By George Lakey

Waging NonViolence

June 11th, 2013

The history of training is a history of playing catch-up — but now’s the time for us to get a head start.

As I write this dozens of trainers in Philadelphia near completion of a 17-day intensive called the “Super-T,” a kind of boot camp for trainers. In the 1950s, there was no place I could go to learn this kind of activist facilitation training, even though Paulo Freire was doing groundbreaking work in his “pedagogy of the oppressed” and the Gandhi-influenced Muslim leader Abdul Ghaffar Khan had used training to prepare his Pashtun nonviolent army for combat with the British Empire.

We’ve come a long way since the 1950s, when the civil rights movement was being seeded by Congress of Racial Equality trainings in church basements and Rosa Parks attended workshops at the Highlander Center in Tennessee. Now even advanced training for activist trainers is available. Training for Change, an organization I co-founded, has led over 20 Super-Ts. These facilitator marathons have attracted activists from dozens of countries on five continents.

I’m grateful that today’s teenagers don’t need to get lucky and find a mentor, as I did by apprenticing to Charlie Walker in the 1950s. Today the Ruckus Society, Seeds of Peace UK, Pace e Bene, the Centre for Applied Non Violent Actions and Strategies — that is, CANVAS — and many other training organizations exist to help people gain skills. Training organizations in turn use Training for Change to upgrade their own skills and work collaboratively on projects like the Global Power Shift this week in Istanbul. We’ve made major progress just in my lifetime, but much more is needed to meet the multiplying opportunities for change.

Why more training now?

The history of training is a history of playing catch-up. Very few movements seem to realize that the pace of change can accelerate so rapidly that it outstrips the movement’s ability to use its opportunities fully. In Istanbul a small group of environmentalists sit down to save a park, and suddenly there are protests in over 60 Turkish cities; the agenda expands, from green space to governance to capitalism; doors open everywhere. It would be a good moment to have tens of thousands of skilled organizers ready to seize the day, supporting smart direct action and building prefigurative institutions. But excitement alone may slacken; as with the Occupy movement, spontaneous creativity has its limits.

With the right skills, movements can sustain themselves for years against punishing, murderous resistance. The mass direct action phase of the civil rights movement pushed on effectively for a decade after 1955. Mass excitement doesn’t need to fizzle in a year. A movement thrives by solving the problems it faces.

Anti-authoritarians don’t want to count on a movement’s top leaders to be the problem-solvers, but instead to develop shared leadership by fostering problem-solving smarts at the grassroots. There’s nothing automatic about grassroots problem-solving. How well people strategize, organize, invent creative tactics, reach effectively to allies, use the full resources of the group and persevere at times of discouragement — all that can be enhanced by training.

Nothing is more predictable than that there will be increased turbulence in the United States and many other societies. Activists cause some of the turbulence by rising up; other turbulence results from things like climate change, the 1 percent’s austerity programs and other forces outside activists’ immediate control.

Increased turbulence scares a lot of people. It’s only natural that people will look around for reassurance. The ruling class will offer one kind of reassurance. The big question is: What reassurance will the movement offer?

When students in Paris in May 1968 launched a campaign that quickly moved into nationwide turbulence, with 11 million workers striking and occupying, there was a momentary chance for the middle class to side with the students and workers instead of siding with the 1 percent. The movement, though, didn’t understand enough about the basic human need for security and failed to use its opportunity. That was a strategic error, but to choose a different path the movement would have required participants with more skills. Training would have been necessary. We can learn from this, inventory the skills needed and train ourselves accordingly.

What is training ready to do for us?

Here are a few of the key benefits that we should expect to gain from one another through training:

1. Increase the creativity of direct action strategy and tactics. The Yes Men and the Center for Story-Based Strategy lead workshops in which activist groups break out of the lockstep of “marches-and-rallies.” We need to have a broad array of tactics at our disposal, and we have to be ready to invent new ones when necessary.

2. Prepare participants psychologically for the struggle. The Pinochet regime in Chile depended, as dictatorships usually do, on fear to maintain its control. In the 1980s a group committed to nonviolent struggle encouraged people to face their fears directly in a three-step process: small group training sessions in living rooms, followed by “hit-and-run” nonviolent actions, followed by debriefing sessions. By teaching people to control their fear, trainers were building a movement to overthrow the dictator.

3. Develop group morale and solidarity for more effective action. In 1991 members of ACT UP — a militant group protesting U.S. AIDS policy — were beaten up by Philadelphia police during a demonstration. The police were found guilty of using unnecessary force and the city paid damages, but ACT UP members realized they could reduce the chance of future brutality by working in a more united and nonviolent way. Before their next major action they invited a trainer to conduct a workshop where they clarified the strategic question of nonviolence and then role-played possible scenarios. The result: a high-spirited, unified and effective action.

