Industrial Worker

May 9th, 2021

In anticipation of his upcoming book talk, historian Peter Cole discusses the life and times of the IWW’s most prominent Black leader.

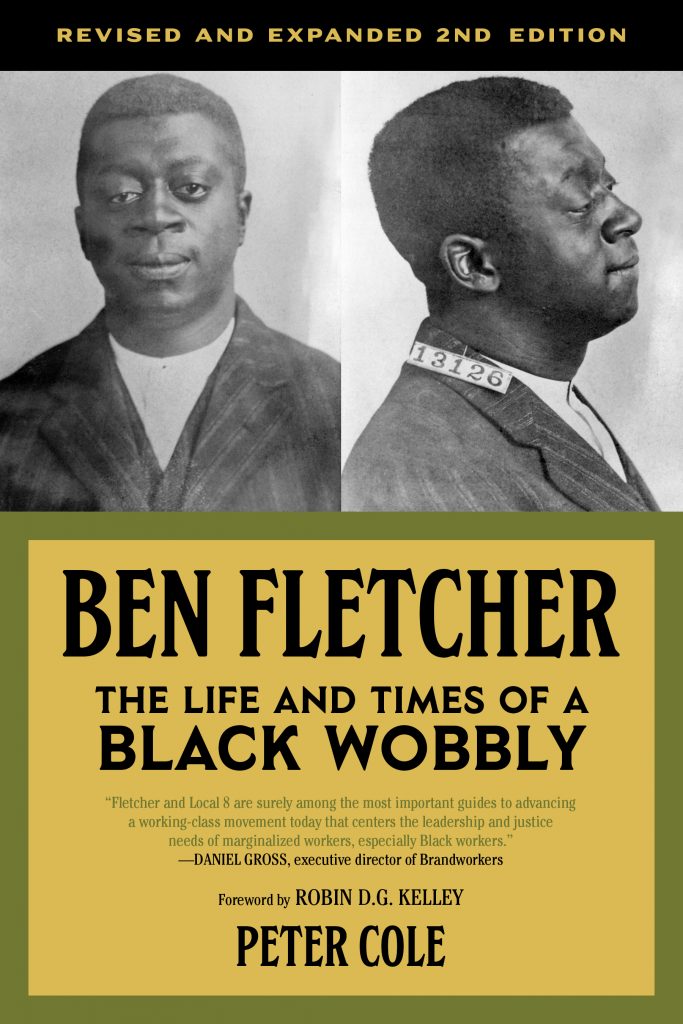

On Saturday, May 15 at 3 PM Eastern, the Industrial Workers of the World’s Communications Department will be hosting an online book talk with historian Peter Cole about his recently reissued biography, Ben Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly. In anticipation of the event, Industrial Worker caught up with Cole to learn more about Fletcher, his role in the IWW, and what we might take away from that history today. The conversation below has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

Industrial Worker: Who was Ben Fletcher?

