Groups In Kansas And Missouri Inspired By Civil Rights Push

By Mawa Iqbal

Flatland

July 23rd, 2020

On a recent Wednesday evening Renee Maxwell was giving a presentation to about 15 people in front of the Boone County Courthouse in Columbia, Missouri. Soon that crowd doubled, thanks to protestors wrapping up their Black Lives Matter demonstration nearby.

“It was certainly the biggest audience we’ve had since we started doing these kinds of presentations,” Maxwell said.

Maxwell was hosting a “Path to Abolition” workshop, where she discussed ways community members could reallocate funds from local police and invest in other social programs. The talk was followed by a breakout session where attendees discussed specific ways they could reduce their reliance on the police in their everyday lives.

“Ask yourself, ‘Am I in imminent danger, or am I a harm to myself?’ If yes, then call the police,” Maxwell said. “But if no, then you’re better off calling on your neighbors… encouraging folks to talk to their neighbors.”

As the event concluded, attendees began filing out of the amphitheater in front of the courthouse, grabbing 8 to Abolition handouts on their way out. Maxwell was pleased to see some of them sticking around afterwards to ask questions.

“We were definitely seeing a lot more people who are involved with organizing protests having these conversations about police reform,” Maxwell said. “And even those who are not 100% on board with abolition can make more informed decisions about the kind of reform that they want to advocate for.”

Following the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police in late May, protests against police brutality continue to take place around the world, most recently focused on ongoing stand-offs in Portland, Oregon. In what some call the largest movement in U.S. history, Black Lives Matter has sparked a national debate on what role, if any, law enforcement should play in American society.

“The rest of my comrades are ready to capitalize on this historical moment,” Maxwell said. “These conversations are becoming more mainstream, and our city leadership is already talking about defunding the police, which, you know, a year ago would have been unheard of.”

Armed liberals

Maxwell and her “comrades” are part of the mid-Missouri chapter of the John Brown Gun Club, an armed, left-leaning social justice group based in Columbia. Much like its namesake abolitionist from the Civil War era, the group advocates for racial equity, among other issues such as the Second Amendment and LGBTQ+ rights.

While it is attracting growing interest from younger activists in the community, groups like the John Brown Gun Club have been advocating for the abolition of police and other forms of systemic injustice since its inception. Unlike most left-leaning groups, though, gun ownership is central to its strategy.

“They view themselves as keeping their right to arm, and to teach and protect others that they see as vulnerable,” said Teal Rothschild, professor of Sociology at Roger Williams University. “They are interested in Marxist ideals – of keeping the state ‘in check’ — and if necessary being prepared to overthrow the state – armed – to protect their rights.”

Rothschild wrote a dissertation last year on the Redneck Revolt, a national network of armed, anti-fascist groups. She noted their “enemy” isn’t the far right, but rather the system.

“Although BLM and other related movements now are largely peaceful, the connections between race relations and guns will continue as long as police violence, disproportionate rates of African Americans being incarcerated, and protests of racial inequality continue,” Rothschild said.

The mid-Missouri chapter of the John Brown Gun Club was founded in August 2017 in response to President Donald Trump’s inauguration, and as part of the Redneck Revolt coalition. The coalition itself was started in 2009, but after a brief hiatus reformed in 2016 by members of community defense groups in Kansas and Colorado.

Three years later, Redneck Revolt has dozens of branches all over the country, from Willamette Valley, Oregon to Homestead, Florida. These branches base their ideologies on a set of 11 organizing principles outlined on the Redneck Revolt’s website.

A hallmark of the Redneck Revolt and its branches is the use of firearms to support those principles. Its website includes calls for an armed community defense program in every community, in response to an “upsurge in reactionary and racist violence.”

That sentiment may be relevant now more than ever. According to a July report from the Brookings Institution, firearm sales soared at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in mid-March and again in early June amid the George Floyd protests.

During the first six months of the year, an estimated 10 million firearms were sold in this country. About 3.9 million of those firearms were sold in June alone, marking the highest monthly sales total since data collection began in 1998.

Note: Includes background checks for handguns, long guns, mixed transactions and other gun-related equipment. The government doesn’t track firearm sales, but it does track background checks that are required to buy guns from licensed dealers.

