By George Lakey

Waging NonViolence

May 21st, 2020

As activists weary from war, campus killings, a tyrant in the White House and poverty at home started dropping out, Movement for a New Society built a model of sustainability.

“I’m throwin’ in the towel,” he said in a tone of resignation. I’d been away for a while and didn’t expect this. I started to interrupt, but he went right on speaking.

“The shootings, man. Even the FBI admits that bombings of religious groups are increasing. We have a president who wants to be a dictator. Nobody knows what’s coming next. I just can’t handle it.”

We weren’t close, but more than once we’d shared a beer after a political meeting, and when we were on the same picket line we were glad to see each other. Now he tells me he’s dropping out of the movement.

It was the end of the summer in 1970, a few months after the Jackson State and Kent State killings, and he was right about President Nixon wanting to be a dictator. America’s war in Indochina was terrible, along with poverty here at home. Things looked bad.

I couldn’t blame him for burnout, but he represented a growing number of caring activists who hadn’t been able to sustain themselves for the longer run. I understood the stress. I remember someone else reaching for some humor to say what it was like: “If you’re not overwhelmed, you’re not paying attention.”

That was 50 years ago, and now, in the midst of what we’re going through these days, the question comes up again: How do we sustain our activism for the long run? When people drop out, movements miss their hard-won skills, experience and relationships that make alliances stronger. On multiple levels, burn-out costs movements dearly.

Learning together, in a supportive community, would handle anxiety by emphasizing, “It’s not all about you, it’s about us. Together we’ll learn to make a difference.”

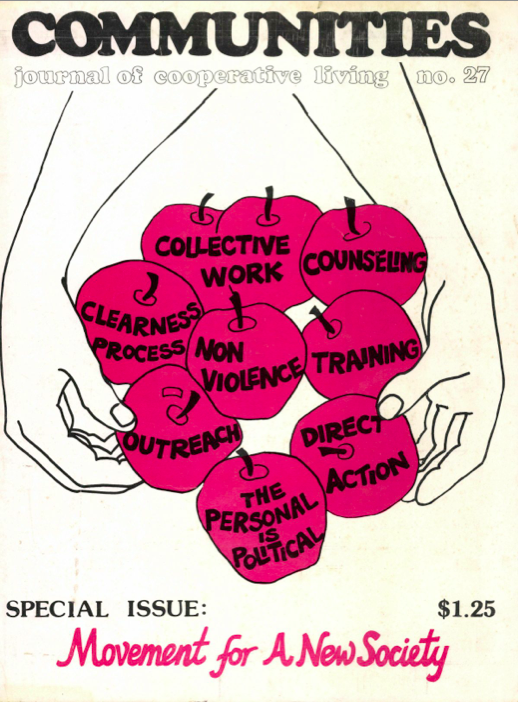

The good news is that the 1970 version of the sustainability problem spurred an informal group eager to find a solution. After a year’s worth of research and development, the Movement for a New Society, or MNS, was born in 1971. MNS became a national cadre organization whose members supported larger movements to make a difference.

A number of elements in the organizational design supported resilience in the members. We also made mistakes, one of which was big enough eventually to end the organization after nearly two decades. Notably, even after dissolution in 1988, many MNS members continued as activists, sharing their skills and experience with subsequent movements.

Using organizational forms that teach members to support each other

While based in London in 1969-70, speaking and training in Europe, I was intrigued by the Dutch activist group Shalom, which built a training center to serve a network of autonomous action groups. When I came back home to the United States, along with the burnout I also found new people coming forward to give activism a try.

I pulled together some veterans of the ‘60s movements along with several different clusters of young activists. The invitation was to explore ingredients for a group that could do radical action and at the same time support the sustainability of the members. We realized that training would be key, because it builds competency and a sense of craft, and therefore reduces overwhelm.

Our first decision was to adopt the proposal of long-time activists George and Lillian Willoughby to put training together with cooperative living, in a center. Learning together, in a supportive community, would handle anxiety by emphasizing over and over, “It’s not all about you, it’s about us. Together we’ll learn to make a difference.”

Another way of experiencing that support is through task collectives (if that’s the premise and the members get the training). Because we could invite task collectives around the country to form a network, do action and — if they chose — live together, we thought the Shalom structure would suit us well. We also expected the Philadelphia base (or “hub” in today’s language) to achieve critical mass, which could then provide training resources that supported everyone in the network.

