By Jim Patterson

Chapter16

Richard Manning explores the mysterious allure of song

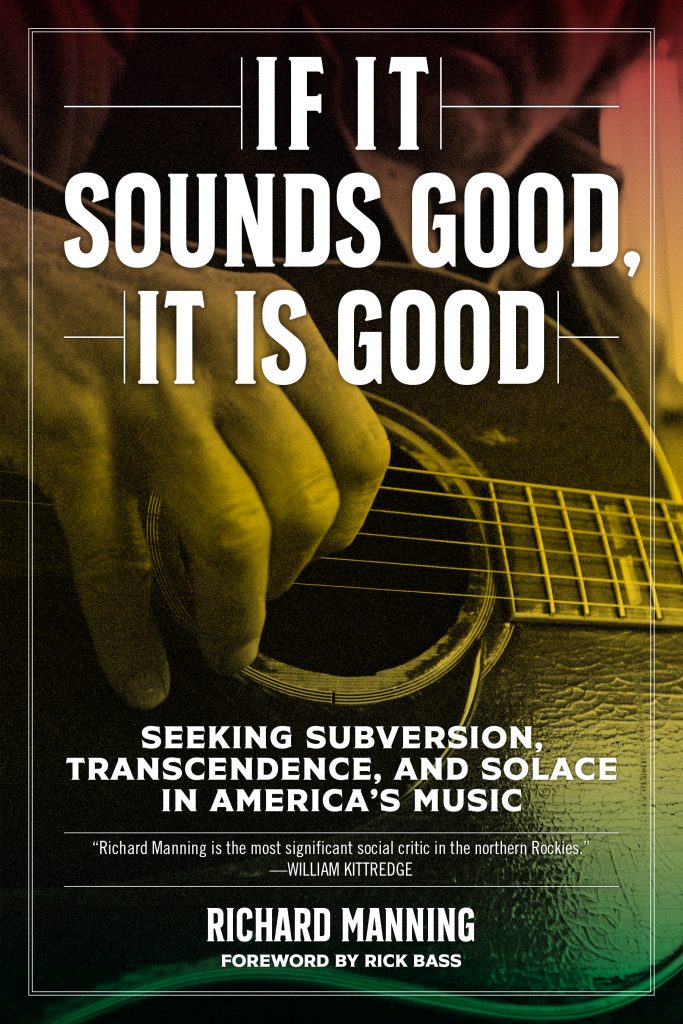

Most of us love music, but Richard Manning is on a mission to explain why in his latest book, If It Sounds Good, It Is Good.

Manning is a contributing editor for Harper’s magazine and was a John S. Knight Fellow in Journalism at Stanford University. He writes mostly about environmental issues, but he’s also a musician with a deep love of American roots music and a pesky case of stage fright. If It Sounds Good, It Is Good is a deep dive into — among other things — how music impacts the brain, why certain guitars sound so much better than others, why the way most of us listen to music is flawed, and why learning to read music can be an impediment to improving as a musician.

That last one will ruffle some feathers, but he has a good argument to back it up. Since he’s an author with 10 previous books to his credit, it also bears mentioning that Manning isn’t all that keen on reading as a learning method. Read on to find out why.

Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Chapter 16: Why do you think music is so critically important to many people? To some it’s just entertainment, but to lots of others it’s an integral part of life.

Richard Manning: I’m convinced music is a necessity. It’s not something that we have as a frill. It’s foundational to the human condition. What it does is give us access to parts of our brain and ways of thinking and understanding that are becoming lost in modern humans. I think its primary purpose is recovering our humanity.

Chapter 16: Is it important that people have some experience playing music, or can you get the benefits by only listening?

Manning: I think you need to have experience directly with the music. You can listen several different ways. You can listen, for instance, as most people do, on your iPad or your iPhone, with lousy earphones and compressed music. Most people have never heard the complexity of acoustic instruments in acoustic space. If you’re listening that way, if you’re directly involved with the music as the listener in the same space as an acoustic instrument, that’s a very different experience. I think you gain a lot by that. Also, there’s not a distinction in many different languages between music and dance. That’s because people were engaged in music by dancing. That’s a valid engagement. You’re moving your body or you’re feeling the rhythm within your body, and you’re internalizing the music that way.

Chapter 16: If you are determined to be a musician, what’s the best approach?

