By Sean Gerrity

Smallaxe.net

February 2021

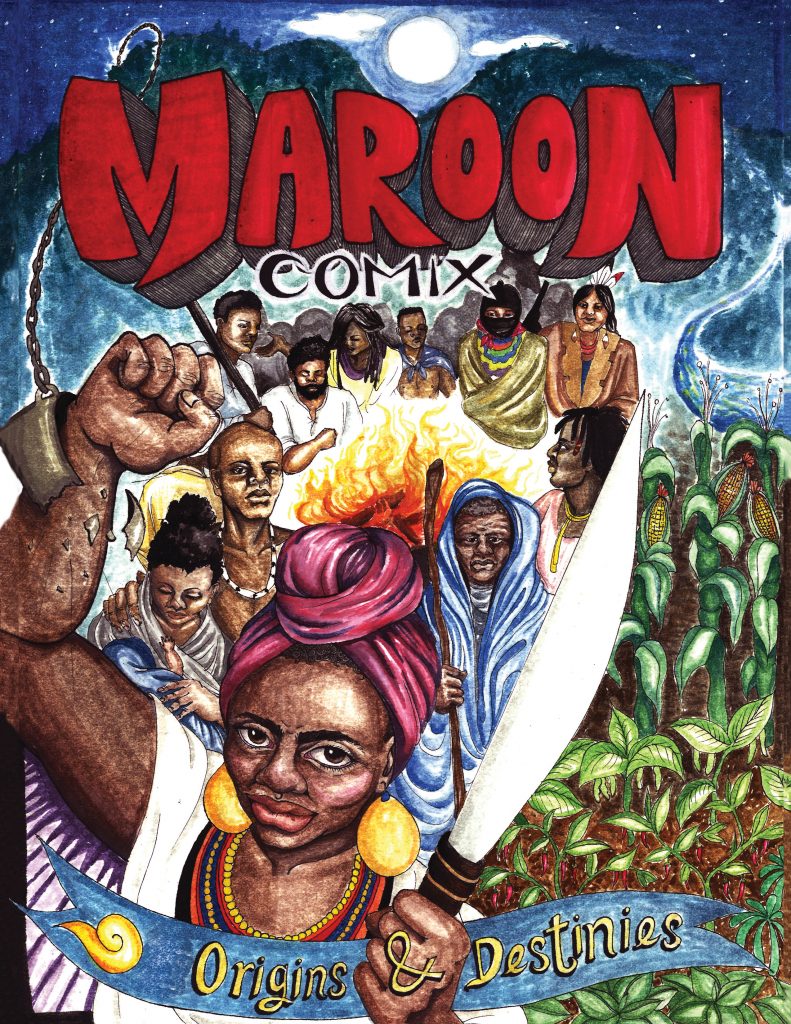

Maroon Comix defies pithy description. It is as multifaceted in form, content, and presentation as were the Maroons and types of marronage it elucidates. On the title page, the book describes itself as “conceived, compiled, and coordinated” by Quincy Saul; names the six illustrators; and lists a rich variety of scholars, activists, and artists who are cited throughout. Maroon Comix concludes with the “Maroon Library,” a robust bibliography of published work, much of it scholarship, related to all aspects of Maroons and marronage.

Maroon Comix is at once history, biography, and manifesto, but it engages with these familiar modes even as it disrupts and transcends them. It is broken into seven chapters with distinct styles of illustration and methods of representation. The first chapter, “Initiation,” does indeed serve to initiate the reader into the world of the Maroons through “a journey off the map,” evoking “the histories and prophecies of the maroons, who for centuries built societies and networks of liberation around the world” (1). The chapter contains quotations from scholars such as Mavis Campbell and Richard Price as well as from imprisoned political activist and author Russell Maroon Shoatz. It is set against a backdrop of colonial violence, African resistance, and the flight from slavery characterized by the Maroons who “broke their shackles; took to the woods or swamps or mountains; found, took, or grew their own provisions while simultaneously fighting and defeating the former slave masters” (2; quoting Shoatz).1Maroon Comix quickly establishes that marronage—while taking on distinct resistant forms against the backdrops of distinct forms of slavery and colonialism throughout the western hemisphere—was (and is) a liberatory practice common to enslaved black populations across space and time.