We found an inexpensive neighborhood in Philadelphia where we could buy and rent large Victorian houses for cooperative living, with 6-10 in a house. Our five collective houses grew rapidly to 10, and then stabilized at about 15.

Expenses, childcare, cooking, cleaning and repairs were shared within each household. Income needs for individuals dropped dramatically. Bringing living expenses down meant most people worked only part-time for income, saving the rest of their time for movement work.

Easily available socializing created a natural context for support, and we imported a peer counseling method that addressed the inevitable issues that come up when individualists try to cooperate.

We planted our training community in a high-turnover Philadelphia middle- and working-class neighborhood which some realtors, unbeknown to us, planned to turn into a slum. Our community organizing succeeded in saving the neighborhood. In fact, two neighborhood institutions that we started are still thriving 50 years later: a food coop and a land trust. Researcher Andrew Cornell presents a lively picture of MNS in his book “Oppose and Propose: Lessons from Movement for a New Society.”

A network of teams, or collectives

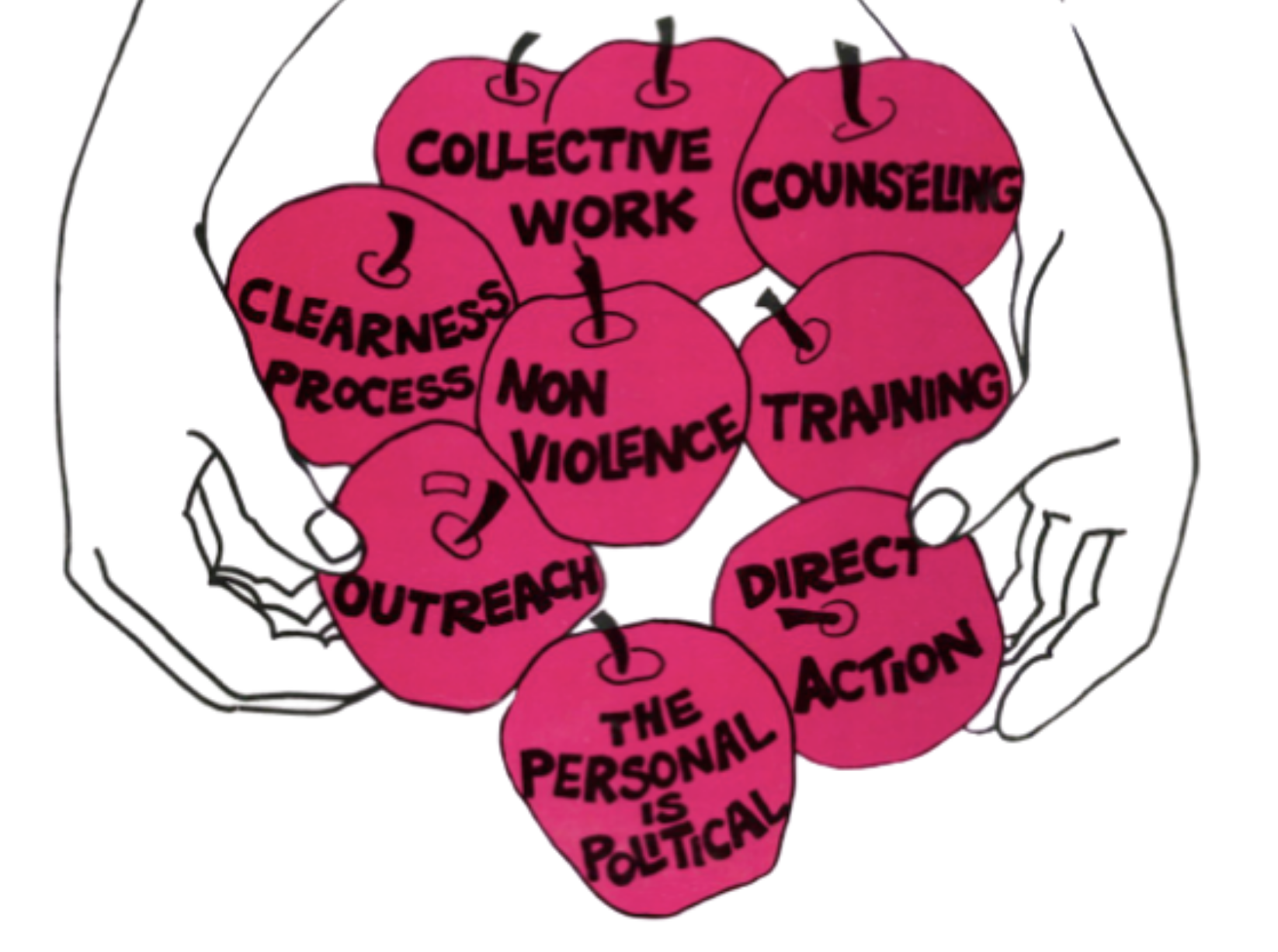

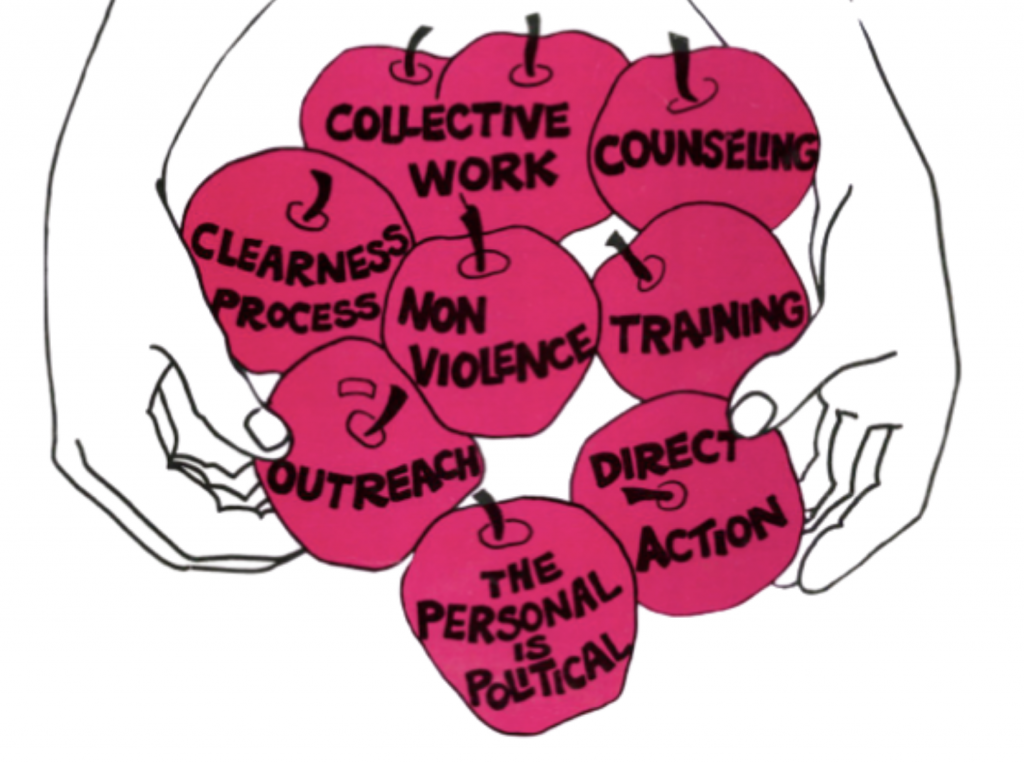

The fundamental national structure of MNS became a horizontal network of collectives. Each collective was a face-to-face group focused on a project, like organizing the direct action blockade campaign that aroused the longshoremen’s union to refuse work in solidarity with the suffering people of Bangladesh. Another collective organized a neighborhood safety program, which put us and our neighbors side by side in dealing with a crime surge. A third did outreach and communication for the national network, while a fourth started and ran New Society Publishers (still going, on its own). There were many others; each collective was autonomous in relation to its own work, once having agreed to the basics of the overall concept of nonviolent revolution.

After the MNS network was established, new collectives applied to join, which involved a dialogue to achieve clarity on the high common denominator that characterized the network. One of the expectations was willingness on the part of a collective’s members to “have each others’ backs” when a collective got over its head. Giving and receiving support was another element in our design for sustaining activists. Inspired by the Wobblies of the early 1900s, MNS created a kind of “power grid” in which members were pledged to come to each others’ aid when a collective called “Crunch!”