Manning: Playing requires practice, that commitment to learn by developing the skills every day. Practice means almost exactly the same thing as it does when Buddhists talk about meditation. Practice is something we’re lacking in modern life. We think that if we read a sentence and understand it, we’ve learned it. In fact, you really don’t know things until you internalize them and can induce them without thinking about them. So I think that’s really important for the brain that we actually participate in the music, to train our brains to expand our abilities.

Chapter 16: Are you saying that reading books is not a good way to learn?

Manning: We’ve lost that respect for doing things. A lot of perfectly well-off people who had great careers as lawyers or accountants or whatever, go into retirement building furniture, because they’re getting some satisfaction out of that in a way that is quite different than what they had before. The same thing applies to people who paint. That requires practice or control to use your body in some way that is quite rewarding. That’s very much the point I’m trying to make. If you’re not doing something like that — it doesn’t have to be music, it could be other things — that requires that commitment, that engagement, that practice, then you’re missing part of yourself.

Chapter 16: In America, aren’t most of us brought up to see musicians as a rarefied species with some special skill we could never have?

Manning: Absolutely. That’s part of our modern problem. You’ll hear it all the time. People say, “I can’t sing.” Well, there was a time when everybody in a given community would sing all the time. But we think that’s reserved for celebrities, so we have glorified those people and put them above us. That’s the smoke and mirrors that’s going on that has deprived us of a valid experience. In the 19th century, virtually every household had a piano or some kind of a musical instrument, even poor people. People gathered in some way, like singing in their churches. They’d sing at their lodge meetings or whatever. Those things are gone now, and that’s our loss.

Chapter 16: In Ireland, you walk into a pub and it seems like everybody plays music.

Manning: I love Ireland for that very reason. There are great musicians coming out of that tradition and great language coming out of that tradition because people still practice it all the time. It was the same way in the American South for a long time. It only very recently died out. Some communities go that way, certainly in Africa, where people participate in music a great deal.

Chapter 16: Now, the music you’re involved in, folk music in the American tradition, is that music somehow elevated over other kinds of music? Can you get more out of it than listening to a heavy metal record or another genre?

Manning: Yes. Because it contains so much story. I’m a journalist. I’m interested in story. I’m interested in history. I’m getting marvelous histories out of these old songs, American roots music, and it’s fascinating stuff. It encodes something really meaningful, as opposed to “I broke up with my boyfriend last week and I’m sad.” There’ll be a song about the assassination of President McKinley, for instance. Literally, there’s a song about that. That tells me something about that life and makes it accessible.

But music is also participatory. It developed through poor people. Slaves, Irish workers, those kinds of people. That contradicts the elitist attitude toward music. There are evolutionary biologists who argue that music is developed for the leisure class people to do. American music contradicts that so thoroughly. Music really rose up in one-room shacks all over the country.

Once you get into music, you can start finding these strains and threads in many other different areas. For instance, since I wrote the book I’ve been just absolutely enamored with traditional jazz out of New Orleans. There’s a band called Tuba Skinny that you can see all over the internet now. I recommend that to people. They’re street musicians who chose to resurrect what Louis Armstrong was doing in 1925. That’s absolutely marvelous. In tracing down that tradition, I stumbled onto a whole series of guitarists who really did a whole bunch for the jazz guitar in the 1920s and 1930s. They are all Italians from Manhattan. It was this great thing that came out of their culture, out of the fact that they all played mandolin before in the Italian fashion. Then they picked up the guitar and brought all these great things to guitar as a result. Once you start tracing those threads, you can do infinite regression into cultures, and you can touch just about every culture you can imagine in some really fascinating way.

Chapter 16: In the book, you say that songs aren’t created but evolve. Is there any way the music publishing industry can address that in a fashion that makes any kind of sense?

Manning: No. That whole idea of authority and ownership of a creative product freezes everything in place. So you have a financial incentive to do that. In fact, most of the people who actually wrote the songs in a lot of cases, especially in the early going, didn’t make money. The publisher had the rights to it. What Bob Dylan understands and a lot of people understand is that just about everybody who performed before him was doing exactly the same thing. They were plagiarists. We all stand on somebody else’s shoulders.

What’s fascinating about Dylan is, even with his own work, it continues to evolve. He never really performs his own songs the same way twice. Over the years, it becomes something different. I think that’s mostly out of respect for the creative process. It can happen within one individual in his case. But within American folk music, songs changed every night you played them. That’s what kept them alive.

