By Joe Allen

Tempest Magazine

December 10th 2020

Our efforts were worthwhile” – D.R.

David Ranney was one of tens of thousands of radicals across the U.S. who shifted their political activism from campuses and communities into industrial workplaces during the 1970s. His experiences—and the political lessons he drew—are recounted in his book Living and Dying on the Factory Floor: From the Outside In and the Inside Out. His memoir is one of the most refreshing and interesting accounts of that era.

Today, a new generation of socialists are once again discussing labor strategy, with some looking to the various “industrialization” strategies that the Left pursued in the 1970s. Ranney’s reflections show both the potential and dilemmas of highly educated radicals organizing in an industrial setting, and straightforwardly deals with the issue of racism and national oppression in the working class. Whatever side you fall on that debate, Ranney’s book should be at the center of the discussion on its merits.

A long time professor of Urban Planning and Public Affairs at the University of Illinois (UIC), Ranney was spurred to recount his experiences in industrial workplaces in Southeast Chicago and Northwest Indiana. “My irritation at politicians and some economists who advocate ‘bringing back middle class jobs to make America great again’ caused me to reflect on my own time on the factory floor some forty years ago,“ Ranney wrote,

“My experience doing factory work in the 1970s and 1980s and my subsequent research suggest that these jobs were not really ‘middle-class’ and they were hardly ‘great’.” While many of these jobs provided a living wage, at least through the 1970s, his recollections of factory life were not romantic. Factory work was, “brutal, unhealthy, dangerous, and caused serious environmental degradation. One former steelworker said to me that many factory and steel mill workers hated their jobs during this period. This observation was consistent with my own experience.”

The daily toil was also monotonous, and of course, many of his co-workers turned to self-medicating. A particularly noxious favorite was a concoction called “shake n’ bake,” made of cheap wine and lemon juice powder; an often futile and sickening approach to coping with the boredom, daily stupidities, and indignities of these jobs.

SDS Crack-Up

Ranney left a position as a tenured professor—a “comfortable perch,” he called it—at the University of Iowa, in 1973:

I was highly involved in local political and social activities…including opposition to the Vietnam War, supporting the demands of various civil right groups, critiquing the political outlook of textbooks used in major survey courses at the University , and experimenting with new social forms by organizing daycare, food and housing co-ops.

Yet, Ranney felt restless. “I increasingly began to feel that we were operating in a bubble that really didn’t exist beyond Iowa City.” So, he headed off to Chicago and joined his friend Kingsley, who’d opened up a storefront pro bono legal clinic called the Workers’ Rights Center on the Southeast side of Chicago. Here was the day-to-day nitty-gritty work that Ranney craved.

“It was a time of great optimism and hope,” Ranney recalled. It was also a time for making political choices. Ranney first joined the New American Movement (NAM), then the Sojourner Truth Organization (STO). These were two of many Marxist organizations, as he described it, that were “spin-offs of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS),” the largest campus-based radical student groups of the 1960s.

[T]hey all shared the belief that a worldwide revolutionary movement would result in some form of socialism. But we were deeply divided over how that would happen and what socialism would look like,” Ranney wrote. “Many sent members to work in factories. The organizations I belonged to were different.

Like another contemporary, heterodox Marxist group, the International Socialists, the STO was different because they didn’t believe that the USSR, China, North Korea, Cuba, or Albania were socialist. They also shared the belief that socialist society could only be created by “mass organizations at the workplace.” The STO also prioritized the struggle against racism inside the working class. Influenced by the ideas of Ted Allen and Noel Ignatiev, STO believed that too often radical activists side-stepped the issue of racism for an elusive “unity” that actually prevented it.

Working at the Workers’ Rights Center started to be untenable for Ranney. Money was tight, and he decided, with the support of Kingsley and his partner Beth, to look for a job at a nearby factory. “Many left groups [were] sending members into factories to organize workers. This is not the case with me,” Ranney wrote. “But part of my decision involves a bit of bravado on my part and a romanticism of factory work itself.”

Motivated to write his memoir to debunk the enduring myth of “good jobs,” Ranney’s reflections tell a much bigger story.

Chicago Shortening

“Industrialization” was an awkward sounding term that mostly involved left groups sending middle-class student activists—whose primary political experience was campus based— into long term jobs in key industries, in the hope of radicalizing workers.