The MNS theory of change supported sustainability by giving up a typical activist preoccupation with analyzing what’s wrong. Our alternative was to focus on vision.

The only way a person could become a member of MNS was to be a member of a collective. Non-members interacted with MNS members in many ways, including residing in the cooperative households, joining the co-op, going to the numerous parties, sing-alongs and other social life. Still, the right to a voice in MNS decision-making was reserved to those who were part of a mutual-accountability structure — the collective.

This part of the structural design was key: The organization was accountable to members who were themselves accountable to the people they worked with most intimately. This feature increased reliability, which maximized safety and trust, which in turn reduced anxiety and burn-out.

The reliability that maximized trust also made internal conflict safe for the members, since internal conflict is essential to ensure a robust learning curve. Activists, we believed, are less likely to burn out when they experience themselves as actively learning and growing.

To strengthen the learning we built into MNS the expectation of continual evaluation and feedback. A working collective often invited a facilitator to help them reflect on their work, including their teamwork. Individuals sometimes asked others to meet with them to help them reflect on their personal growth. I used that method when I had a cancer that was expected to kill me; my support group of MNS members assisted me to look honestly at my life and empower myself for healing.

A collaborative learning style

MNS had a slogan: “Most of what we need to know, we have yet to learn.” We found that this helped support serious study, training and also sustainability. Part of burning out can be giving up on ourselves when our performance doesn’t fully meet needs and expectations. Members found that the slogan embedded forgiveness.

In contrast to the individualism of high school and college study, the favored learning style for MNS was collaborative. Members enrolled themselves in one of the Macro-analysis Seminar groupings to study the large forces that influence our chances for success. The Macro-analysis Seminar was mainly initiated by Bill Moyer, who — while on Martin Luther King’s national staff — had seen the importance of the macro level for King, and ways that capacity could be furthered through MNS.

The MNS theory of change supported sustainability by giving up a typical activist preoccupation with analyzing what’s wrong. Our alternative was A/V/S: Analysis, Vision and Strategy. The emphasis on vision put us in line with trainers of Olympic athletes: Clarify and make as real as possible the vision of what winning will look like.

Just as important to Olympians is to develop a strategy for getting there. The seminar emphasized that strategy and vision are as important as analysis if we are to make the degree of change we want.

The Macro-analysis Seminar taught people how to learn in small groups, just as MNS organizers in direct action situations encouraged crowds to form face-to-face affinity groups. There is no substitute for the degree of support that small groups can give. This lesson had been learned by military researchers investigating combat situations: The face-to-face units are the most effective in assisting soldiers to reduce fear and stay with the challenge.

MNS members dissatisfied with the quality of training then available to most activists formed a training collective that studied adult learning, read Paolo Freire, learned from Swedish activists and the civil rights movement, and created experiential methods that improved training.

As a result, training became crucial to MNS’ networking with and influencing the burgeoning movement against nuclear power. When MNS members were locked up in New Hampshire armories along with thousands of anti-nuclear activists in the Clamshell Alliance, they ran many hours of training sessions for the Clamshell’s affinity groups. Training across the country assisted the grassroots anti-nuclear movement to remain grassroots, and win. Even today, Leif Taranta, a young climate organizer, reports that memories of Clamshell make it easier to recruit New Englanders for today’s climate fights.

Oppression/liberation issues

MNS valued liberation from sexism, racism, classism and homophobia, knowing that those burdens and others drag us down and lead to burn-out. Working on those issues, however, can be divisive, and indeed has torn some organizations apart and left individuals adrift.

Knowing that, MNS emphasized solidarity — our fights with each other need to acknowledge that we are, fundamentally, allies. Even while MNS was forming, the women’s movement was accelerating, and we quickly formed men’s support groups to assist the processing of women’s powerful speak-outs and the inevitable gender conflicts in collectives and cooperative living. The expectation that members of the oppressor group, as well as the oppressed group, would form support groups became a support for sustainability.