Chapter 16: In classical music, it seems like the goal is to reproduce something exactly, right?

Manning: But even there, people have recovered old recordings from the mid-19th century, 150-year-old recordings of classical music. They listen to it, and it’s nothing like they expected. They’re working from the same notation. So it’s exactly the same score, but it doesn’t sound like what people play today. That’s part of the evolutionary process that goes on.

That’s also part of why music can’t be literal. In other words, it can’t be written down. Because notation is an abstraction. It can only be a very small part of it. I just happened to listen to a lecture a few weeks ago at a festival by a really talented jazz violinist. He analyzed the differences between two eighth notes in swing players, and none of them played it the same. It was down to microseconds difference, which in music makes all the difference in the world. That subtle thing is up to the player. That’s how music evolves.

Chapter 16: But aren’t there geniuses who do new things? I’m thinking about “Strawberry Fields Forever.” As far as I know, there was nothing like that before The Beatles did it.

Manning: Yes. There’s no doubt that’s true. There was nothing like Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five recordings before he recorded it in the 1920s. Now, he didn’t really make it from whole cloth. He had been participating in that music in New Orleans with a bunch of different players. It was just ready for that moment and he pushed it across the line. So yes, he’s a creative genius, but he also was dependent on the people around him. We always need to acknowledge that there’s too much made of the people who do the hot new recording. In fact, what you’re hearing in any form of music has been centuries in evolution to get to that point.

Chapter 16: Is being able to read music in the conventional way a hindrance to learning to play soulfully? Does it restrict people in some way?

Manning: It depends. If that’s all they rely on, it is. That happens a lot in classical music, where people who are technically very good can’t really play as well. I can’t remember the last time I met a guitar player who reads music.

Chapter 16: Really? Not even the Nashville number system or things like that?

Manning: Yeah, a few will. I do a bit of tablature. But most of them don’t do the tablature. They learn by ear. It turns out that’s a pretty good way to learn. What limits you on that is you’re limited to what you hear. In other words, you’re going to end up playing like other people. But we all do. So that cutting-edge stuff that comes straight out of left field is not available to you. I’m not opposed to reading music, but I still think it’s not a complete education. I don’t think it’s even a necessary condition of being a musician.

Chapter 16: Is this a bad time to be a musician?

Manning: There’s no doubt about it, because you can’t make a living in the music business. Only if you’re a celebrity. Thirty years ago, you could have a decent career by being a mid-level musician, and there are a lot of very talented ones around. Now you have to be a celebrity. I know a few studio musicians, but there are fewer and fewer jobs all the time. Part of it is the industry and the way it works. Where you could sell your CD before, now people just download it someplace and rip you off, or the company that posted it rips you off. There’s almost no money left to pay musicians to do what they do.

Chapter 16: Streaming music hasn’t been beneficial to musicians?

Manning: In the book I talk about The Carter Family going to record in Manhattan and not having enough money to eat. Meanwhile, their music publisher is driving a limousine. There’s nothing new about this, but it’s worse now.

Chapter 16: Would you talk a little bit about the role of alcohol and drugs in music? Would some people not become addicted if they didn’t pick up an instrument?

Manning: That’s a good question, and I don’t have a good answer for it. But it’s a question that needs to be asked. … It seems to be most prevalent among people who do improvisation. The thing about improvisation is it’s scary if you don’t know what’s coming next. So if you live on the edge of that all the time, I imagine it’s a pretty frightening experience. But it also requires that you drop those barriers to the free part of your brain that allows you to do that. I think drugs and alcohol are very good at dropping those inhibitions. Then once you’re in that situation or that culture, and everybody else is drinking, then there’s social pressure to do the same thing.

Chapter 16: I’m going to end with this because it’s something about your book that just cracks me up. Why are you so down on singer-songwriters who write introspective songs about themselves?

Manning: I kind of overstate that case. Some of that’s tongue-in-cheek. It’s just there’s way too much of a good thing. You’d be better off if you went and learned all the songs that exist already. The other part of it is when you go to any coffee house, the songs have become so self-referential and self-involved and narcissistic that it’s worthless. It really does not speak to the rest of us in any interesting way.

Jim Patterson is a freelance writer in Nashville. His work appears regularly on the United Methodist News website, UM News. He formerly covered country music for the Associated Press and was a public affairs officer and senior writer at Vanderbilt University.