By Mickey Z.

World News Trust

May 14th, 2020

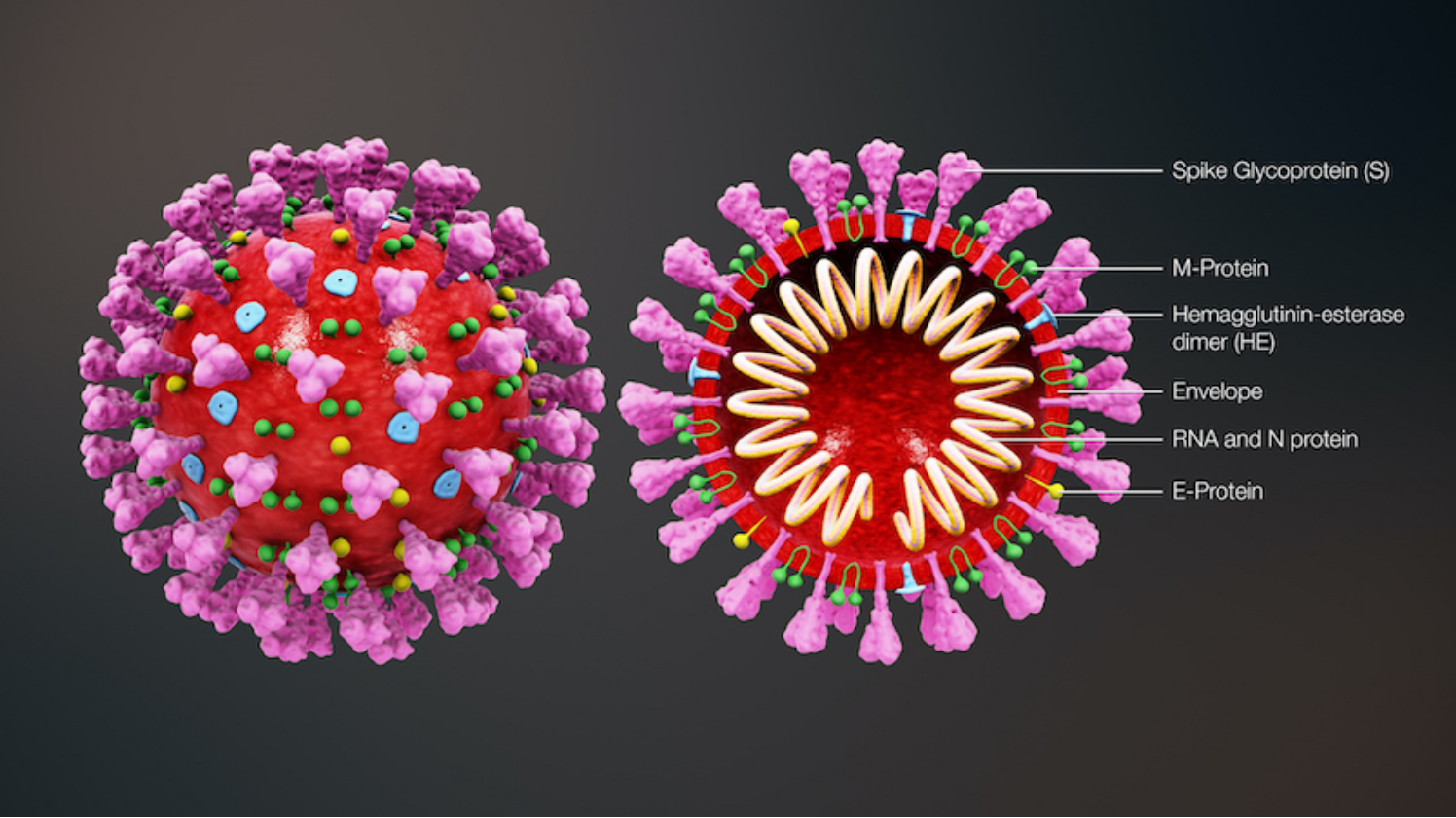

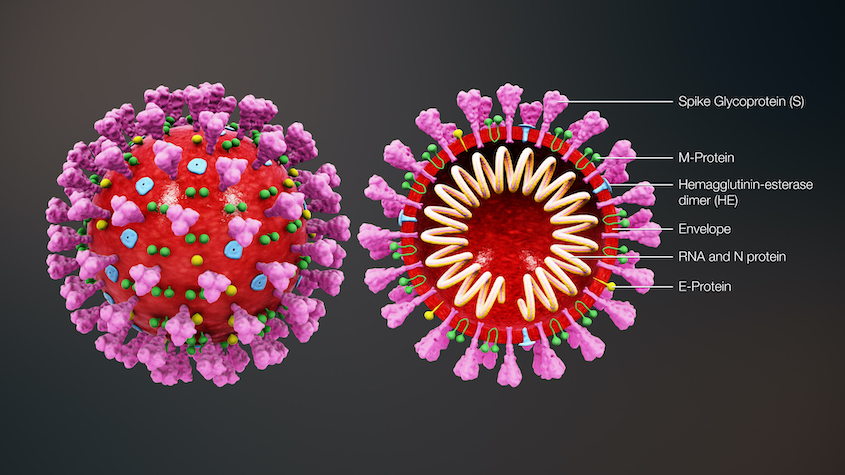

Coronavirus structure. Credit: https://www.scientificanimations.com / CC BY-SA

“It felt like a global tidal wave of human sorrow”

Mickey Z. — World News Trust

May 14, 2020

“At my lowest points, the unsettling realization came to me that given the ferocity and rapidity of change with this virus, a further plunge could mean that I might not survive. Indeed, I felt so close to total suffocation that there seemed little room for further decline. I was determined to fight my way through this, but at the same time, I calmly prepared myself mentally for any eventuality.”

These are the words of my friend, Gregory Elich. They’re not uncommon during this pandemic but I believe his story must be shared within the current climate of uncertainty, misinformation, and division. My goal is not to “set the record straight.” Rather, Greg agreed to this interview because we both saw value in reminding folks of the harsh human realities that exist beyond the headlines, debates, and confusion.

This interview is about one person but his harrowing tale encapsulates much of what’s still going on across the globe. Like Greg, I live alone and I often ponder the logistics of a simple question: What happens if I get sick during the lockdown?

Questions like this highlight what I talked about in a recent article, e.g. the importance of focusing on what is within our control. Therefore, no matter where we stand on the ideological spectrum, we must never forget our shared humanity. Beneath the partisan politics, conflicting theories, and medical contradictions are vulnerable human beings trying to survive — emotionally, financially, and physically. I’m very grateful Greg got through this and has agreed to tell us a little about it.

