By Ian Brennan

The Guardian

September 17th, 2020

Through my sister Jane, who has Down’s syndrome, I learned how to listen not just with my ears but my entire being

I grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area with my only sister, Jane, who has Down’s syndrome. We are just 14 months apart. She was born premature, her weight dropping after birth to less than four pounds. The doctors sent her home to die: that’s what they did with kids like her back in the 1960s. But she defied and even thrived.

Growing up, my sister – unable to contain her oversized tongue – steered her eyes down sideways and hard from the shame. I witnessed her discomfort too many times to not remain vigilant, playing defence for a lifetime. I inherited little choice but to side with those marginalized.

Our town was almost entirely lacking in diversity, and people with disabilities were shuttered and rarely seen. Many people stared and pointed at her. Others snickered or laughed. Some even hurled the “R” word. Whether under breath or out loud, it was the one trigger that could belie my sister’s otherwise gentle and loving nature. She’d growl under her breath, “Not a retard. Not a retard. Retard, no!”

Although Jane is nearly nonverbal, she is multilingual. She knows the words to almost every song. She just joins in and makes them up as she goes along.

As children, our main connection was through music – joy expressed through dance, sadness and longing with melody. Jane taught me a different kind of listening. Not so much with the ears, but the spirit, with your entire being.

Never have I witnessed more unselfconscious bodily expression than decades spent at Friday rec-center DJ nights with her and her community’s peers. The electricity and abandon overflow, the given soundtrack merely secondary – any tune will do. The group expressiveness puts drug-fuelled ravers in Ibiza or disco-era Studio 54 to shame.

The prejudice against people with disabilitytraverses frontiers and permeates most cultures. Fortunately, those facing physical limitations have demanded and made tremendous progress in accessibility throughout the industrialized world. But the developmentally and intellectually disabled are often left voiceless, due in large part to their often genetically impacted speech abilities.

The childhood love of music I shared with Jane spilled over into adulthood, into my career as a musician and producer. For the past decade I have travelled the world – from Malawi to South Sudan, Romania to Cambodia – with my wife, the photographer and film-maker Marilena Umuhoza Delli, making field recordings and producing albums that provide a platform for original music from under-represented regions and languages. We often work with persecuted or ostracized populations, including those with albinism in Tanzania, elderly women accused of witchcraft in Ghana, and Tuareg rockers Tinariwen (an LP we recorded in the Algerian desert won a Grammy for best world music album).

Earlier this year I returned to my home town to produce a record that is possibly my most personal work yet. I travelled east of the San Francisco Bay, to an aged strip mall that shares a parking lot with a doughnut shop, a liquor store and a sketchy massage parlor. There resides a weekday program for dozens of adults with varying cognitive and ambulatory abilities, including my sister Jane.

Who You Calling Slow? was made alongside Jane and her sheltered workshop peers and is reportedly the first album released that spotlights the developmentally disabled population. The recordings were made with the involvement of my father, Jim, during his final stage battling cancer. With my sister having pushed well past 50, the precipitous approach to her estimated life expectancy had begun to manifest in diminished orientation, expressiveness and hearing. We knew that if this long-envisioned collaboration was to happen, the time was at hand.

A diverse group of more than 20 individuals participated in the album, ranging in age from early 20s to 60s. More than half were women. Many were in wheelchairs or used crutches, canes and braces to walk. None had sung into a microphone before or held a stringed instrument.

The recordings with the Sheltered Workshop Singers – all based on improvisations – were set up in a narrow, plasterboard-walled room with throbbing lights and a disco ball, a place designed to have a paradoxically calming effect on some participants.

The instrumentation mostly came from their immediate environment – a walker used as a cowbell, a deflated yoga ball for a bass drum, and the polyester floor itself banged and stomped.

There are few more expressive singers than those who are nonverbal. Possessing limited vocabulary dams up feelings, particularly when what few words can be mustered often remain misunderstood or ignored.

Making the recordings, one woman’s only liability was her own prolificness. Grace reportedly spends hours a day isolating and consoling herself with song. While beholding her self-serenades, the limitations of the recording process were laid bare. We could only hope to catch the moment, but not the eternal place from which the music was born.

