Chicago, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Kansas City, Indianapolis, and Cincinnati have hosted sizable Black populations since at least the turn of the twentieth century. How did politically engaged Black workers outside of Harlem interpret white supremacy, imperialism, capitalism, and the relations between them? How did they organize among themselves, and how did they relate to trade unions, industrial unions, white revolutionaries, and professional African Americans?

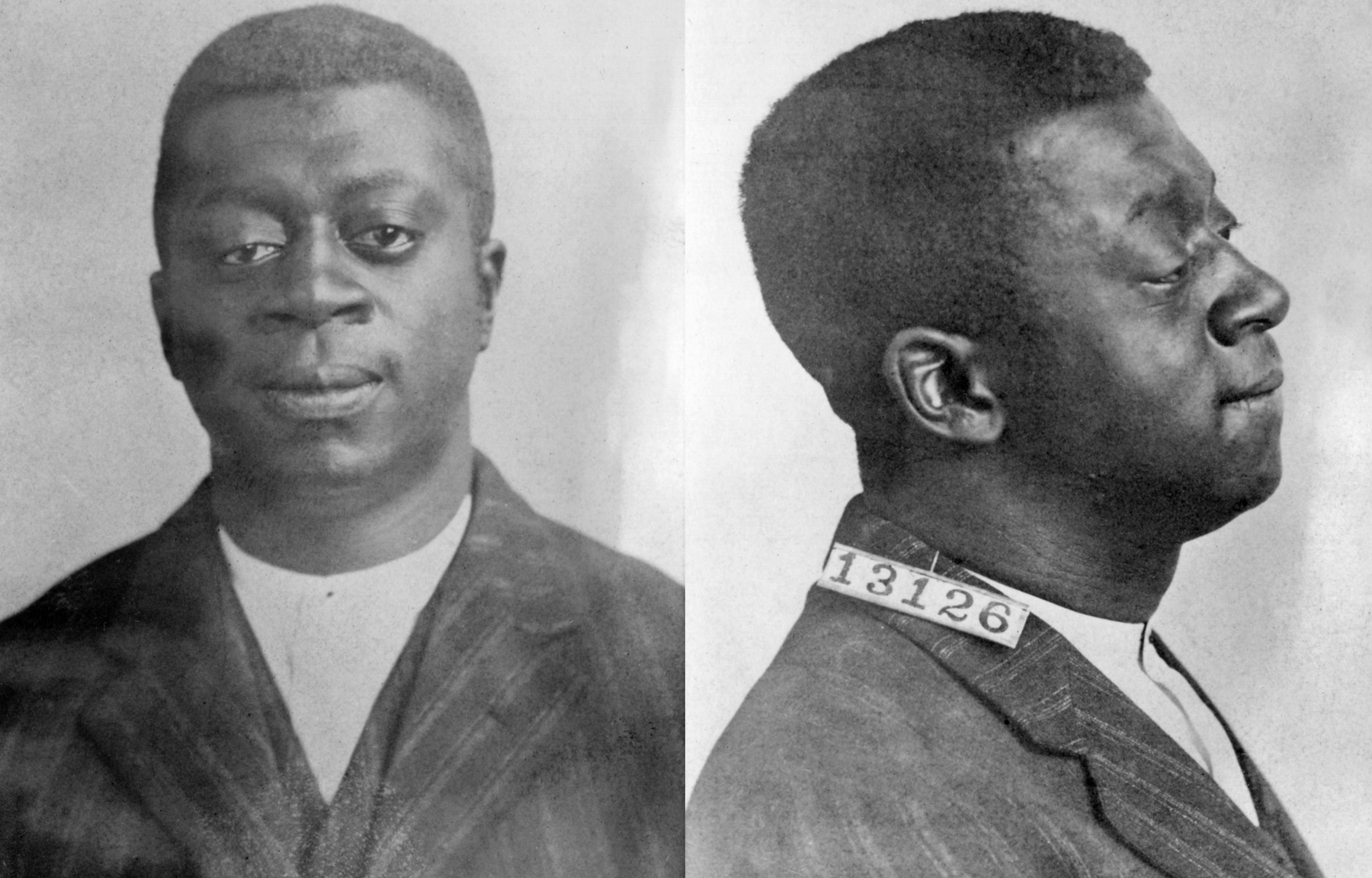

Peter Cole’s indispensable biographical essay on Ben Fletcher provides fascinating insights into these questions for Black longshore workers in Philadelphia. The essay is followed up with nearly 100 primary-source documents, allowing readers to fully understand Fletcher’s life. Born in Philadelphia in 1890, Fletcher helped lead the powerful Industrial Workers of the World’s Local 8 of the Marine Transport Workers during the 1910s and beyond. About one third of the members were Black, making it one of the most successful attempts by the IWW to attract African American members. While much is not known about Fletcher’s early life, Cole deftly fills the reader in on what life must have been like for working-class African Americans in Philadelphia at that time. Between 1913 and 1918, Fletcher won the loyalty of racially and ethnically diverse dock workers towards Local 8 through direct action, which resulted in worker control of hiring practices and working conditions. Following the United States’ entry into the First World War, the government jailed dozens of IWW organizers, including Fletcher. After years in federal prison, Fletcher returned to Philadelphia, only to have to fight pro-communist Wobblies within the organization. He led some members out of the IWW in 1923, after American Federation of Labor competition and an employer lockout undermined Local 8’s workplace control. Until he suffered a life-altering stroke in 1933, Fletcher remained at the forefront of revolutionary syndicalism, delivering rousing speeches across the country. He lived the last years of his life in New York City, dying in 1949.

Fletcher used his unmatched speaking and organizing skills to become one of the most well-known labour agitators of the era. Yet, as Robin D.G. Kelley’s foreword highlights, his memory has been erased in left history of the era, including by the ahistorical whiteness of the labour movement in the film Reds. Thus, Cole fills in a huge gap in US history by piecing together everything known about Fletcher’s politics, which had considerable influence across left movements. Fletcher’s analysis of class and race are of particular note. For example, in a letter he wrote from prison in 1920, he argued that a revolutionary workers’ movement could only be interracial in nature, because capitalists would rely on Black workers alienated by the trade union movement to disrupt revolutionary momentum.

