By Mike Tidwell

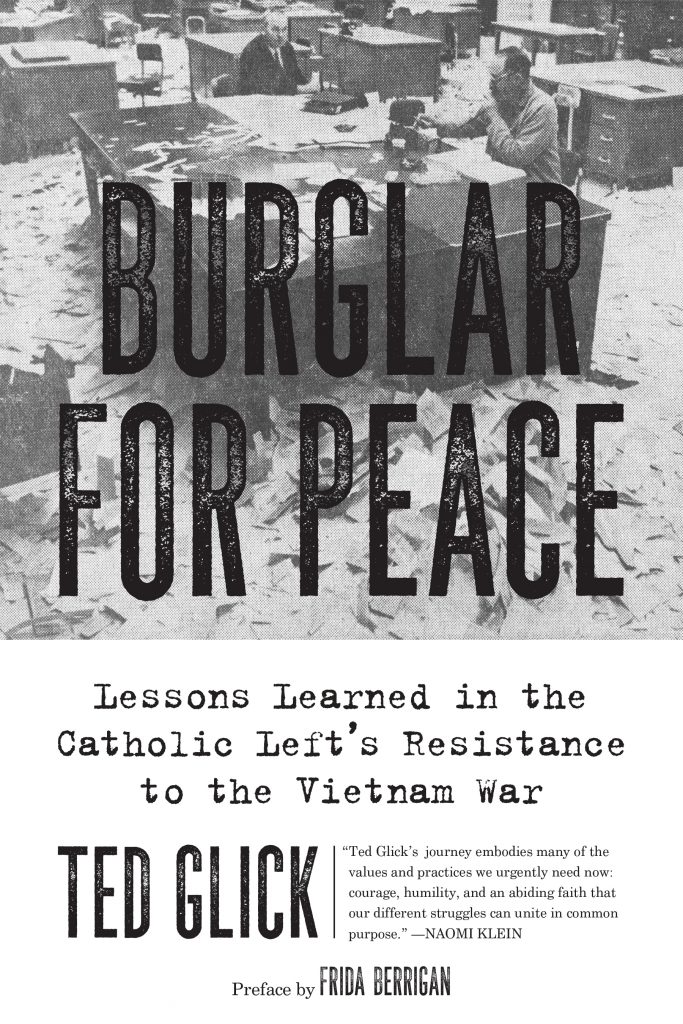

A review of Ted Glick’s “Burglar for Peace: Lessons Learned in the Catholic Left’s Resistance to the Vietnam War”

Ted Glick is a legend within the American climate movement. He’s occupied ledges and dropped banners above climate-denying federal agencies. He’s fasted for long periods — once for 42 days — to draw attention to social injustices, including global warming.

These are just a few examples of a man’s life dedicated to “disruptive nonviolence” for a higher purpose. In May 1969, at the age of 19, Glick dropped out of college and returned his draft card to the Selective Service, refusing to kill his “Vietnamese brothers.” In 1970, he went to federal prison for 11 months for breaking into draft board offices and destroying draft records. In prison, he was deeply moved — and forever changed — by the disproportionate incarceration of blacks and the systemic discrimination he saw within the prison hierarchy itself.

Now a veteran leader at the group Beyond Extreme Energy, Glick — who is white — was nonetheless the first person to send me a “defund the police” email after the death of George Floyd.

All of which is to say Glick’s new autobiography “Burglar for Peace” is not just a dramatic and eminently readable personal story of war resistance. It chronicles, through Glick’s life, the arc of resistance on most of the biggest social issues of our time, including — presciently — the Black Lives Matter protests now.

The subtitle of the book is “Lessons Learned in the Catholic Left’s Resistance to the Vietnam War.” Those lessons include a commitment to “high risk” actions that are nonetheless totally nonviolent — and therefore very powerful. Glick writes, “I hope and pray that my writing this book…(will help us) create a world based on justice, equal rights, a deep connection to the natural world, and active love.”

I had the pleasure of working with Ted Glick for about a decade at the Chesapeake Climate Action Network. While technically his boss, I always felt like Glick’s student, in awe of his personal history and hard-earned skills. By the time I met him in 2005, he was not deeply religious. But I have never met a more consistently kind and kind-hearted human being. In ten years I never heard Ted say anything negative or personally critical toward another staff member or others in the broad and often fractious climate change movement. Not once.

