By Ariella Markowitz, Amanda Font

KQED

September 26th, 2020

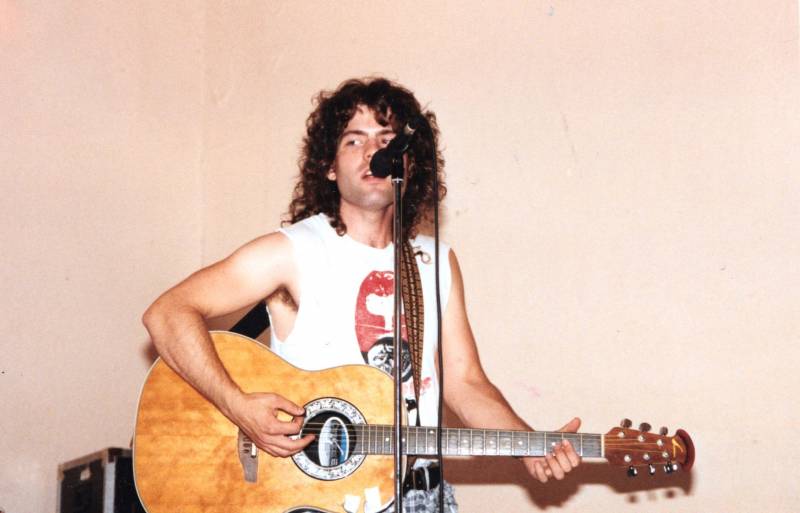

Musician Ian Brennan was born in Oakland and made a name for himself performing in live shows at the Brainwash Laundromat in ‘90s San Francisco. He went on to become a producer, working with artists like Lucinda Williams and Ramblin’ Jack Elliot.

But Brennan is best known for his field recordings. Along with his wife, photographer and filmmaker Marilena Delli, Brennan has recorded musicians around the world, like the inmates at Zomba Prison in Malawi and genocide survivors in Cambodia. He won a Grammy Award for the production of the album Tassili from the band Tinariwen, which has roots in Mali and Algeria.

More recently, Brennan has worked closer to home, producing an album called Homeless Oakland Heart in 2019, which features recordings of unsheltered people on the streets of West Oakland — singing, rapping, reciting poetry and playing instruments, including a broken, nylon-string guitar one man had in his tent.

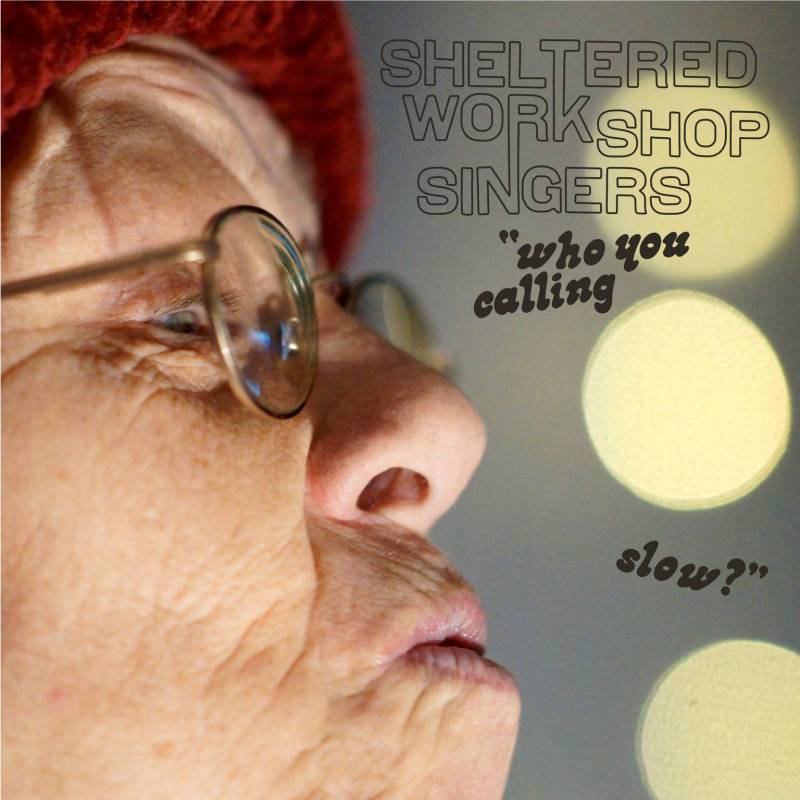

Now, Brennan has turned his mic on his older sister, Jane Brennan, who was born with Down syndrome. She and her companions at an adult care facility in Contra Costa County call themselves “The Sheltered Workshop Singers.” They released their first album, “Who You Calling Slow?” this month.