The goal was to transform the class nature of the post-SDS left, or the largely Stalinist New Communist Movement. The rank and file rebellion of the 1960s and 1970s—best documented by veteran socialist Stan Weir—provided a road map for understanding the burgeoning rebellion in the U.S. workplace. Ranney captures well the appeal of Chicago:

The area I worked in during this period, Southeast Chicago and Northwest Indiana, included one of the largest concentrations of heavy industry in the world. The region was anchored by ten steel mills, which, at their peak, employed two hundred thousand workers, half in Chicago. It has been estimated that for every steel job in the region there were seven other manufacturing workers, bringing the total number of employment to over one-and-a-half-million workers.

Greater Chicago was, and remains, the transportation hub of the United States. Yet Ranney didn’t get one of the coveted steel mill jobs. Employment had already leveled off in steel and was heading towards collapse. Instead, he found work in a variety of factories in the Chicago area. By far, the most important was his experience at Chicago Shortening.

Chicago Shortening was one of those small, obscure, but essential twigs, sprouting from the long branches of U.S. industry. Located on the far Southside of Chicago, it specialized in making hydrogenated fats used in the food products of major corporations like Keebler Cookies and M&M’s. In keeping with manufacturing essential ingredients for some of the favorite snack foods in the U.S., Chicago Shortening products were highly unhealthy, and the waste products were equally destructive to the environment.

Ranney answered a local newspaper ad for a maintenance job at the Chicago Shortening plant. Right away he picked up an uncomfortable vibe from management, and several coworkers. Why did he have to take a test for a maintenance job? He later found out it was to keep Blacks out of the plant. The first worker he was introduced to, Bob Fulton, the plant engineer, was a white pipefitter, who said without any shame, “Thank God you finally brought a white guy in, Bob. I was afraid you were gonna hire one of them n*****s.”

This was Ranney’s introduction to the brutal racial and job classification hierarchy at Chicago Shortening. Blacks and Latinos were confined to the dirtiest and most dangerous jobs, while whites held the most skilled. The shop floor even came complete with an Iron Cross wearing, Nazi plant worker named Heinz! Workers of different races and nationalities frequently regarded each other with varying levels of suspicion or outright hostility.

It took Ranney a while but he eventually became good friends with several of the workers. The people Ranney became closest to had important back-stories and hidden talents, such as Charles, a longstanding black employee, who was a talented artist. Though several seemed “touched” by the radicalism of the era, none of Ranney’s coworkers at the plant were organized socialists.

Strike

One potentially redeeming virtue for workers at Chicago Shortening was that there was a union. Unfortunately, it was a corrupt little bargaining unit of the Butcher Workmen. According to Ranney, it was mobbed up and in bed with the company. It was also pretty useless, especially when it came to dangerous working conditions. Two examples include Ranney being severely injured when high-pressured, super-heated water burned his face, and when his buddy Charles had his right hand crushed.

In 1978, an opportunity arose to fight for better conditions when the contract came up for renegotiation. Despite the corrupt nature of the local union, the leadership went through the motion of asking rank and file members to join a negotiating committee. This gave Ranney, Charles, and others, the opportunity to assert themselves as shop floor leaders, and make demands that exceeded those put forward by the union leadership.

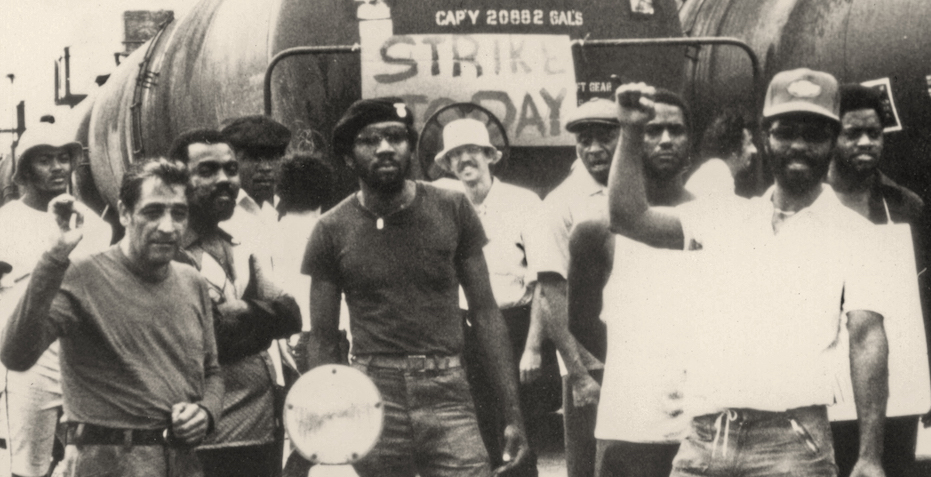

But the negotiations quickly went nowhere and the union was eager to squelch the “troublemakers” in the plant. Ranney was called to the office one day where he was assaulted by a union representative, who threatened to kill him. He stumbled from the office and his coworkers decided that they were going to walk out.