The second chapter, “Slavery and Liberation,” offers what it calls “The Story of Slavery” and “The Story of Liberation,” which weave a sophisticated narrative linking the histories of imperialism, colonialism, slavery, capitalism, racism, resistance, revolution, and struggles for freedom. “The story of liberation begins in the first second of slavery,” we are told, which is a story of those people, Maroons, who were “hunted . . . out of history” in places ranging from the United States to Haiti, Jamaica, Suriname, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and beyond (7, 8). This chapter makes it clear that the story of the Maroons is not simply one of resistance to and escape from chattel slavery; rather, it is the story of a people who “built liberated societies, whose spirits survive to this day” (13). The illustrations depict struggle as well as triumph, revealing a diasporic tradition of freedom-seeking that not only characterizes the past but may inform the present and future.

Chapter 3, “I Am Maroon,” departs significantly from the previous two chapters. It consists of surreal, stylized visuals of heroes of black liberation from all over the hemisphere, accompanied by short biographical sketches of each. The drawings are constituted by long, swirling lines that weave the depictions of the Maroon figures into the fabric of their physical landscapes, blending person with place and suggesting the Maroons’ potential for transforming spaces of enslavement to spaces of freedom and autonomy. The chapter includes sketches of Maroon figures from the Caribbean, Latin America, Brazil, and the United States, including Granny Nanny of the Jamaican Maroons, Dutty Boukman of Haitian Revolution fame, and Ganga Zumba, king of Palmares in Brazil. Of particular interest is the fact that Harriet Tubman is included among the roster, along with the Black Liberation Army of the Vietnam era in the United States. Without explicitly doing so through narrative, this chapter evokes an interconnectedness of freedom-seeking experiences untethered from narrow conceptions of what a Maroon was or could be.

“The Dragon or the Hydra?,” chapter 4, depicts the forces of colonial oppression in the Caribbean as dragons and the Maroon communities who fought against them as hydras, arguing that “Because they came from many different backgrounds, they [Maroons] had to have a decentralized and democratic form of organizing” (39). It builds to a depiction and story of the Haitian Revolution as a model of successful organization of forces necessary to repel imperial subjugation of black populations. The spirit of the Haitian Revolution then informs the book’s final main chapter, “Modern Maroons,” which suggests that the spirit of marronage may be weaponized in the present day to ward off the tyranny brought on by the consolidation of global racial capitalism. “Maroon Comix are stories insurgent against singular History, armed with art. Not a chronology but a collage; a pattern and a program that reflects maroon realities,” Saul explains in the book’s concluding “vision quest/manifesto” (58).