Our approach to classism was a striking departure from Marxist studies. Even though MNS included a Marxism study group, the work with the larger membership was highly experiential — as we working-class members liked to say, “Down to earth.” As our awareness deepened we noticed that the work on other oppressions was frequently marred by classist patterns. One way this showed up was competition: “My oppression is more important than yours and should get priority attention.” The attempt to pull “oppression rank” sometimes evoked hilarity, when we caught ourselves competing to be at the top of the food chain.

As MNS tried to change we found ourselves held back by our commitment from the outset to consensus decision-making.

To handle the complexity of this dance, MNS largely focused on one area of oppression at a time. In the early ‘70s sexism was the primary work, then as gains were made in that arena, we tackled homophobia with speak-outs, informal confrontations and the essential support groups. After hard work and progress noted, MNS moved on to classism and racism.

The willingness of MNS to say “yes” to conflict, and emphasize both the value of joining and differentiating, supported its members to grow as activists and human beings. By focusing mostly on one oppression at a time, members were able see commonalities and differences in the liberation process, grow both as allies and as people subject to mistreatment, and heal from injuries in a way that supported their personal power and effectiveness as activists.

A sustainability element that didn’t work out well

MNS handled many differences and tried to maintain an internal culture that was conflict-friendly, while at the same time uniting, by framing its organizational mission in a highly rigorous way: Service to people’s movements that contributed to a nonviolent revolution.

Throughout the ‘70s and into the ‘80s, MNS “punched well above its weight.” Circumstances change, however, and organizations need to change as well. As MNS tried to change we found ourselves held back by our commitment from the outset to consensus decision-making. That choice was consistent with trying to give every member a sense of belonging, as we believed that belonging helps to sustain people in the struggle. That structural element, however, prevented making needed changes, since even a tiny minority could block forward motion.

We looked for ways to taste liberation in the collective reality of our work and daily life.

I learned, too late, that a change organization structured so it cannot change itself is a contradiction in terms. As the person who’d catalyzed the creation of MNS, I felt it my responsibility to catalyze its dissolution, and helped the group lay itself down in 1988.

Ever since, I’ve remained proud of many of the experiments we tried. In later organizational contexts I saw many of our design elements working well, delivering strong support for people who might otherwise give way to hopelessness or find themselves stymied by inner conflict. I’m curious now to learn which of the supports for sustainable activism that MNS found valuable will work for organizations facing that question anew.

‘Living the revolution now’

Having large aspirations risks burnout when results turn out to be less than what was hoped for. An incrementalist’s solution is to give up large aspirations. MNS’ solution had two parts, both of which kept us in touch with our aspirational vision. Each of them might be applicable right now.

The first part was to work for achievable steps that help strategically to build the mass movements required to make the needed system change. A new collective wanting to be “cleared into” the MNS network needed to explain how its work would increase the chance of making a revolution. Our theory of change offered examples: nonviolent direct action campaigns that could build movements, alternative institutions that could be proving grounds for revolutionary vision and training for grassroots leadership development.

None of these activities was considered a substitute for the needed revolution, but instead as steps toward its realization. At each step we could declare victory while affirming where the steps lead to: our large aspirations.

The second part of the MNS solution was to “Live the revolution now.” We looked for ways to taste liberation in the collective reality of our work and daily life. Singing in jail, dancing at parties, using our spiritual practices, conflicting and celebrating in our retreats, and loving in liberated relationships gave members the experience of what we expected would one day be common for everyone: living with respect and equality, supported by the institutions of a new society.

I remember a national network meeting at which we gathered to do business after lunch, starting as usual in a circle of singing. Song after song, with rising spirit, and some members dancing and weaving, the agenda waited for over an hour in a usually punctual group, because the circle of radiant faces spontaneously took precedence.

As we reached with each other to touch base with a spirit beyond words, our high aspiration was renewed, as well as the determination to continue taking necessary risks for the revolution to come.

George Lakey has been active in direct action campaigns for over six decades. Recently retired from Swarthmore College, he was first arrested in the civil rights movement and most recently in the climate justice movement. He has facilitated 1,500 workshops on five continents and led activist projects on local, national and international levels. His 10 books and many articles reflect his social research into change on community and societal levels. His newest books are “Viking Economics: How the Scandinavians got it right and how we can, too” (2016) and “How We Win: A Guide to Nonviolent Direct Action Campaigning” (2018.)