For the record, I met Greg in 2004 when we were both featured speakers at a large political event in Santa Cruz, California. In the ensuing years, we’ve stayed in touch, wrote blurbs for each other’s books, and developed a strong friendship. I reached out to him via e-mail in early May to do this interview. It went a little something like this:

Mickey Z.: When did you first experience COVID-19 symptoms?

Gregory Elich: I became infected in early March, at a time when it was nearly impossible to get tested. My state, Ohio, followed CDC guidelines to determine where to direct limited testing capacity. Initially, testing was restricted to those who had recently been abroad or to those who had contact with someone who had tested positive for COVID-19. Since virtually no one could get tested, there was practically no way one could have contact with anyone testing positive. Later on, the guidance was adjusted so that testing was limited to healthcare workers and hospitalized people showing symptoms.

Under the circumstances, all that could be done was to test me for normal type A or type B flu. Had either test produced a positive result, it would have ruled out COVID-19. The results of those tests were negative.

MZ: Do you feel confident you would’ve tested positive for COVID-19?

GE: I believe so. This virus is like nothing I’ve ever experienced, and my symptoms closely matched those that have been reported. Naturally, since it was not possible to get tested, I am not included in the statistics. At that time I was reading about so many others who, like me, were repeatedly stymied in their efforts to get tested, regardless of how sick they were. I suspect there are millions of people who were in the same situation.

MZ: It’s interesting that the final count will never truly be known and how this fact will be used by a wide range of groups as evidence for whatever their angle on the pandemic may be. How would you respond to someone who wouldn’t want to list you among the COVID-infected or would doubt such status?

