Environmentalist momentum in the West

By Richard Manning

Originally Posted on Harper’s

August 2017

The best way into Denver is by taking the train to Union Station, a cavernous Beaux Arts building with a barrel-vaulted ceiling, giant chandeliers wrought in brass and milk-white glass, and arched windows as tall as trees. From there, it’s only a couple of blocks to a popular hiking trail. People like to walk along Cherry Creek, following the path as it connects to a highly developed network populated by skaters, mountain bikers, joggers, and dogs. The trail wends through the city center to join another, and then another, along South Platte River, where runners meet kayakers and fly-fishers. More trails splinter off in all directions, but a traveler is likely to veer west, toward headwaters and mountains. You can continue on to Golden, Boulder, ice and rocks, national parks, and solitude.

John Hickenlooper, Colorado’s governor, likes trails. When I visited him in the capitol building, he was wearing a tie and a suit that was a delicate weave of earth tones. A few weeks shy of sixty-five, he had soft eyes set in wrinkles, but he grinned boyishly. He has a reputation for informality, and as we sat down — not at the twelve-foot-wide, U-shaped desk in the middle of his office but at a table by a window — I suspected that the conversation might get rangy.

“Let’s say you want to hike from Aspen up over the Maroon Bells and down to Crested Butte, six, seven hours,” he said. “I’ve done it. I went over the Maroon Bells the second week in August. The wildflowers were higher than my waist. I’ll never forget that the rest of my life.” The trail, he explained, loops “twenty-five of our fourteeners.” This is Colorado patois, referring to mountains higher than fourteen thousand feet. Credibility is gained from a life list of fourteeners that one has “bagged,” i.e., climbed.

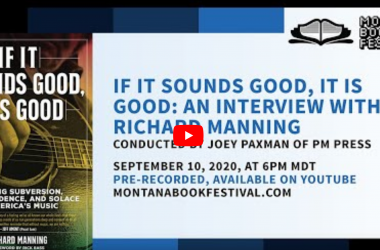

We had arrived at this subject in response to a question I’d asked about politics in the West. Hickenlooper launched into the details of “16 in 2016,” a push to complete the development of that many trails across the state’s wilderness. The program, still ongoing, is an essential part of his plan for economic development — along with music venues, museums, and bookstores. He ticked off the names of clubs in Denver where concerts are held (YouTube videos exist of Hickenlooper playing banjo with Old Crow Medicine Show), and he wanted me to know that his new favorite band, the Lumineers, had moved to Colorado. He also showed me the compact electronic piano that he keeps by his desk.

Conservation, support for the arts — these are key platforms for a politician in his position. In 2014, though Colorado voters chose the G.O.P. for the Senate, they delivered Hickenlooper, a Democrat, to a second term as governor. The state has historically leaned Republican, but in recent years its constituency has changed, and the same has been true across the West, as hiker-progressives have turned districts blue. Last November, Hillary Clinton lost Montana, my home state, to Donald Trump by 20.5 points, but in the governor’s race the nature-loving Democrat Steve Bullock beat a superrich archconservative by 4.1 The states along the Pacific Coast — California, Oregon, Washington — have long been dependably Democratic; now Nevada and New Mexico are trending that way, too. These states, along with Colorado, all went for Clinton last fall.

1 My wife is Bullock’s chief of staff.

Hickenlooper and I left his office and shuttled off to an SUV for a ride across town. In the back seat, as he pored over a speech, he took a call concerning meetings he’d had a week before, at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. He talked for twenty minutes or so, a monologue of arcane details about computer chips on bank cards and surgical joint replacements in livestock — the minutiae of Colorado business. Then we pulled up to a suburban conference center, a bit late.

Inside, we encountered an audience of a couple hundred, dressed in suits. Lunch was served: steak. This was an annual state conference of water users, most of them rural agricultural folks — and, as Hickenlooper noted from the podium, Trump voters. In the arid West, there is a saying that water naturally runs uphill toward money, and conferences like this have been held regularly to impress that on governors. But addressing the crowd, Hickenlooper challenged their exceptionalism, extolling the applicability of big data to water conservation and allocation. “I do see water as the lifeline to every part of the state,” he said. “But I also believe in broadband, that we have to raise some serious money to extend that to every part of the state.” He received polite applause. Someone offered him a beer.

We returned to the SUV. It slithered though a subterranean passageway used by caterers and musicians; we parked, walked through winding halls, and arrived at another auditorium. This one was filled with around three hundred people who had come for the annual conference of Snowsports Industries of America. Here, Hickenlooper and his entourage were wearing the only ties in the room. Most in attendance were dressed in fleece and spandex, eating boxed lunches balanced in their laps: salad, chips, and Granny Smith apples. Hickenlooper joined a panel on recreation, and he opened the proceedings by counseling retailers on how to defeat online competitors.

But then he was back on the trails again, as a way of discussing childhood education and health. Colorado was the leanest state in the nation, he said. “Your self-interest is very closely aligned with my self-interest,” he continued. “My job is to get kids off the couch. . . . We’re lucky if they are outside, in unstructured time outside, ten minutes a day, and they are instead spending ten hours a day in front of a screen of some sort, which every single health measure says is lunacy.”

Of the day’s two audiences, Hickenlooper knew which was growing faster — in Colorado, the recreation industry takes in $20 billion a year and provides nearly twice as many jobs as agriculture. Moreover, he seemed to understand which had become crucial to his prospects in future elections, including, some speculate, the 2020 presidential race. Indeed, political operatives across the West are seeing economic trends that bode well for progressive platforms. In the simplest sense, I learned, their outlook is due mostly to the fact that this part of the country offers voters scenic places to live.