March 16th, 2020

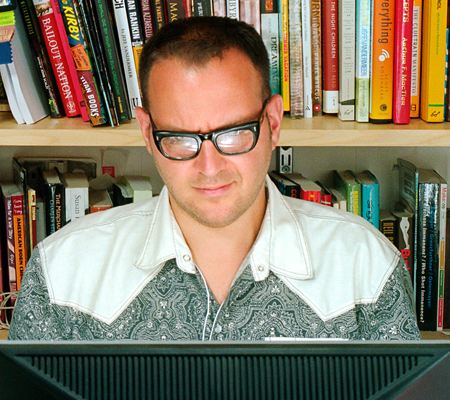

By Cory Doctorow

The thing is, I’ve been here before.

I’ve written any number of apocalypses, so many that I sometimes get

branded a “dystopian” by critics and online audiences and catalogers.

I’m not a dystopian, though.

Here’s the thing: assuming that things will break down does not make you

a dystopian. It makes you a realist. Engineers who design systems on the

assumption that nothing could possibly go wrong with them are not

utopians, they’re dangerous idiots and they kill people. Assuming that

nothing could go wrong is why they didn’t put enough lifeboats on the

fucking Titanic.

When you read my fiction, you’ll find a lot of stuff breaking down.

Terrorists attack San Francisco and blow up the Bay Bridge in Little

Brother. In Walkaway, economic and environmental breakdown turn the vast

majority of people into “the unnecessariat,” useful only to the extent

that they’re willing to dig holes, climb in and pull the dirt in on top

of themselves. In Masque of the Red Death, civil unrest and societal

breakdowns trigger starvation, cholera epidemics, mass deaths. In When

Sysadmins Ruled The Earth, the people in hermetically sealed

data-centers watch civilizational collapse from bioagents and nuclear

attacks, and debate whether their duty is to keep the internet running

or kill it fast.

So I’ve been here before, lived here in my imagination. Wondered what I

would do. My grandmother used to tell me stories about being inducted

into the Soviet civil defense corps when she was 12, during the Siege of

Leningrad, hauling ammo, digging trenches, hauling corpses, witnessing

cannibalism, while on the verge of starvation, for years. Those

apocalyptic tales have haunted my dreams.

People outside of the former USSR don’t really know about the siege.

They often confuse it with the Siege of Stalingrad, by which they mean

the Battle of Stalingrad, which was also a big deal, but not like the

Siege of Leningrad. 1.5m people died in the siege. It was and remains

the largest-ever depopulation of any city in human history. In the

former USSR, the siege is remembered for the bravery of the people of

Leningrad, their solidarity, and mutual aid.

Every disaster ends with solidarity and mutual aid. By definition.

Because that is the only way a disaster can end: with people pulling

together. If there’s one lesson you should take from Mad Max movies,

it’s that pulling apart in times of crisis only deepens the crisis, and

the crisis will not end until you start pulling together.

It’s not dystopian to imagine the crisis. It is dysoptian to imagine

that in its aftermath, we will all reveal ourselves to have been secret,

barely-constrained monsters who were only waiting for civilization to

hit pause before we started eating each other.

In Rebecca Solnit’s “A Paradise Built in Hell,” the historian uses

closely researched, primary sources to show how, in times of crisis,

everyday people pull together — while elites look on in horror, certain

that the poors are coming to get them, deploying their guards to

pre-emptively strike against their social inferiors (it’s called “Elite

Panic”).

Elite Panic has a curious relationship with storytelling. The tales we

tell ourselves about what we can expect in a crisis informs our

intuition about what WE should do come that crisis. Stories can justify

Elite Panic, or they can rebut it.

I’ve been telling stories about humanity rising to the challenge of

crisis for decades. Now I’m telling them to myself. I hope you’ll keep

that story in mind today, as plutocrats are seeking to weaponize

narratives to turn our crisis into a self-serving catastrophe.

Check out The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow