By Stephen R. Shalom

New Politics

October 9, 2022

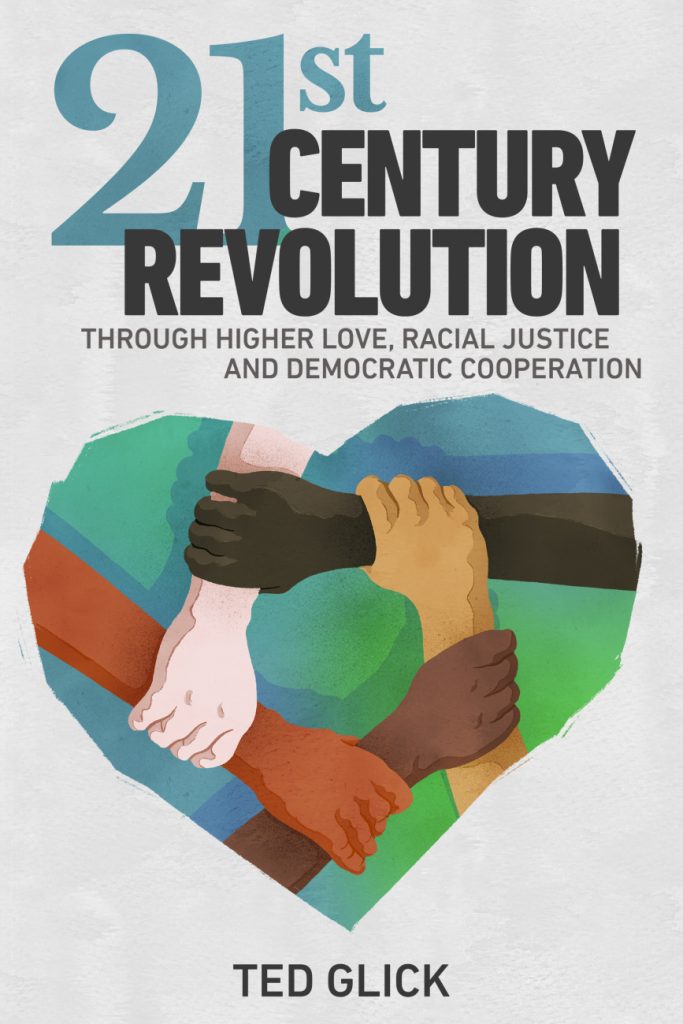

21st Century Revolution: through higher love, racial justice and democratic cooperation, Ted Glick, Bloomfield, NJ: Future Hope Publications, 2021, 114 pp. $10, https://tedglick.com/2021/09/12/21st-century-revolution/.

Ted Glick has been a champion of radical social change for over five decades, tirelessly working for peace, justice, independent politics, and climate survival. It this short book, he shares some of the conclusions he has drawn from this lifetime of activist experience.

Two of the book’s five chapters deal with spiritual matters, which may well put off many readers, but he makes a compelling case that these are concerns that the left ignores at its peril. He is well aware of the obscurantist and reactionary role that organized religion has often played in human affairs, but he argues that this is not the full story. While religion has frequently served to divert people from the need to fight injustice, it has sometimes helped to propel freedom struggles. He quotes the Protestant theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who was killed in a Nazi concentration camp after joining the anti-Hitler resistance: “It is not the beyond that we are concerned with, but with this world.” And “We are not to simply bandage the wounds of victims beneath the wheels of injustice, we are to drive a spoke into the wheel itself.”

Glick reminds us that hard-headed historical materialist Frederick Engels considered that Thomas Muntzer, the leader of the 16th century German peasant wars, was both a religious and a political revolutionary. The kingdom of God that Muntzer demanded be immediately established on Earth was to have no class differences, with all work and property shared in common. Likewise Karl Kautsky, a leading theoretician of social democracy, wrote of the “outspoken proletarian character” of early Christianity, aiming for “communist organization.” Kautsky, however, criticized early Christian support for an equal distribution of wealth, arguing that socialists had to instead push the concentration of wealth to the highest point and then turn it into a state monopoly – not exactly an inspiring vision, remarks Glick, or one likely to lead to the classless and democratic societies found among early Christian communities.

The Bolsheviks’ official position prohibited discrimination against anyone on the basis of religious beliefs and did not require party members to be atheists. But Lenin’s critique of religion went beyond condemning the reactionary role played by the clergy of the Orthodox Church. “Our morality,” he said, “is entirely subordinated to the interests of the proletariat’s class struggle.” Lenin’s dismissal of religion even extended to the non-theistic humanism promoted by revolution-supporter Maxim Gorky. Under Stalin and under Mao in China the ruling parties were actively atheist.