Another woman, Janet, sang from her wheelchair of fearlessness, repeatedly declaring, “I’m not afraid of anything.” Unlike most such macho boasts that usually ring hollow, there was no doubting her ownership of the phrase. Her courage was a matter-of-fact claim.

My sister was present for every tune recorded and she joined in group collaborations like the kazoo orchestra. She also featured on the track Farewell Father (I Love You), a song in which she attempts to tell our father goodbye.

Immediately after completing the recordings, I left for Italy but became stranded there due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Not long afterwards my father began to fade andI

organised Jane a ride over to see him one last time. The reunion took

place just hours before he passed. Immediately after Jane’s visit, the

nurse said my father grew solemn and, after a few contemplative moments,

began to transition from this life. There is a certain poetry in a

daughter – who was sent home to die as an infant (at the doctor’s

direction) – being the one who 55 years later helped her father make

peace with his own death.

• Who You Calling Slow? by the Sheltered Workshop Singer is out on 18 September. Profits from the album go to the Arc of the United States

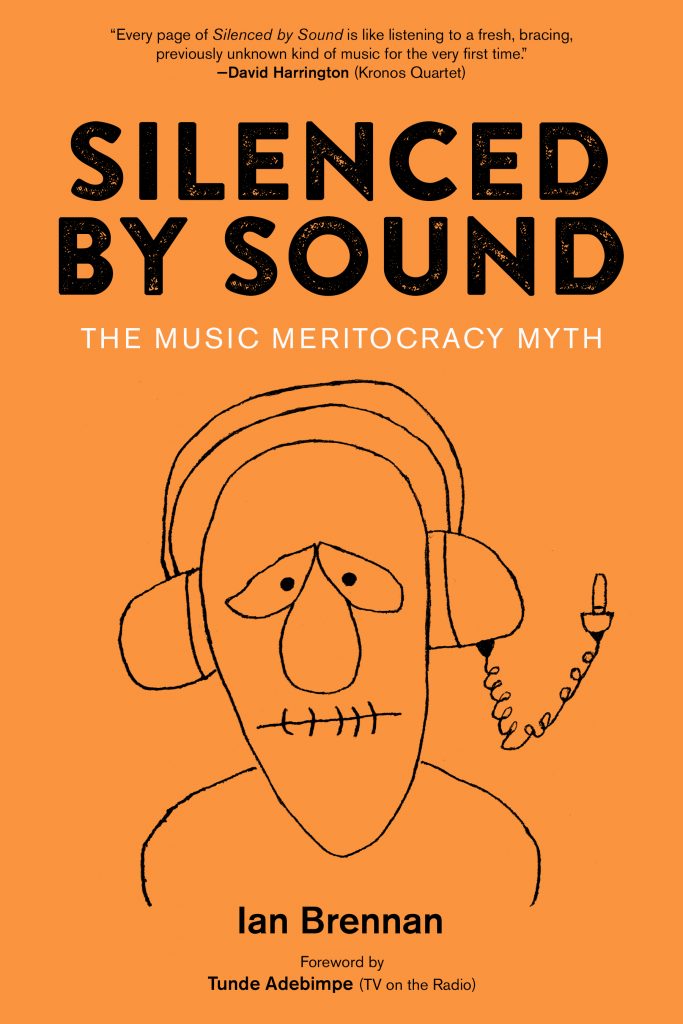

• Ian Brennan is a Grammy award-winning music producer and an author and lecturer on violence prevention. His latest book is Silenced by Sound: The Music Meritocracy Myth

Ian Brennan is a Grammy-winning music producer who has produced three other Grammy-nominated albums. He is the author of four books and has worked with the likes of filmmaker John Waters, Merle Haggard, and Green Day, among others. His work with international artists such as the Zomba Prison Project, Tanzania Albinism Collective, and Khmer Rouge Survivors, has been featured on the front page of the New York Times and on an Emmy-winning 60 Minutes segment with Anderson Cooper reporting. Since 1993 he has taught violence prevention and conflict resolution around the world for such prestigious organizations as the Smithsonian, New York’s New School, Berklee College of Music, the University of London, the University of California–Berkeley, and the National Accademia of Science (Rome).