Brennan sat down recently to talk with California Report Magazine host Sasha Khokha about recording the album. Here are some highlights.

Comments have been edited for brevity and clarity.

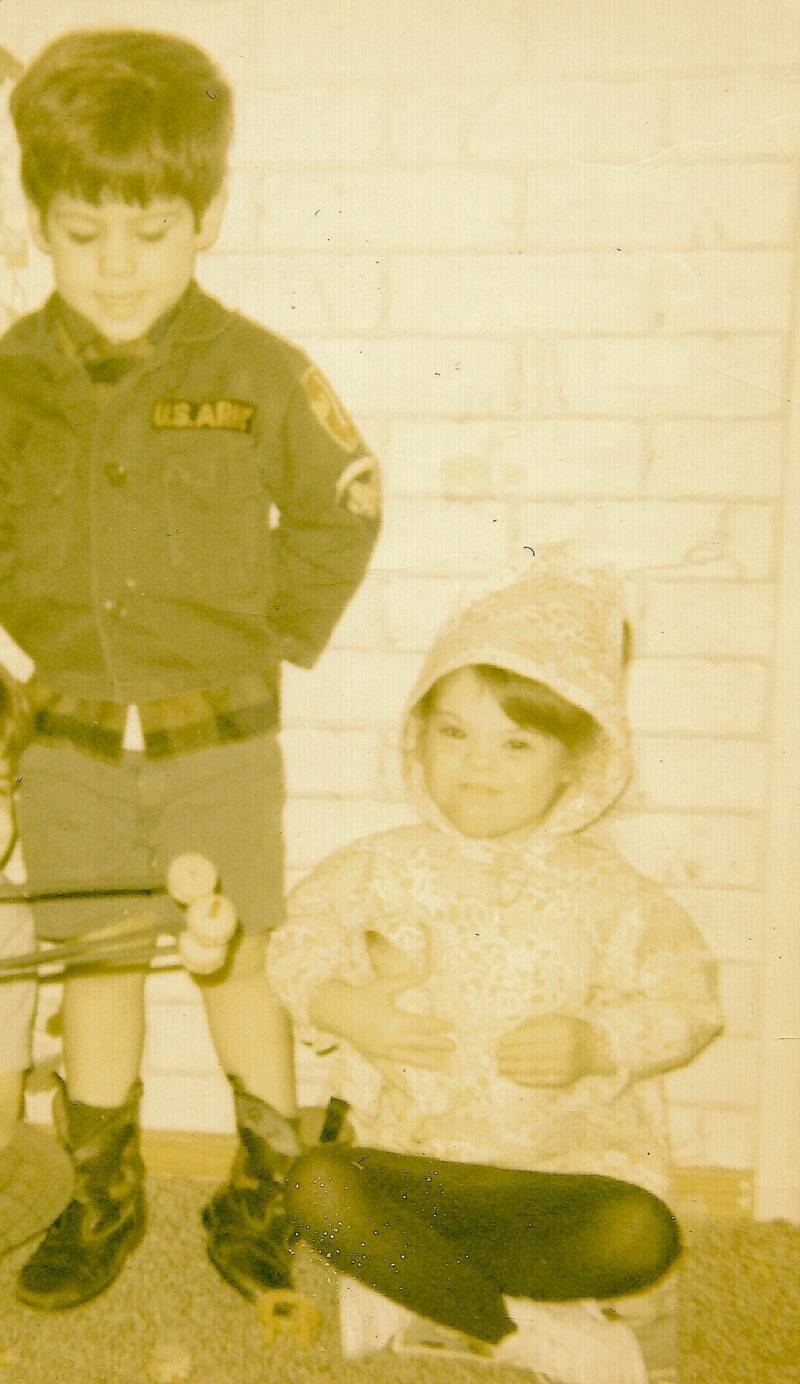

On Growing Up With Jane

Jane was and is one of the biggest factors in my life. The most significant individual growing up really in my whole world was her. We’re only 14 months apart. And for better or for worse, she took care of me and she took care of the rest of us and the family. And it was because of her that we that we stayed together as a family. I don’t know that we would’ve made it without her.