Source: FBI/NICS Firearm Background Checks

“The protests faded but, as public discussions about Black Lives Matter and defunding the police persisted, firearm sales remained elevated throughout the month of June,” the Brookings report said.

Firearms are a big part of the mid-Missouri chapter of the John Brown Gun Club. While most of its projects are centered around advocating for marginalized communities, the club offers community range days at a local conservation area.

Dirk Burhans has been a member of the club for two years. He said the range days are a great way to learn firearm safety in a welcoming, inclusive environment.

“We certainly do train people on how to use firearms, especially women and minorities,” Burhans said. “I think that’s something that I would like to expand into.”

And while the pandemic has interrupted range days for now, Burhans is looking to potentially work with another armed, leftist group in the area on firearm training.

“Within the last year there’s been a new gun club in Columbia called Sharp End,” Burhans said. “They’re a Black gun club, and our group is mostly White, so we hesitate to plow into that territory without being asked. But it’s very much something we want to work toward.”

Shifting gun culture

The practice of arming marginalized communities is nothing new. According to Professor Chad Kautzer, the Deacons of Defense and Black Panther movement were both Black civil rights groups from the 1960s who armed themselves.

“I think it’s more pronounced and widespread today, the various kinds of left groups arming themselves,” Kautzer said. “But they are certainly part of a tradition.”

Kautzer is a philosophy professor at Lehigh University, with an emphasis on how race and gender interact with other identities, political and economic structures. He said the recent resurgence of leftist gun groups could be because of a shift in American gun culture.

“The National Rifle Association has transformed from an organization that’s about marksmanship, competition and hunting, into a political organization that’s supposedly about patriotism,” Kautzer said. “This has contributed to a militarizing whiteness over the last several decades, and that’s where we’re at now.”

Kautzer said the emergence of leftist gun clubs is a defensive reaction to a conservative culture that has been arming itself since the 1960s. In his view, that is when American gun culture started to become synonymous with American conservatism.

Law Professor Adam Winkler specializes in gun policy at UCLA, and is the author of “Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms.” He said that trend contradicts what the Second Amendment is all about.

“The Second Amendment talks about a well-armed militia defending itself against tyranny,” Winkler said. “So, the NRA should be protecting Black Lives Matters protestors against tyranny, but instead they are on the side of the police.”

Given that right-wing groups have more guns, Winkler said groups such as the John Brown Gun Club are stepping in to make sure the left is armed as well. Even so, he downplayed the risk of open conflict.

“(Leftist) groups are still on the fringes, and guns on the left are relatively exceptional,” Winkler said. “So the possibility of these two groups fighting each other is small.”

Judy Sherry, however, doesn’t want to take that risk.

“Protesting and demonstrating is a First Amendment right,” Sherry said. “But there will be more deaths. So far they have just brandished their weapons, but I am not a big believer in using guns. That’s not the way you settle conflicts or make decisions.”

Sherry serves as president of local gun control group, Grandparents Against Gun Violence. She said there are many states that have passed legislation to ban assault rifles and close gun show loopholes.

“I think the country is way ahead of the legislators, and that is because the legislators are bought and paid for by the NRA,” Sherry said.

For it’s part, the NRA portrays itself as “a major political force and as America’s foremost defender of Second Amendment rights.” On March 21, just as pandemic-forced lockdowns began, the NRA’s official Twitter account declared, “Americans are flocking to gun stores because they know the only reliable self-defense during a crisis is the #2A.”

While the NRA pushes firearms for individual self-defense and security, Kautzer said leftist gun groups typically encourage a group identity.

“This identity has made them vulnerable to right-wing gun violence, so communities of color, LBGTQ+ communities, poor, lower-income communities who all experience organized, hate-fueled violence,” Kautzer said. “Fighting back, in this case, is actually challenging that bigotry. This is where the liberatory element comes from.”

In practice, collective protection can look something like appointing certain neighbors to a community watch group instead of relying on local police, or even defending property theft during a time of natural disaster.

The liberation focus, however, is key, according to anarchist and speaker scott crow, who styles his name in all lowercase letters. As someone who worked with founding members of the first John Brown Gun Club in Lawrence, Kansas, he had been developing the concept of armed community defense since the group’s formation in 2004.