The strike was on. It was immediately declared illegal by the union and the company. The strike, however, took on a festive atmosphere, and Ranney recalled that the better selves of the workers came forward: “Women beg[an] coming to the [picket] line. They [were] bringing food. It turn[ed] into a big picnic.” Also, “there [were] [a] few six packs of beer around but no shake n’ bake and no reefer. No one [was] intoxicated! This pattern last[ed] for the duration of the strike.”

The strike went through many phases and drew support from a variety of sources, including radical Iranian students, and Puerto Rican independence activists. “The picket line…bec[ame] a school for a variety of political causes.” When management handed out a flyer red-baiting Ranney, one of the Mexican workers told him, “Almost all of us from Mexico are communists, so we are fine with you. The black workers are not bothered by the flyer.”

While there were ongoing battles with the courts, the company, and the union, fundraisers were held to support the strikers. But the penultimate event was when the strikers defied court orders and blocked a railroad engine from leaving Chicago Shortening in a tense confrontation with police and management. Charles was a real leader here. The railroad engineer, in frustration, declared, “No way I’m going to cross this picket.” Readers of the book will find this particular event of the strike as an example of how a picket line at an industrial workplace should work.

Eventually, however, the strike was lost. The workers were unable to hold out against the combined forces of the courts, the company, and the union. Despite his leadership in the strike, Chicago Shortening was forced to take Charles back, because he was out on workers’ compensation before the strike began. Charles taunted several of the scabs. Tragically, one would eventually stab and mortally wound him.

Strange feeling

Ranney went to work at several other industrial workplaces on the Southside of Chicago after he left Chicago Shortening, but he eventually returned to university teaching. He learned many lessons from his workplace experiences, but he always had this “strange feeling” during his interactions with fellow workers of “being on the outside looking in,” and at the same time, of being on the “inside looking out.” This seemed to be an irresolvable conflict, but it didn’t get in Ranney’s way of developing a great bond with many of his coworkers. At the same time, he also felt that he had options that they never would.

He drew many lessons from his years working on the Southside of Chicago, and one of the most important was acknowledging the role of racism within the working class. “When I began doing factory work, I discovered that I was naive about the extent of the raw racism within the working class. I saw firsthand how a racial division of labor was both the keystone and mortar of the U.S. factory system.”

Another involved his own role in the conflicts between workers and the company:

Because of my own dual status I tried to be careful not to initiate actions that would put others in jeopardy. But at the same time, I also tried my best to be supportive of those willing to take risks and to reinforce and expand on the best of the ideas and visions to come from people when they are in struggle.

One of the deeper political lessons for Ranney was the international solidarity that existed between black workers, which flowed from their own struggles:

Black workers’ stark experience with both class and racial oppression on the factory floor, combined with [the] rising civil rights movement, meant that they were attracted to other movements around the world led by people not classified as ‘White.’ The dual class and race oppression in the past enabled them to play a leading role in resisting both company and the union during the contract dispute.

A few disagreements

I have a few disagreements with Ranney. I think he discusses manufacturing in the United States as if it all went overseas. Labor historian Kim Moody has addressed and roundly debunked this contention in many places. At the center of manufacturing is the logistics industry, which in many ways has reorganized the industrial working class back into the huge workplaces that have been thought long gone. I think socialists doing trade union work always need a perspective to guide them, even in small workplaces.

“One might ask from the vantage point of 2019 whether our efforts some forty years ago made a difference,” Ranney writes:

It is an impossible question to answer in these terms. As I write this, I am seventy-nine years old and will likely never know whether these insights have been passed along to a new generation of workers or radicals who can build on the collective insights of my generation and keep the struggle for a new society alive. But it is my hope, and that is why I think our efforts were worthwhile.

David Ranney is professor emeritus in the College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs at the University of Illinois Chicago. Ranney has also been a factory worker, a labor and community organizer, and an activist academic. He is the author of four books and more than a hundred journal articles, book chapters, and monographs on issues of employment, labor and community organizing, and U.S. trade policy. His two most recent books are Global Decisions, Local Collisions: Urban Life in the New World Order and New World Disorder: The Decline of U.S. Power. In addition to his writing, he gives lectures on economic policy and politics and also finds time to be an actor and director in a small community theatre.