4. Deepen participants’ understanding of the issues. The War Resisters League’s Handbook for Nonviolent Action is an example of the approach that takes even a civil disobedience training as an opportunity to assist participants to take a next step regarding racism, sexism and the like. When we understand how seemingly separate struggles are connected, it helps us create a broader, stronger, more interconnected movement.

5. Build skills for applying nonviolent action in situations of threat and turbulence. In Haiti a hit squad abducted a young man just outside the house where a trained peace team was staying; the team immediately intervened and, although surrounded by twice their number of guards with weapons, succeeded in saving the man from being hung. Through training, we can learn how to react to emergencies like this in disciplined, effective ways.

6. Build alliances across movement lines. In Seattle in the 1980s, a workshop drew striking workers from the Greyhound bus company and members of ACT UP. The workshop reduced the prejudice each group had about the other, and it led some participants to support each other’s struggle. Trainings are a valuable opportunity to bring people from different walks of life together and help them work toward their common goals.

7. Create activist organizations that don’t burn people out. The Action Mill, Spirit in Action, and the Stone House all offer workshops to help activists to stay active in the long run. I’ve seen a lot of accumulated skill lost to movements over the years because people didn’t have the support or endurance to stay in the fight.

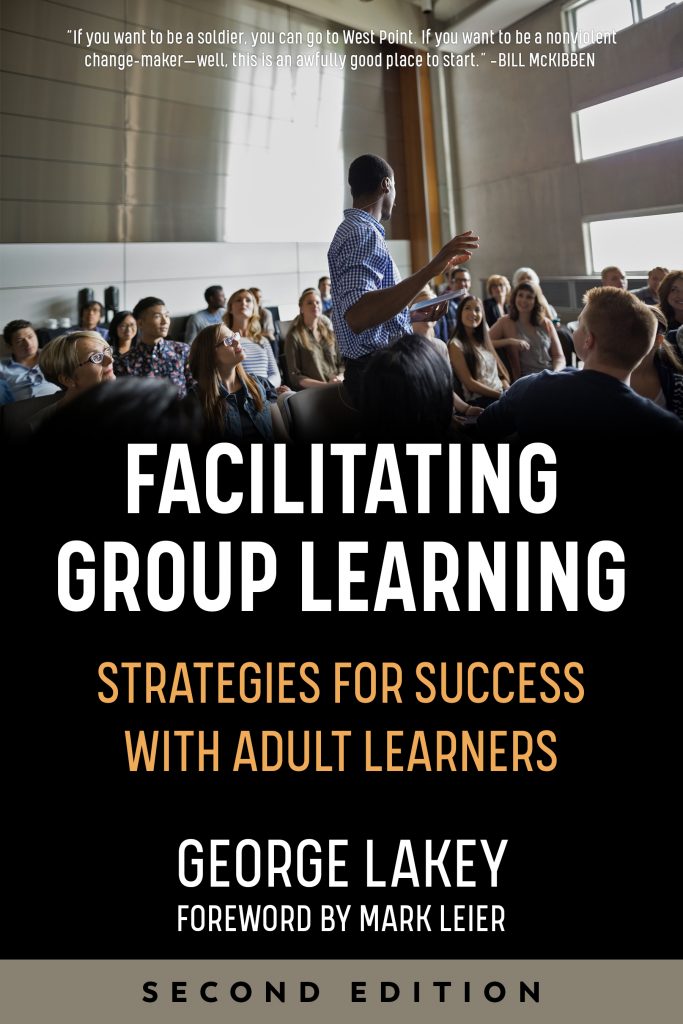

8. Increase democracy within the movement. In the 1970s the Movement for a New Society developed a pool of training tools and designs that it shared with the grassroots movement against nuclear power. The anti-nuclear movement went up against some of the largest corporations in America and won. The movement delayed construction, which raised costs, and planted so many seeds of doubt in the public mind about safety that the eventual meltdown of the Three Mile Island plant brought millions of people to the movement’s point of view. The industry’s goal of building 1,000 nuclear plants evaporated. Significantly, the campaign succeeded without needing to create a national structure around a charismatic leader. Activists learned the skills of shared leadership and democratic decision-making through workshops, practice and feedback. In my book Facilitating Group Learning, I share many lessons that have evolved from Freire’s day to ours.

I hope that readers of this column will add to the list of training providers in the comments, since I’ve only named some. My intention is to remind us that this could be the right moment, before the next wave of turbulence has all of us in crisis-mode again, to increase training capacity for grassroots skill-building. We’ll be very glad we did.

George Lakey has been active in direct action campaigns for over six decades. Recently retired from Swarthmore College, he was first arrested in the civil rights movement and most recently in the climate justice movement. He has facilitated 1,500 workshops on five continents and led activist projects on local, national and international levels. His 10 books and many articles reflect his social research into change on community and societal levels. His newest books are “Viking Economics: How the Scandinavians got it right and how we can, too” (2016) and “How We Win: A Guide to Nonviolent Direct Action Campaigning” (2018.)