“It’s just liberatory approaches to everything,” he said. “Guns do have an important place in community defense. And that communities need to decide that for themselves if there’s a place and a time for that when they need them.”

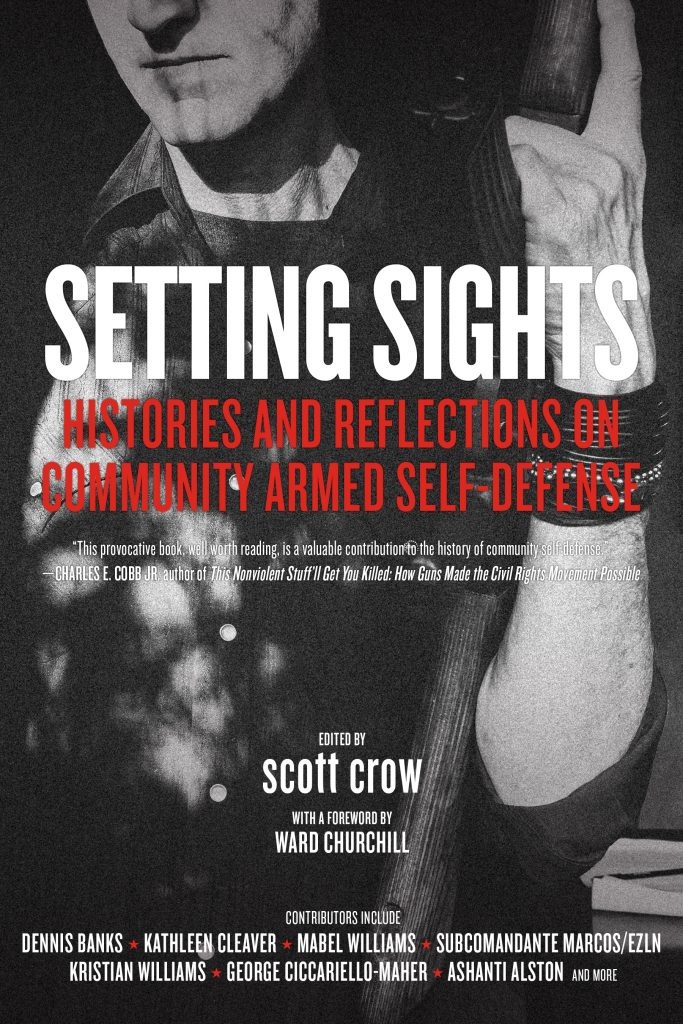

He then put these ideas into his 2018 book, “Setting Sights: Histories and Reflections on Community Armed Self-Defense.” He wants readers to not only be safe when using firearms, but to think about engaging in guns in different ways.

“The book was written for leftists who are thinking about taking up guns, so that we don’t perpetuate the same problems that are already in gun culture,” crow said. “It’s not White, male and patriarchal in the sense that it’s always about taking care of the family.”

As with the civil rights movements from the ‘60s, crow knows that this ideological shift will take some time.

“When I first started talking about the use of guns at all, you would have thought we had just killed babies or something,” he said. “And even when I took up guns in New Orleans after Katrina it wasn’t hunky dory. People just wagged their fingers at us.”

However, he said the current civil rights movement may be a much-needed push in that direction. And groups like the John Brown Gun Club could not have come at a better time.

“It’s a major watershed moment. They are now finding a new way where guns don’t become the central importance of community defense, but are a valued part of it,” crow said. “Just like health care, education, and everything else.”

‘Standing with fellow comrades’

Hunter Brown considers himself a history nerd. Fueled by his thirst for knowledge, Hunter grew up researching American history and major events on his own time. One of those formative events was Bleeding Kansas.

“I’m born and raised in Kansas, and so I think John Brown is one of the greatest Americans that ever lived,” Hunter said.

Named for years of bloodshed along the Missouri-Kansas border, Bleeding Kansas was a series of violent confrontations during the Civil War-era. The conflict was a result of two factions vying for control over Kansas’ status as a free state or a slave state.

Abolitionist John Brown became a prominent figure during this time, carrying out raids and attacks with an army of freed slaves and supporters. While regarded as a “terrorist” by some, others, like Hunter, see John as a martyr.