GE: Obviously, I cannot prove it, unless someday I can get tested for antibodies. The reader can judge from the description of my experience whether or not to believe that I was infected with COVID-19. However, my case is irrelevant to the larger argument about the overall impact of the virus. My experience does not alter the fact that a great many people who were seriously ill were unable to get tested. Also, a great many people who died were not counted, since the dead aren’t typically tested for COVID-19. Because the virus interferes with the passage of oxygen to the bloodstream, it can wreak havoc in a variety of organs. In particular, cardiac arrest is not uncommon. COVID-19 can bring death in a variety of ways. It concerns me that policy decisions are being made based on flawed statistics that undercount the true extent of the pandemic in this country.

MZ: Back to you and the illness, how did it manifest for you?

GE: I’ve never been so sick in my life. The experience people have with this virus ranges from being asymptomatic on one end, to life-threatening at the other. I’d say mine fell right in the middle and would be labeled as mild or moderate. The terms are relative, of course, as there was nothing in this ordeal that seemed quite so gentle to me.

The first two days, my only symptom was an intense headache beyond anything I had ever experienced before. On the third day, the dry coughing began. Nonstop coughing fits would come and go in cycles, usually lasting around two to three hours, interspersed with approximately equally long periods where the coughing was sporadic.

On the fourth day, I started feeling short of breath. As the days went on, the dry coughing worsened, as did the shortness of breath. Physically, I felt completely wiped out, and I spent almost all of my time lying down. I had to put an increasing amount of effort into each breath, which was wearing.

From the second week onward, the coughing fits intensified, with the longest one lasting around 35 consecutive hours.

Because I have sleep apnea, I have a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine. On several days, I used my CPAP machine during the daytime so that I wouldn’t have to work as hard to get enough oxygen.

While the CPAP helped to reduce the amount of effort I had to put into breathing, it did not change the fact that I was struggling. It was impossible to take a deep or even a moderate breath. My lungs felt constricted, and the sensation I had was that only the top third of my lungs were taking in air. That probably wasn’t literally the case, but the overall capacity was certainly limited.

MZ: Would the sleep apnea be considered an underlying risk for something like COVID-19?

GE: There is no evidence that sleep apnea is a risk factor. I think it is important to point out, though, that the exhaust from a CPAP mask is spectacularly effective at spreading the virus. So if anyone becomes infected by COVID-19 who uses a CPAP and lives with others, it is essential to sleep in a separate room.

MZ: Did the symptoms fluctuate?

GE: That was the oddest thing about the sickness. My condition was like a roller coaster. I could never tell if I was improving or not. There were two periods where I had three straight days where I seemed to be improving, and I thought I was on my way to recovery. In both cases, within the span of one or two hours, my condition plunged so rapidly and so steeply that it was alarming. I suddenly found myself feeling on the verge of suffocating, and I was gasping for air. All I could do was focus on putting all of my energy into each intake of air, inadequate though it was. The experience is worse than one could imagine, and the thought occurred to me that this would be a horrible way to die. During those periods, the CPAP was of no use, as trying to force air into my lungs when the capacity just wasn’t there only magnified the feeling of suffocation.

I read an article by a doctor who described the fluctuation perfectly. He said that when patients with COVID-19 crash, they crash very quickly and crash very hard. “Each patient is a ticking time-bomb,” he added, “and then — suddenly — they are gasping for air with plummeting oxygen levels and a plummeting blood pressure.”

MZ: Did you consider going to the hospital?

GE: The hospitals were overwhelmed. Respirators and ventilators were in short supply, as were personal protective equipment (PPE) for medical personnel. State officials were urging people not to go to the emergency rooms, lest they infect others. State officials were emphasizing that what little equipment and PPE was available needed to be reserved for those patients in the most severe condition. They advised that infected people should work through their doctors to determine when or if hospitalization was needed. In this situation, one has to consider the broader social need. Had I gone on my own to the hospital, I may have deprived someone who was in greater need, with perhaps lethal consequences for that person.

MZ: How did that play out for you?

GE: I had two tele-appointments with my doctor. I asked my doctor what sign I should watch for that should trigger me to call about arranging a trip to the hospital. He told me the key to judge by would be if I was sitting in a chair and by standing up, I was so out of breath I couldn’t take another step. That would be the way of determining if I needed a respirator or ventilator. As he pointed out, unless one needs a respirator or ventilator, there is no treatment for the virus that a hospital can offer.

MZ: This must have been hard to accept knowing how volatile your symptoms were.

