By Ted Glick

Future Hope column

June 11th, 2020

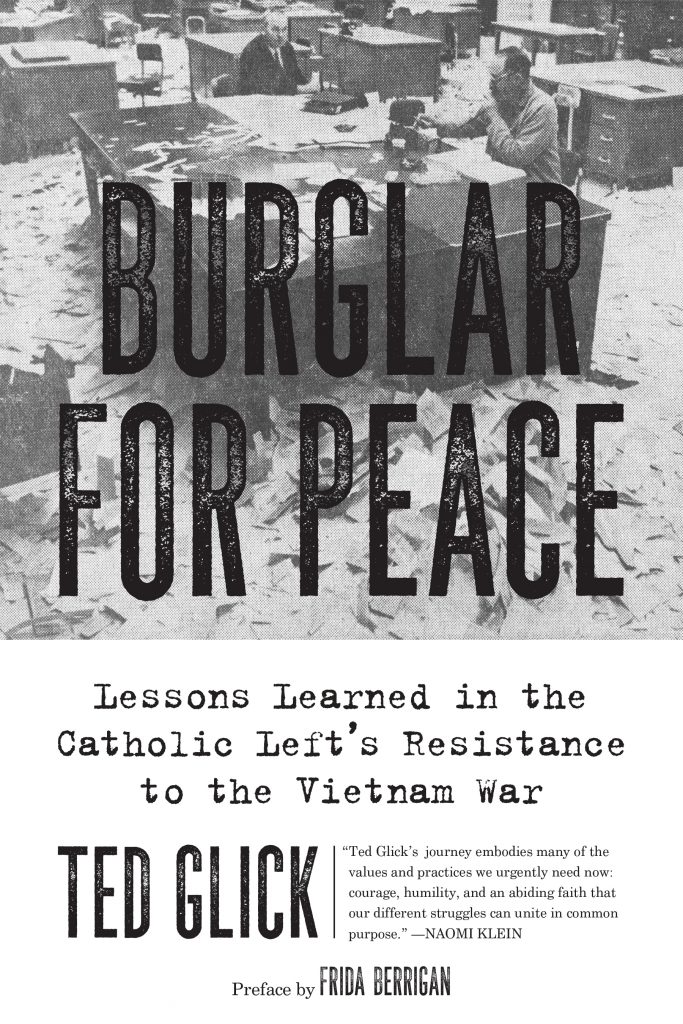

(This is an excerpt from the “Lessons Learned” chapter of my just-published book, “Burglar for Peace: Lessons Learned in the Catholic Left’s Resistance to the Vietnam War,” available at pmpress.org.)

My first years of progressive activism and organizing took place during the presidency of Richard Nixon, who, without a doubt, led one of the most, if not the most, repressive presidential administrations we have experienced in the U.S. in the modern era. It was under Nixon that the Republican Party, with its “southern strategy,” began to move toward becoming the kind of regressive entity that allowed pathological liar, racist, and sexual predator Donald Trump to be elected president in November 2016.

During Nixon’s first term, from 1969 to 1973, he oversaw the use of government agencies to attempt to destroy groups like the Black Panther Party and the Young Lords, including armed attacks by police that resulted in deaths. Newly enacted conspiracy laws were used to indict leaders of the peace movement and other movements. An entirely illegal and clandestine apparatus was created to sabotage the campaigns of his political opponents in the Democratic Party, leading to the midnight break-in at the Watergate Hotel that eventually led to the exposure of this apparatus and Nixon’s forced resignation from office in 1974.

I personally experienced this repressive apparatus primarily as a defendant in the Harrisburg 8/7 trial, the Henry Kissinger kidnapping conspiracy case [a non-existent conspiracy which was dropped by the government after a jury in Harrisburg, Pa. was hung 10-2 for acquittal].

I learned several things during those Nixon years about how to deal with government repression. Unfortunately, given the reality of a Trump/Pence administration, those are very relevant lessons today.

