By Ted Glick

Originally posted on Future Hope

April 6th, 2020

“The

truth is that nothing is less sensational than pestilence, and by

reason of their very duration great misfortunes are monotonous. In

the memories of those who lived through them, the grim days of plague

do not stand out like vivid flames, ravenous and inextinguishable,

beaconing a troubled sky, but rather like the slow, deliberate

progress of some monstrous thing crushing all upon its path.”

-Albert Camus, The Plague, p. 179

I’ve read Camus’ classic novel, The Plague, three times, the third time just a couple of days ago, and each time the experience deepened my commitment to taking action for a better world. The main characters in the fictional book, all men, some from the beginning and some later, all throw themselves into the desperate, difficult and emotionally draining fight to prevent a hideous and deadly plague that erupts in the town of Oran, population 200,000 in North Africa, from overwhelming it. As they do so, Camus explores how, through their thoughts, their journal entries and their conversations, they try to handle the existential immensity and uncertainty of what they are experiencing.

There are a number of essentially surface differences between Camus’ Plague and the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. His is concentrated in one town; it is more deadly than, so far at least, it appears COVID-19 will be; his takes place right after World War II, over 70 years ago; and, as mentioned above, all of the main characters are men.

From everything I’ve observed via the news, there are an awful lot of women—nurses, doctors, epidemiologists, media spokespeople, some political leaders—who are major characters in the real-life plague the world is contending with now. I’m glad that’s the case. Women playing hands-on and leadership roles in just about anything improves the chances for better outcomes.

It was not a major theme of Camus, but he did address the issue of price gouging, something which has begun to make the news today in relationship to the exorbitant raising of prices for essential health equipment such as masks and hand sanitizer, and even toilet paper. In the fictional Oran, “Profiteers were purveying at enormous prices essential foodstuffs not available in the shops. The result was that poor families were in great straits, while the rich went short of practically nothing. Thus, whereas plague by its impartial ministrations should have promoted equality among our townsfolk, it now had the opposite effect.” p. 237

It has been striking that those part of the world’s power elite or famous people have come down with COVID-19. Without a doubt, that explains why those like Trump, who tried to wish it away until it became ridiculous to keep doing so, finally had to take it seriously. But it is also true that the lowest-income people, those whose health is not as good, who live in crowded apartment buildings, who have lost their jobs or who have little in savings to fall back on, or those incarcerated, will certainly end up disproportionately impacted by the virus.

It’s like climate disruption. Those hurt the most are those with the least resources to survive storms or droughts or floods, but everyone, of whatever class, race or gender, are at risk of major personal impacts sooner or later.

The narrator of the book is Doctor Bernard Rieux, who is portrayed as the primary medical person doing all he can at great sacrifice to help the victims of plague, rarely with positive results until the very end. At the end, as the town is finally reopened for travel to and from it after nine months of isolation, the townspeople are portrayed as wildly and exuberantly celebrating. Camus doesn’t allow his main protagonist to do the same but, instead, to make a social observation based on experience: “he wished to behave like all those others around him, who believed, or made believe, that plague can come and go without changing anything in men’s hearts.” p. 295

What will come of today’s pandemic? Camus’ implication is that an experience as searing and socially disturbing as a plague has very real impacts, some negative, as in a hardening of hearts due to loss of loved ones or fear of the future, and some positive, as we have seen with this pandemic as far as heroes stepping forward, particularly health care workers, modeling a willingness to risk serious illness or death for others.