But make no mistake, Glick is and has always been a social-justice bad ass. Over the course of these 200 fast-moving pages, Glick chronicles a life of making “good trouble,” as Congressman John Lewis says. After hearing Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. speak in the mid 60s, Glick anguished over his privileged life as a freshman college student in Iowa while the world burned around him. A highlight of the book is a multi-week exchange of letters between Glick and his parents in New York State. They are shocked that he is considering dropping out of school to organize against the war. But, in a foreshadowing of the persistent lifelong activism to come, Glick uses a mix of facts and anecdotes and philosophy and religion to educate his folks. Then he takes the next big step. He finally wins them over with his personal commitment and sacrifice. He drops out of school, exposes himself to the draft, and devotes his entire being to stopping the war.

Much of the rest of the book chronicles Glick’s journey to the inner circle of the Catholic Left, led by the famous anti-war brothers, Philip and Daniel Berrigan of Baltimore. Glick masters the suspenseful art of breaking into Selective Service offices, usually entering during regular business hours then hiding in a closet with food and a Bible until nightfall, then letting other “burglars for peace” into the office. They would then gather and later destroy all the draft records they could find before sunrise.

This works until it doesn’t. Glick and seven colleagues are caught on September 6th, 1970, in Rochester NY. Facing felonies, they decide to stage their own defense before a judge and jury. Glick’s retelling of the trail represents the book’s apex, featuring dramatic verbatim testimony where Glick, under oath, plays the role of questioning the other defendants. They describe the horrors of the Vietnam War and their religious and spiritual duty to sacrifice their own freedom and well-being for the sake of the innocent. “Hope it makes a difference in your lives,” one defendant tells jurors as the trial concludes with guilty verdicts.

That simple line summarizes why social and environmental activists worldwide do what they do, of course. A desire to make a difference, to change lives for the better. After serving 11 months in prison, Glick decides to broaden his activism to building a movement that is more than just anti-war. In a public falling out with Catholic Left leader Philip Berrigan, Glick declares that he is publically moving “away from simplistic views of violence and war and toward an understanding of class, sex, and race” as the foundations of most social wrongs. He winds up organizing in places as disparate as East Harlem and Wounded Knee, South Dakota.

Later, in 1992, in an act that best demonstrates the prophetic nature of much of Glick’s career, he engaged in a punishing 42-day water-only fast to protest the federal holiday celebrating Christopher Columbus. He wrote at the time that he and other fasters were “calling for an open acknowledgement of the devastation to Native and African peoples and the environment that began with Columbus’s arrival in the Americas.” Fast forward to July 2020 and we see activists toppling a statue of Christopher Columbus in Baltimore and throwing it into the Inner Harbor. Those “radical” seeds had been planted 28 years earlier.

By 2003, Glick’s career pivoted completely to climate activism following the horrific European heat wave that claimed at least 35,000 lives. “I understand that there are other very important issues, and that there are often interconnections among them, but the fact is that there is a definitive time urgency to the climate issue,” Glick writes. “There are climate tipping points after which it will be extremely difficult for humanity to recover from the devastation we have caused. If human society does not rapidly shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy and serious energy efficiency in addition to other actions to protect and sustain our natural environment, we face a disastrous future.”

Ted now brings to the climate movement many of the tactics he learned during his Vietnam resistance. He organizes disruptive protests at the meetings of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, a rogue body that is radically pro Trump and pro fossil fuels. Activists stand up one at a time, minutes apart, to loudly object at hearings, turning the meetings into spectacles. The same tactic was used by Glick in 1974 when, obscenely, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger was given a “peace” award before a crowd of thousands in DC. Today, Kissinger is widely viewed as a war monger. And today, FERC is increasingly known as a reckless, illegitimate outfit ripe for overhaul. Thank you Ted Glick.

But perhaps the biggest single lesson of the book, again, is that black and brown lives really do matter. We cannot solve the climate crisis without environmental justice, Glick writes. Published before the murder of George Floyd, the book includes in its final pages a passage on “Unlearning White Supremacy.”

“Burglar for Peace” is a thoughtful, intense, and ultimately satisfying account of an activist life lived well. It’s a life that has made a difference in my own life and that of so many others, including millions who will one day live free of climate ruin and senseless wars — hopefully — because of Glick’s sacrifices and inspiring labor for so many decades.

(Mike Tidwell is founder and director of the Chesapeake Climate Action Network. He is the author of six books of nonfiction, including “Bayou Farewell: The Rich Life and Tragic Death of Louisiana’s Cajun Coast”)

Ted Glick is the author of the forthcoming Burglar for Peace: Lessons Learned in Catholic Left Resistance to the Vietnam War. Past writings and other information can be found at https://tedglick.com, and he can be followed on Twitter at https://twitter.com/jtglick.