GE: At my lowest points, the unsettling realization came to me that given the ferocity and rapidity of change with this virus, a further plunge could mean that I might not survive. Indeed, I felt so close to total suffocation that there seemed little room for further decline. There was no way to know what the next hour would bring. I was determined to fight my way through this, but at the same time, I calmly prepared myself mentally for any eventuality.

MZ: Was the doctor able to offer any long-distance help?

GE: At my first tele-appointment, my doctor prescribed an inhaler, codeine cough medicine, and an antibiotic to ward off pneumonia. On the second tele-appointment, I was prescribed more codeine cough medicine and prednisone to reduce inflammation in the lungs. These helped, although the cough medicine proved ineffective during my worse coughing fits.

MZ: Was the medicine delivered to you or were there times you could venture out to the pharmacy?

GE: I go to a small family-owned drug store, so it was possible to make special arrangements. I certainly did not want to infect anyone there, so I waited until I was in one of my milder cycles. Then I called the pharmacy and arranged a set time to show up at their parking lot. Once there, I remained about 100 feet from the door. At the prearranged time, one of the pharmacists came out and set my bag on the ground. Once she was back inside, I went and picked it up. On my way home, I mailed them a check.

MZ: We’ve all heard about the 14-day incubation period. How long were you feeling ill?

GE: I was sick for around six weeks. It lasted so long that it was difficult for me to imagine being well again. But I did recover, and now I am just so happy to be alive and healthy!

MZ: It’s so jolting to have a specific face put on something as abstract as a “pandemic.” I hope that’s what we’ve accomplished here, in a way. Before we wrap up, is there anything else you feel compelled to share or say about your experience in particular or this entire crisis, in general?

GE: I am grateful to my cousin and several friends who phoned me and/or e-mailed me on a daily or near-daily basis. Their support substantially raised my spirits and made it much easier to cope.

My experience was nothing compared to that of many others. I can’t imagine what it must be like for those who need to go on a respirator or ventilator.

Amid my sickness, my sleep doctor sent out a mass e-mail, evidently to all of his patients. His message included a photo of his wife and a note that she has been on a ventilator for one week with no sign of improvement. He asked everyone to pray for her. I could imagine the anguish and desperation that drove him to send that e-mail. Looking at his wife’s photo, she was so young. I couldn’t stop crying, thinking of what my sleep doctor was going through emotionally and what his wife was going through physically.

It may sound odd, but during my illness, I felt directly connected to every human being across the world who was struggling with COVID-19. That feeling was most intense when I wasn’t entirely sure what my fate would be, but it continues to this day. The virus has brought so much death, suffering, and struggle. It felt like a global tidal wave of human sorrow.

As far as my general feeling about the entire crisis, that can best be summed up by simply stating that human life should come first.

MZ: After such an experience — one that could be accurately described as near-death — do you feel any palpable changes in your daily mindset or perspective?

GE: I’m not sure I’d describe it as a near-death experience, in that I never reached the point where I needed a respirator or ventilator. However, had there been a further decline at a crucial moment, I think I would have been at the edge.

At any one moment, there was no way I could predict which direction I would go, so it was close enough to set me thinking.

What surprised me was being able to calmly face the possibility of death. Aside from that, striving for achievement seemed to lose importance, and the experience only reinforced my belief in the importance of treating others with kindness and respect. I would also add that the support I received from my cousin and friends only reemphasized that in life all we really have that matters is each other.

Actually, I am still sorting through my feelings and this may take some time to fully work through.

***

Gregory Elich is a Korea Policy Institute associate and on the Board of Directors of the Jasenovac Research Institute. He is also a member of the Solidarity Committee for Democracy and Peace in Korea. His website is https://gregoryelich.org Follow him on Twitter at @GregoryElich or @GElich_music

Mickey Z. can be found on Instagram here. He is also the founder of Helping Homeless Women – NYC, offering direct relief to women on the streets of New York City. To help him grow this project, CLICK HERE and make a donation right now. And please spread the word!

Mickey Z. is the founder of Helping Homeless Women – NYC, offering direct relief to women on the streets of New York City — before, during, and after the pandemic lockdown. To help him grow this project, CLICK HERE and make a donation right now. And please spread the word!

Back to Mickey Z’s Author Page