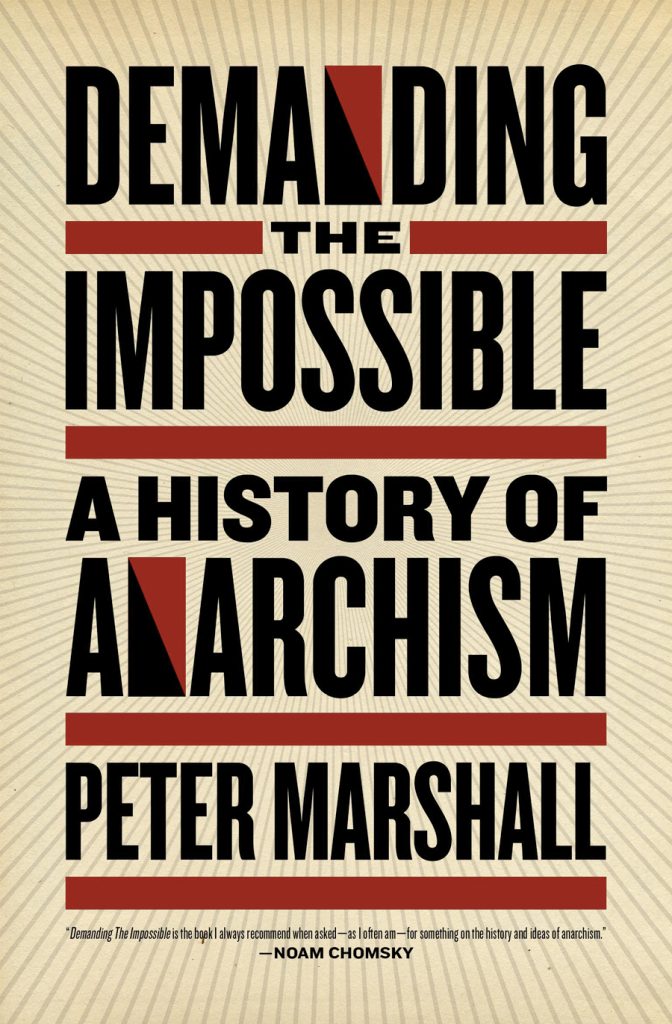

By Peter Marshall

March 25th, 2020

As always we have the choice to fight or flee, to look after ourselves or others, to be anxious and nervous or stay steady and firm. As the history of Thucydides (when plague hit Athens) and as La Peste of Albert Camus (describing the plague in Oran, Algeria) point out, people react to a crisis differently. Some want to leave, some just think of themselves and their immediate family, some want to indulge in pleasure, while others want to help, show solidarity and practice mutual aid. Some flee and avoid, some fight and struggle.

Now is the time to be creative, kind and stoic – stoic in the best sense of accepting suffering and pain as an inevitable part of life.

According to Kropotkin, Zeno of Citium (Cyprus) was ‘the best exponent of Anarchist philosophy in ancient Greece’. I would agree. This 3rd-century BC philosopher was probably the first philosophical anarchist in the Western Tradition. Like social anarchists today, he was against government and advocated a cosmopolitanism which meant working with others and strangers and treating them fairly. He believed we should follow Nature rather than man-made laws.

He was also the founder of Stoicism, that is to say, a philosophy which recognises that humans are all social beings. They should not solely be influenced by a desire for pleasure or a fear of pain. The way to happiness (eudaimonia) is to accept each moment as it comes.

We should enjoy each day to the full (carpe diem) while being ready to accept illness and death. Medieval scholars would often have a human skull – a momenti mori (‘remember that you must die’) – to remind them of the fact that life is short and that death is inevitable. The followers of Tantra amongst the Indian holy men (sadhus) sometimes meditate while sitting on human skulls to remind themselves that all things die. Death is the basis of life as night follows day; you can’t have one without the other, any more than you can have pleasure without pain The whole of Nature shows life is based on death and ends in death. All beings and things are impermanent. People long for certainty and live in a sea of doubt; they wish for eternity but on this earth all is changing.

As Samuel Beckett once wrote in a bleak assessment of humans and the human condition: ‘They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more.’

This is not necessarily morbid. It is a just recognition of the reality of things, of life itself, of things how they are.

I am sure that the present virus and its consequences will make us rethink corporate globalisation; international capitalism, in which the few rich grow richer and the many poor become poorer; the nature of capital and private property driven by profit and the exploitation of labour; the irrelevance and perniciousness of governments and nation states. The present and world-wide outbreak of corona virus will no doubt make us question the rearing and killing of animals as well eating dead flesh. It is not only cruel but a misuse of land (it takes seven times more land to produce one pound of meat protein than one pound of vegetable protein). The sea, like the land, is a common ecosystem and for all humans (who only live on about a third of the earth’s crust) and other animals (including fish) to enjoy.

We can do this by ourselves and for ourselves and for Nature as whole. We don’t need nation states, governments and police and armies to tell us what to do. We can act, think and do it ourselves. We can find what is essential and what is unnecessary, what is really satisfying. We can work out the minimum amount of work necessary to feed, clothe and shelter us, work which truly fulfills our nature, and what are drudgery and a waste of time. We can see what we need and what might be a superfluous luxury. We can consume less and live more. We can change apparent negatives into positives, as I was once told by a Tibetan Buddhist monk in exile in flat plains of India. So we can see the present crisis, however apparently dire, as an opportunity and challenge to change our impossible way of life.

Nothing will ever be the same, that’s for sure.

This is just what one village, on the south coast of England where I live, is doing. The community has arranged voluntary co-ordinators in each road who will help citizens with things such as: picking up shopping; collecting medicines and prescriptions; getting in urgent supplies; having a chat on the phone. There is a daily community news sheet which you can get online. I am sure something similar is happening all over the world. It is called mutual aid.

Peter Marshall is a philosopher, historian, biographer, travel writer and poet. He has written fifteen highly acclaimed books which are being translated into fourteen different languages. His circumnavigation of Africa was made into a 6-part TV series and his voyage around Ireland into a BBC Radio series. He has written articles and reviews for many national newspapers and journals.