But as I have seen numerous such workers say when interviewed, they are also just doing their job. Camus references this. At a point in the Oran plague where the growth of the number of plague victims was straining the town government’s ability to keep up with all that had to be done, several men voluntarily stepped forward:

“Those who enrolled in the ‘sanitary squads,’ as they were called, had, indeed, no such great merit in doing as they did, since they knew it was the only thing to do, and the unthinkable thing would then have been not to have brought themselves to do it. These groups enabled our townsfolk to come to grips with the disease and convinced them that, now that plague was among us, it was up to them to do whatever could be done to fight it. Since plague became in this way some men’s duty, it revealed itself as what it really was, that is, the concern of all.” p. 132

Organizing to change something that is wrong or unjust is like this. At first, a small number of people, maybe even just one, need to step forward and publicly say, “This is wrong, and it must be changed,” and begin taking action. If those actions are carried out in a clear and welcoming way, others also will come forward, and over time, sometimes very quickly, a movement big enough to make change will emerge. This is what happened in Oran due to the initiative of a handful at a needed time. It’s a life lesson.

What’s the big takeaway from The Plague? It’s this: “What’s true of all the evils in the world is true of plague as well. It helps men to rise above themselves.” p. 125 And again, on the final page: “what we learn in times of pestilence is that there are more things to admire in people than to despise.” p. 308

Beginning with clueless Trump, there are certainly plenty of people whose actions during this pandemic are despicable. But they are vastly outnumbered by those who, during this difficult time, are performing admirably, some heroically.

In the meantime, let us all do what we can to help as many as possible survive this pandemic, this plague, and then let’s just keep going afterwards to bring into being a world where plagues of environmental devastation, hunger, war, and systemic injustice are finally defeated.

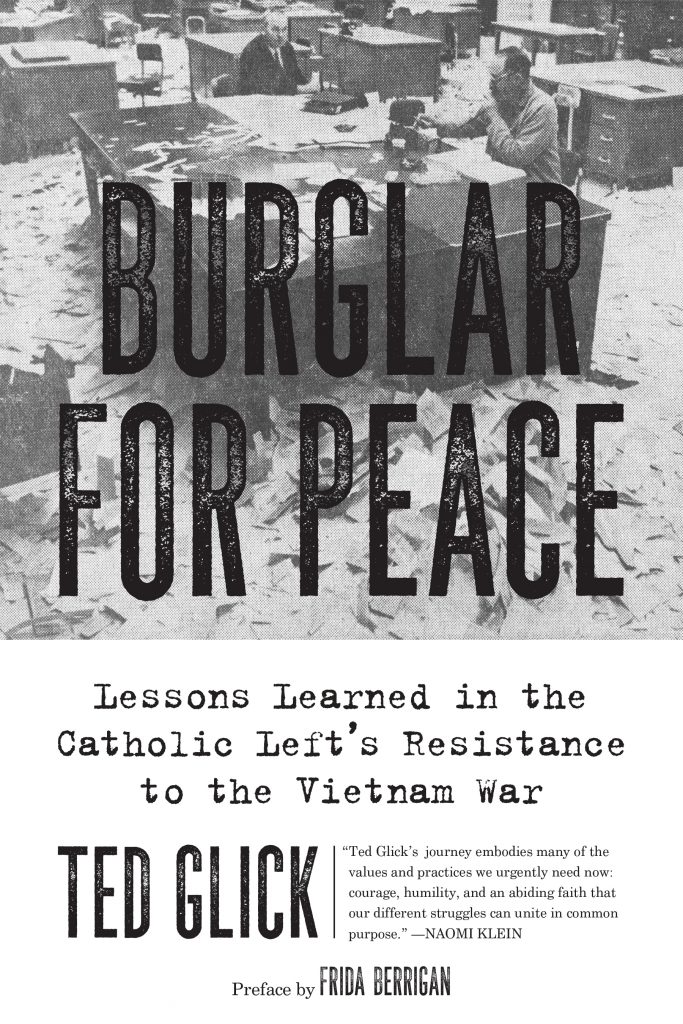

Ted Glick is the author of the forthcoming Burglar for Peace: Lessons Learned in Catholic Left Resistance to the Vietnam War. Past writings and other information can be found at https://tedglick.com, and he can be followed on Twitter at https://twitter.com/jtglick.