By JJ Amaworo Wilson

In his introduction, Jesse McCarthy writes that the twenty essays in Who Will Pay Reparations on My Soul? are true to the word’s French etymology: essai. Essais are “attempts.” But in this outstanding collection, the pieces are more than this. They are experiments that audaciously integrate art, music, literature and politics, all seen through the lens of race.

McCarthy’s range is facilitated by his background. When he was eight years old, his journalist parents whisked him off to France. He immersed himself in the culture. Although he belonged to the middle classes by dint of his parents’ work, his color and his instincts led him to the rougher banlieues, the French equivalent of the projects, where Paris’s youthful, rebellious energy is fueled by its music, graffiti, street fashion, and slang. McCarthy’s cultural references are thus cross-continental, cross-caste, and multilingual as well as interdisciplinary.

Who Will Pay … begins with a bang. The portrait staring from the book’s cover is of Juan de Pareja, the slave who belonged to the great 17th century Spanish painter Diego Velázquez. Sitting for the painting that would make his master famous, de Pareja gazes at us calmly, his look belying his status as Black chattel. McCarthy not only rescues de Pareja from near-obscurity, but makes a case for him as an artist. Indeed, it was de Pareja’s painting ability, developed in secret with his master’s tools, that led to his freedom. The only surprise is that McCarthy misses the fact that pareja means “partner” in Spanish, an apt name with the fates of master and slave forever yoked together by this portrait.

“The Master’s Tools” is a dazzling opening gambit, a setting out of McCarthy’s stall. He references Beyoncé, Du Bois, Jay Z and Foucault – going high and low and straddling the altitudes with ease. Other standout essays include “The Origin of Others,” which is an examination of the work of Toni Morrison; “Language and the Black Intellectual Tradition”; and “An Open Letter to D’Angelo” that is likely to send you straight back to D’Angelo’s 2014 album “Black Messiah.” The only piece that feels dated is “Underground Man,” simply because it was obviously written before Colson Whitehead’s novel The Underground Railroad, which it critiques, scooped up all the big prizes including the Pulitzer and the National Book Award.

While McCarthy is a polymath and a superb writer, occasionally you wonder what he’s up to. At one point, in the essay “Black Dada Nihilismus,” his prose goes haywire and you think he’s lost it. But then you realize he’s mimicking Black Dada, riffing like Basquiat and Baraka, throwing together conceits, neologisms, and found images.

Elsewhere, he produces epiphanies like candies from a slot machine. He points out that Black resistance has “from the very beginning channeled itself through cultural and aesthetic forms and practices.” He writes, “Black life in this country has always been predicated on and inextricably bound up with negligence, casual violence, and dishonorable death.” He explains how Black rappers invariably state precisely where they’re from, but “[a]ll these blocks, all these hoods … are effectively the same: they are the hood, the gutter, the mud, the trap, the slaughterhouse, the underbucket.” Even as we nod in recognition, we realize that no one has ever put it exactly like that.

For its penetrating thought, its joyful language, and its eclectic wanderings among the peaks and valleys of high and low culture, this book is an act of sublime generosity from a brilliant mind. Essai? Triomphe.

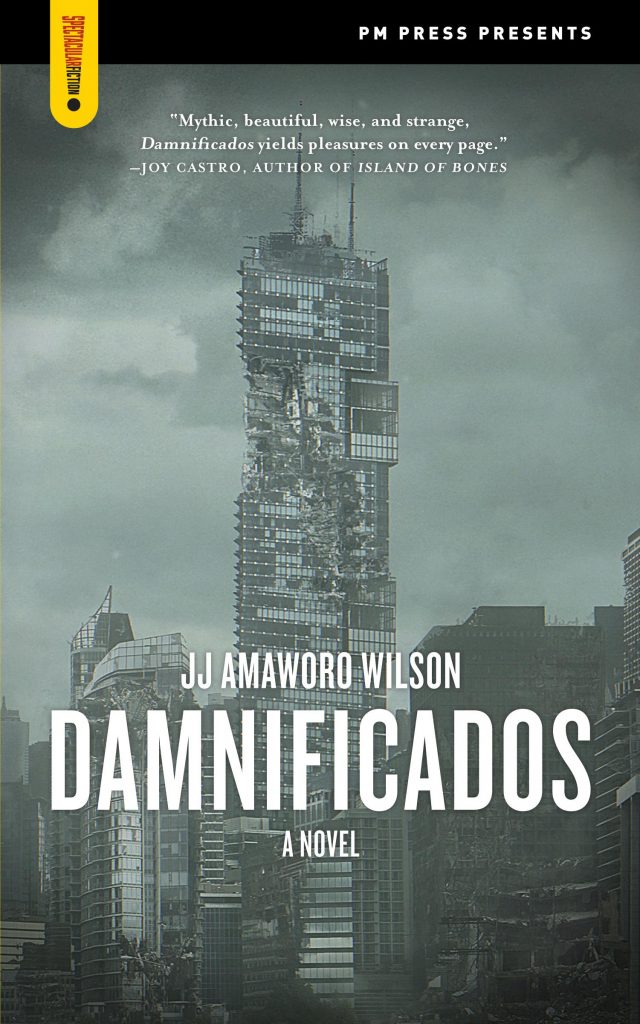

JJ Amaworo Wilson is a German-born, British-educated debut novelist. Based in the U.S., he has lived in 9 countries and visited 60. He is a prizewinning author of over 20 books about language and language learning. Damnificados is his first major fiction work. His short fiction has been published by Penguin, Johns Hopkins University Press, and myriad literary magazines in England and the U.S.