Fletcher outlined his program for an interracial and revolutionary syndicalist labour movement in a 1923 essay. He wrote that labour organizers should actively help Black workers entre skill categories normally filled by white workers, vigorously fight for civil rights in the South, and hire Black organizers to agitate among African American workers. His basic orientation was “unite and fight,” with the recognition that institutional racism in skilled labour markets, the lack of political rights under Jim Crow white supremacy, and everyday social divisions produced major barriers to universal class organizing, all of which had to be addressed to build trust and commitment among Black workers.

What new insights does the book provide historians about Ben Fletcher and Local 8? Howard Kimeldorf featured Fletcher in Battling for American Labor(University of California Press, 1999), which argued that American workers of the period acted with a pragmatic syndicalist impulse, rather than through ideological motivations. Although Kimeldorf credited Fletcher for being the driving force behind Local 8’s interracial unionism, Kimeldorf also asserted that rank-and-file longshoremen just wanted control and security over their jobs, and did not care about the politics of the IWW, an argument reflecting Fletcher’s perspective on rank and file members. This revised and expanded edition of Ben Fletcher, however, undermines such a narrow view. Two articles from Philip Randolph’s Messengerillustrate that, by 1921, Local 8 held weekly political forums that attracted hundreds of white and Black members looking to democratize knowledge and educate themselves on issues of racism and capitalism. The work Cole did to curate this book makes it clear that Philadelphia longshoremen’s successes with interracial industrial unionism was not merely the outgrowth of the production process or even Fletcher’s singular influence, but also the result of a political culture within Local 8. Even if these workers were not particularly interested in all of the theories and ideology of the IWW, they certainly cared deeply about the politics of the day, and how they affected organizing dynamics within the union.

Cole’s book is an indispensable secondary and primary source for any historian interested in the dynamics of race in working-class formation in the United States prior to the development of the Congress of Industrial Organizations, particularly in a non-Communist-party context. The inclusion of several IWW cartoons, posters, and pamphlets aimed at Black workers is a bonus for left historians. The book may also hold important insights for scholars trying to get a handle on Black working-class politics in the handful of industrial cities that had significant numbers of African American workers prior to the First World War.

Peter Cole is a professor of history at Western Illinois University in Macomb and a research associate in the Society, Work and Development Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. Cole is the author of the award-winning Dockworker Power: Race and Activism in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area and Wobblies on the Waterfront: Interracial Unionism in Progressive-Era Philadelphia. He coedited Wobblies of the World: A Global History of the IWW. He is the founder and codirector of the Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project.