I started playing guitar when I was five. I don’t really remember not playing music. I only really remember music as a part of everyday life, as a way to connect, a way to communicate. For my sister and her peers, it was dance — the freedom that they express themselves with — was always so extraordinary. ‘We used some of the singers’ own devices — the wheelchairs, the canes. There was a yoga ball. It’s 100% live.’Ian Brennan, music producer

Jane has old vinyl records of mine and some other folks. And she’s played those records until they’re unplayable or continues to play them when they’re barely playable. I’d say she’s, with great certainty, the only person left on the planet Earth, if ever there were many, that listens to any of my music. She still embraces it. I think for her, probably a lot of it is the memories that surround the music.

On Jane’s Musical Abilities

Well, my mother played a little piano as part of her therapy, but Jane would play it and she would bang away on it — again, without any reservation. Music was our language of communicating with one another. I was verbal before my sister was verbal, though she was older. She taught me a way of listening: to listen not to the words, but the spirit.

The beautiful thing about her is that she is mostly nonverbal, but she knows the words to every song — she just makes them up as she goes along. And there’s not that self-consciousness. It’s not a performance. It’s instead just an expression of her state.

If we listen to each other more carefully, we learn and we have so much to learn from each other. What I learned from my sister is that she may be developmentally delayed, yet her emotional intelligence is higher than almost anybody I’ve ever met.

On Producing ‘Farewell Father’

We had an idea about doing a recording with Jane and her peers for years. My father was 85, and we realized that if we were going to do it, we needed to do it now. My father had been diagnosed with less than a year to live. Jane is now 55. The life expectancy, unfortunately, for her generation with Down syndrome is 60.

We did the recordings with three generations — my three-year-old daughter and my father were present. So were Jane and her peers, many of whom I’ve known their entire lives. On the song “Farewell Father,” you can hear Jane singing to my father and telling him goodbye. And, in fact, he passed away two months later. Sponsored

On Recording His Family After Recording Around the Globe

It felt like literally coming home. It really came full circle musically because the music for me really started with her. It’s been deeply rewarding to hear those voices and to see that there are no amusical people. Music is everywhere. It’s necessary for survival.

I really evaluate a record based on: is it unique? Is it different? Does it have a reason to exist for that reason alone? I think that the voices here are unlike any others. The things that are expressed are real. This recording is comprised of instant compositions with people that had never written songs before, sung into a microphone before or played instruments before. Nonetheless, the results were stunning.

On the Recording Techniques Used

We used some of the singers’ own devices — the wheelchairs, the canes. There was a yoga ball. It’s 100% live. What you’re hearing is something that happened.

On most recordings nowadays, what we hear is something that never happened. It’s a simulation of an event that never actually occurred. I am invested in trying to represent a place and time and a moment in time that can connect people to reality in such a way that they can hear better.

On the Album’s Message

What I’ve always learned from Jane and her peers throughout my life is perseverance and tenacity and acceptance. It’s not a surrender, but an acceptance of limitations, working with them and beyond them.

People on this album make up these incredible melodies that are very intricate and unique and complex. Some people have heard them and they say, “What language is that in?” And it’s easy. It’s in the language of music. It’s the universal language. There are no words to those songs. The meaning is embedded in the music itself.

Ian Brennan is a Grammy-winning music producer who has produced three other Grammy-nominated albums. He is the author of four books and has worked with the likes of filmmaker John Waters, Merle Haggard, and Green Day, among others. His work with international artists such as the Zomba Prison Project, Tanzania Albinism Collective, and Khmer Rouge Survivors, has been featured on the front page of the New York Times and on an Emmy-winning 60 Minutes segment with Anderson Cooper reporting. Since 1993 he has taught violence prevention and conflict resolution around the world for such prestigious organizations as the Smithsonian, New York’s New School, Berklee College of Music, the University of London, the University of California–Berkeley, and the National Accademia of Science (Rome).