“I’m all about what John stood for and many other abolitionists who gave their lives and were willing to take others for the idea of freedom and equality,” Hunter said.

So when he determined from an inactive Facebook page that the only Kansas chapter of the John Brown Gun Club was defunct, Hunter decided to start his own chapter out of his hometown of Russell.

“Since there is no real hierarchy, there’s nothing to stop me from standing with fellow comrades and starting my own chapter here,” Hunter said.

The group went live in late June and now counts 33 members. They have since co-organized a Black Lives Matter rally with about 75 people in attendance, and organized multiple range days for members to practice using their firearms.

And while they are based out of Russell, the group is open to anyone from Kansas. Although there are members he hasn’t met yet, Hunter is confident that they all share the same basic belief.

“One thing we can agree on is that by being a community and connected to one another, that can keep us safe,” Hunter said. “That is the basis, that all of us are equal, and none of it gets better for any of us until it gets better for all of us. So lean on your neighbor.”

This sentiment is shared hundreds of miles away in Columbia. The mid-Missouri chapter started COMO Mutual Aid, which gets 15-20 requests per week. Requests range from rental assistance to delivering prescriptions.

They also run a mobile soup kitchen during the winter and brake light repair clinics during the warmer seasons. Burhans said several members also volunteer to work with the homeless population.

“People who are doing this kind of work need to be from the community and be in touch with the community,” Burhans said. “That’s really what this whole movement is about is building community.”

Mawa Iqbal is a summer intern at Kansas City PBS.

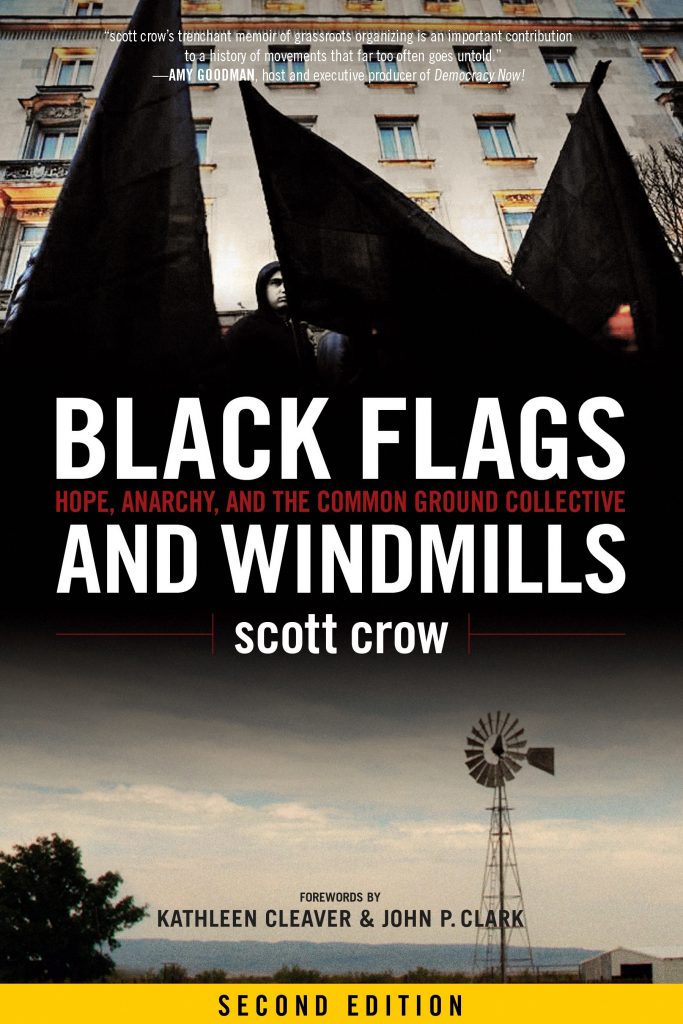

scott crow is an international speaker and author. His first book, Black Flags and Windmills: Hope, Anarchy, and the Common Ground Collective, was included on NPR’s Top Summer Reads of 2015. Black Flags and Windmills has been translated into Spanish, Russian, and Chinese. He is a contributor to the books Grabbing Back: Essays Against the Global Land Grab, Witness to Betrayal, The Black Bloc Papers, and What Lies Beneath: Katrina, Race, and the State of the Nation.