Again, Glick does not soft-pedal the way that organized religion has supported the unjust and oppressive status quo. But he describes how small groups (and sometimes even large ones) have found inspiration from religion to speak truth to power, sometimes doing so in response to socialist criticisms. In Belgium, Italy, and France, there were movements of many thousands within the Catholic Church from the 1920s to the 1950s that sided with oppressed working people. The Cuban revolution, says Glick, had a more tolerant view of religion than did the Soviet Union or China, helping to inspire Liberation theology in Latin America and beyond. However, the fact that the Cuban Communist Party – the country’s only legal party – didn’t allow religious believers to join until 1991 seems much more problematic than Glick allows, and the government’s authoritarianism certainly contradicts our notions of democracy.

Forty years ago I met radical nuns in the Philippines who worked with the urban poor. When I asked them about birth control, they told me that while the Pope disapproved of it, they did not. Today we have a Pope who has been influenced by liberation theology. Nevertheless Glick acknowledges that the Catholic Church is still a thoroughly patriarchal institution.

Glick ends his first chapter concluding that the path forward for those who seek social change “must be wide enough to allow secular and spiritually-grounded revolutionaries to walk it together.” He notes that in his experience many groups have fallen apart because of the failure to establish collaborative, respectful, and democratic practice. This, more than the correct line, is critical if groups are going to last.

Glick’s second chapter is titled “Does God Exist? Does It Matter?” I approached this chapter with a great deal of skepticism, but, admirably, Glick too is skeptical of his own views, as they evolved over time. Although I was unpersuaded by many of his arguments over the course of the chapter, his conclusion – quoting Einstein – is compelling: “A positive aspiration and effort for an ethical-moral configuration of our common life is of overriding importance. Here no science can save us.”

Chapter three addresses capitalist culture. Marx, Glick argues, had a blind spot regarding the importance of personal change for social change. We need to challenge capitalist culture in our own lives and organizations if we hope to build movements that can achieve a just world. Glick discusses hunter-gatherer societies and their non-acquisitiveness as something to be emulated, but this strikes me as overly romanticizing the primitive, as Glick himself afterwards somewhat concedes. But there is no disagreeing with him when he urges left organizations to stress diversity and cooperation and to create a culture that encourages honest discussions of real differences of opinion. He urges consensus seeking, but without requiring consensus at all times, which can prove undemocratic. One technique he recommends for promoting participation is using breakout groups with reporting back. I think more work needs to be done on developing these participatory methods, because in my experience report-backs rarely result in actionable decisions.

In chapter four, Glick looks at the U.S. class structure and what this means for our social change organizing. In place of a simplistic view that divides the country into two classes, he identifies seven general class groupings in U.S. society. Each one of these experiences a different life situation and has a different propensity to support a left movement. The suffering of the barely-surviving working class makes them more open to the left, and no left can fail to address their needs. The low-income working class on the other hand is the most numerous group and their support is essential for any successful radical change. The moderate to middle-income working class is often quite conservative and will require serious dialogue and even confrontation over issues of race, sex, and gender before they can be won over to the revolution. The professional and managerial middle class will include a minority who are progressives, but we have to be careful not to let their elitism undermine left efforts.

In the final chapter, Glick puts forward a strategy for a 21st century revolution, a strategy that he says already enjoys quite a lot of agreement on the left. We need a broad-based popular alliance, a movement of movements. These movements need to be empathetic, use comradely rhetoric, and devote more attention to inter-movement diplomacy. They need deep working-class roots. Redistribution and the climate need to be central demands. Organizing needs to be “dialogic,” that is, listening to people, not just leading them. He calls for a flexible and tactical approach toward election campaigns, sometimes running independent left campaigns, sometimes supporting progressive Democrats or fusion candidates. It is important, he says, to push for reform of undemocratic electoral laws. And he emphasizes the critical role of direct action.

Glick argues that the movement of movements must also be internationalist, but his discussion here is far too brief. What does internationalist mean? The left is currently very divided over whether internationalism means (a) opposing U.S. imperialism everywhere and supporting all enemies of U.S. imperialism, or (b) opposing all imperialisms anywhere and expressing solidarity with all victims of imperialism.

Ted Glick believes that we can achieve a better world, one without class oppression, racial injustice, or patriarchy, one inspired by spiritual values that have been part of our species for millennia. The path forward is not easy, but one statistic Glick cites provides reason for optimism: by one count there are some 1-2 million groups worldwide working toward environmental sustainability and social justice. This hopeful book urges us to use this potential to achieve a 21st century revolution.