One critical lesson is that there is a disparity in the government treatment of people of color—Black, Latino, First Nation, and Asian—compared with the treatment of people of European descent—white people. The historical realities of military aggression, broken treaties, slavery, Jim Crow segregation, assumed white dominance, and institutionalized racism continue to have their negative, discriminatory impacts.

Among these impacts is a willingness by some police to carelessly shoot and brutalize young black men and other men of color for no justifiable reason, which has given rise to the deeply important Movement for Black Lives.

Another impact is the unequal treatment meted out within the legal system, from police to prosecutors to prison personnel, when it comes to people of color compared to white people. For example, people of color arrested as part of a nonviolent civil disobedience action may be subject to heavier charges or additional hardship while in police custody or behind bars compared to whites.

Those of us of European descent must be conscious of these realities and act accordingly, ready to speak up and challenge unequal, discriminatory, or explicitly white supremacist words and actions wherever they happen. This is also our responsibility when it comes to discriminatory words and actions toward immigrants, LGBTQ people, women, or any other group.

Another lesson about dealing with government repression is that it can’t be allowed to paralyze or divide organizations or movements. This is one of the objectives of an unjust government trying to repress those who challenge its policies and practices. It is a known fact that government infiltrators are trained to look for differences within a group or movement and make efforts to deepen and harden them. That is one of the reasons why we need to be about the development of a movement culture that is respectful and healthy. Such a cultural environment makes it much harder to create divisions.

Much the same is true with regards to agent provocateurs, people who try to get others to engage in violent speech or action targeting police or other government representatives.

Anger against injustice and oppression is not just legitimate; it is necessary to successfully build a movement for real change. But anger needs to be used in a disciplined way. Those who are quick to call cops “pigs” or throw bricks or otherwise display anger negatively are either government agents attempting to discredit the movement or people who need an intervention. They need to be taken aside and spoken with in a direct, to the point, and loving way about the counter-productiveness of what they are doing. Some will keep doing it, but others will change, maybe not right away but over time.

We need to accept that government surveillance, including informants attempting to worm their way in as far and as deep as they can go, is a given if we are serious about challenging the oppressive system and fundamentally changing it, if we are about revolutionary change. We should be on the alert for such people. When legitimate suspicions are aroused, we should carry out the required research and, if it seems necessary, directly confront the person or persons in question.

I did some confronting a couple of years ago during one of the Beyond Extreme Energy weeks of action at the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. On the second or third day, a new person who, as far as I knew then, none of us organizing the action knew in any way showed up at one of our semi-public meetings. There was something about him, an individualistic, very assertive way of speaking, that raised my antenna. Over lunch I took him aside and asked him in as nice but as direct a way as I could how he had heard about our action and if he knew of or had worked with any of the groups that were part of it. It turned out that he had worked with a couple of us, and when I spoke to them afterward they confirmed that he was okay, even though they understood, given the way he spoke, why I might have been suspicious.

This person took some offense to my questioning him, and he left the meeting, but, to his credit, he did return later that week. I apologized to him when I saw him, and he said it was okay, he understood why I had done it.

There are other affirmative steps we can take to prevent government disruption of our actions. For example, if we are organizing a nonviolent direct action that includes the element of surprise, we need to take whatever steps are necessary, like using encrypted email and other secure forms of communication and consciously limiting what is said or written beforehand to what is absolutely necessary.

Ultimately, what I have learned is that government repression can have a disruptive impact on our work, but we can turn a negative into a positive. The extent to which we can creatively, intelligently, and fearlessly demonstrate the truth of what we are about when responding to what they are doing to us is the extent to which will we strengthen and build our movement.

Ted Glick is the author of the just published Burglar for Peace: Lessons Learned in the Catholic Left’s Resistance to the Vietnam War. Past writings and other information can be found at https://tedglick.com, and he can be followed on Twitter at https://twitter.com/jtglick.

Ted Glick is the author of the forthcoming Burglar for Peace: Lessons Learned in Catholic Left Resistance to the Vietnam War. Past writings and other information can be found at https://tedglick.com, and he can be followed on Twitter at https://twitter.com/jtglick.