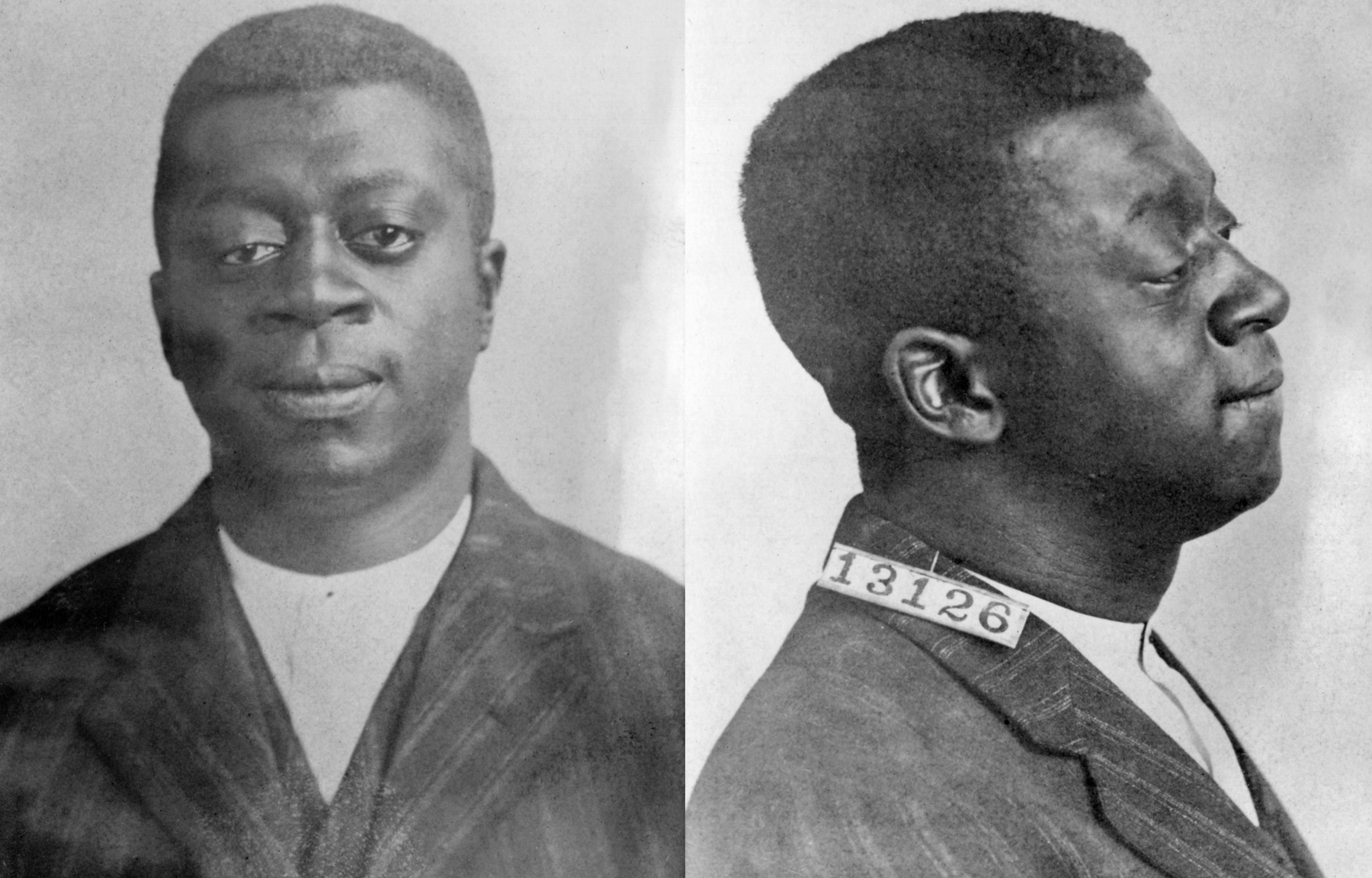

Peter Cole: Ben Fletcher was an African American born in Philadelphia in 1890. Around 1910, he became a member of the IWW, then in the 1910s, became a leader in the IWW in Philadelphia, where he helped lead a union of dockworkers, called “Local 8.” The approximately 4,000 men were a third African American, a third Irish and Irish American, and a third East European immigrants — so an incredibly diverse waterfront workforce. He also then became widely known across the US as the most prominent African American in the entire IWW, ever.

As a result of his leadership, but also his prominence, Fletcher was one of the IWW leaders arrested in 1917 and put on trial in 1918 for federal charges of espionage and sedition. As a result, Fletcher then went to prison in Leavenworth, Kansas, with many other Wobbly leaders. When he got out in the early 1920s, Local 8 had been weakened due to governmental and employer counter-offensives. Fletcher remained committed to the IWW through the rest of his life. He died in 1949.

Fletcher was the most important African American in the IWW, and that’s because the union that he came to lead was the best example of interracialism in practice. You could argue that Local 8 was the single most effective integrated institution, not just union, in its era. Fifty-one years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Local 8 had voluntarily integrated itself and forced the employers to accept that change — employers who had created a segregated workplace.

How were Fletcher and Local 8 unique in the US labor movement of the time?

In a country that was deeply prejudice against Black people and immigrants, Local 8 was entirely against the grain. A Black-led, multi-racial, multi-ethnic union simply did not exist.

When the IWW was founded, it was founded very intentionally as a challenger to the American Federation of Labor, which in the early 20th century was very openly exclusionary. The AFL didn’t organize many African Americans, and when it did, it was often into segregated locals. Local 8 was generations ahead of other unions when it came to organizing Black people, treating them equally, having Black leaders, having zero discrimination on the job. They integrated their “gangs” [teams of dockworkers], they integrated their leadership, they integrated their events against the grain.

What should organizers and activists today take away from Fletcher’s experience?

In the words of Howard Zinn, I very much believe in the idea of a usable past, the idea that we can learn from the past and actually look at examples of practices, actions, politics that are worthy of replication. We are obviously, as a country and world, not over prejudice against Black people, immigrants, and others.

Another lesson echoes the words of the legendary Wobbly folk singer Utah Phillips: When we are taught our history, we are actually taught the history of the ruling class, not of the working class. We need to know this history. Who we are is who we were.

Naturally, I am biased. I deeply believe in this history of Ben Fletcher and the union that he was a part of — but I don’t think I’m alone in imagining this history is meaningful. If it has been done, it can be done again.