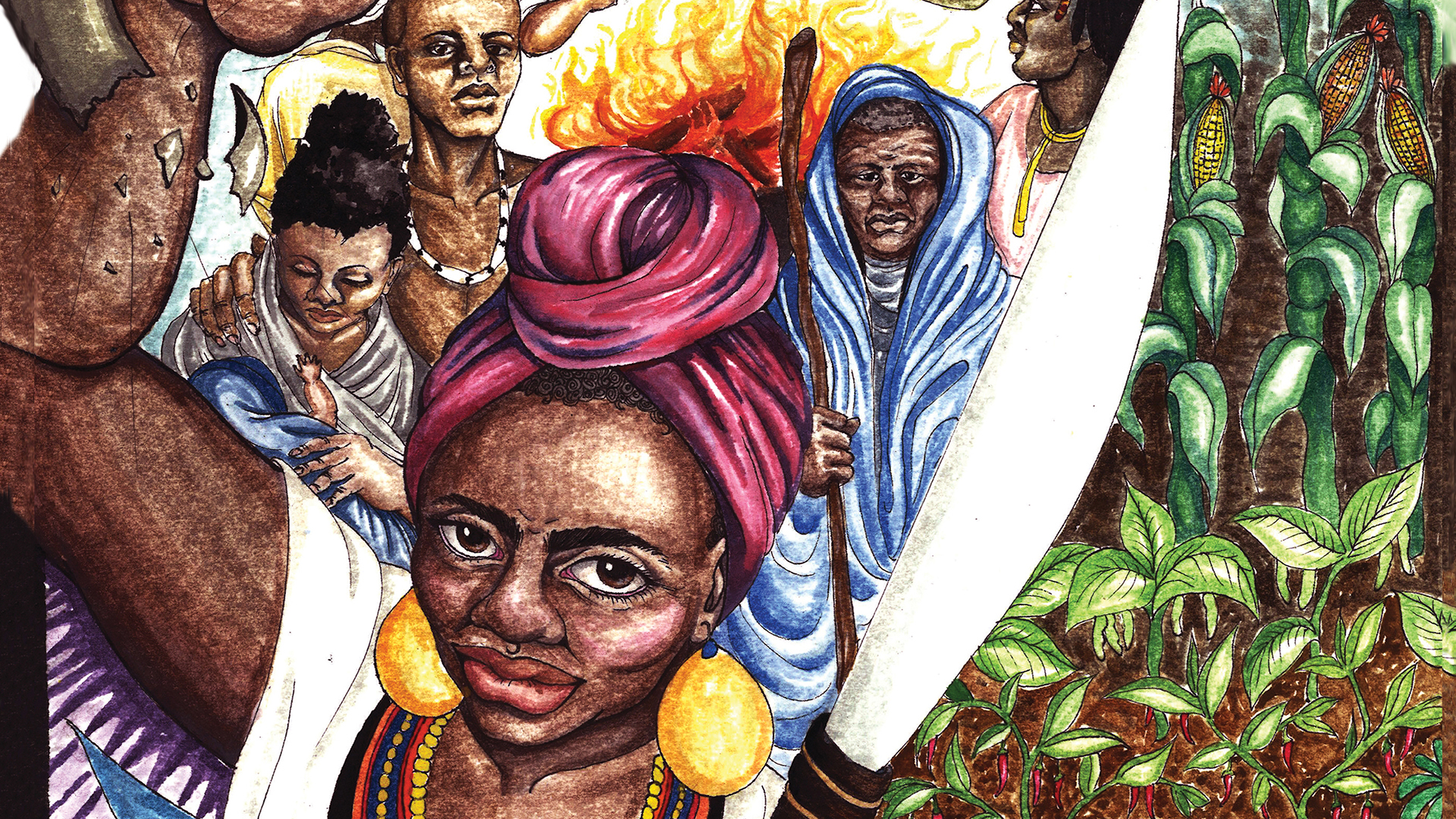

Because six illustrators worked on Maroon Comix, its visual style is rich and variegated. While the book’s cover is in color, the rest is drawn in black and white in styles that change from chapter to chapter. It would be impossible to do justice to the aesthetics of the book through description; it must be experienced to take in its full effect. What unites the diverse artistic styles is the desire to bring the hidden and obscured lives of Maroons into dramatic and fully realized view for readers. The visuality of the book promotes accessibility while also realizing the depth and variety of Maroon experiences through text and through elaborate images that incorporate elements of the real, surreal, symbolic, and imagined. The book’s visuals complement its thematic interest in imagining liberatory futures that do not depend upon previously conceived dominant paradigms.

One of the most profound achievements of Maroon Comix is its appeal to a wide-ranging audience. It is appropriate for and compelling to scholars as much as to a general audience, to those with scholarly knowledge of marronage as much as to those with only a passing familiarity with the history of slavery. The final chapter ties the legacies of marronage and resistance to slavery to present-day global struggles for autonomy, independence, and civil rights. The scope of its call to arms is decidedly international and coalitional. What is needed, the book suggests, is a fundamental rethinking of the past if we are to be capable of envisioning a just future, and marronage is the lens through which all of this becomes possible.

Sean Gerrity is assistant professor of English at Hostos Community College of the City University of New York. His research focuses on the ways that representations of marronage in US antislavery literature disrupt conventional geography-based notions of freedom and unfreedom, revealing alternative freedoms characterized by black community and world-making. He is currently at work on his first book, “A Canada in the South: Maroons in American Literature.”

[1] Russell Maroon Shoatz, Maroon the Implacable: The Collected Writings of Russell Maroon Shoatz, ed. Fred Ho and Quincy Saul (Oakland, CA: PM, 2013), 34.