By Michael A. Gonzales

Shindig Magazine

December 2019

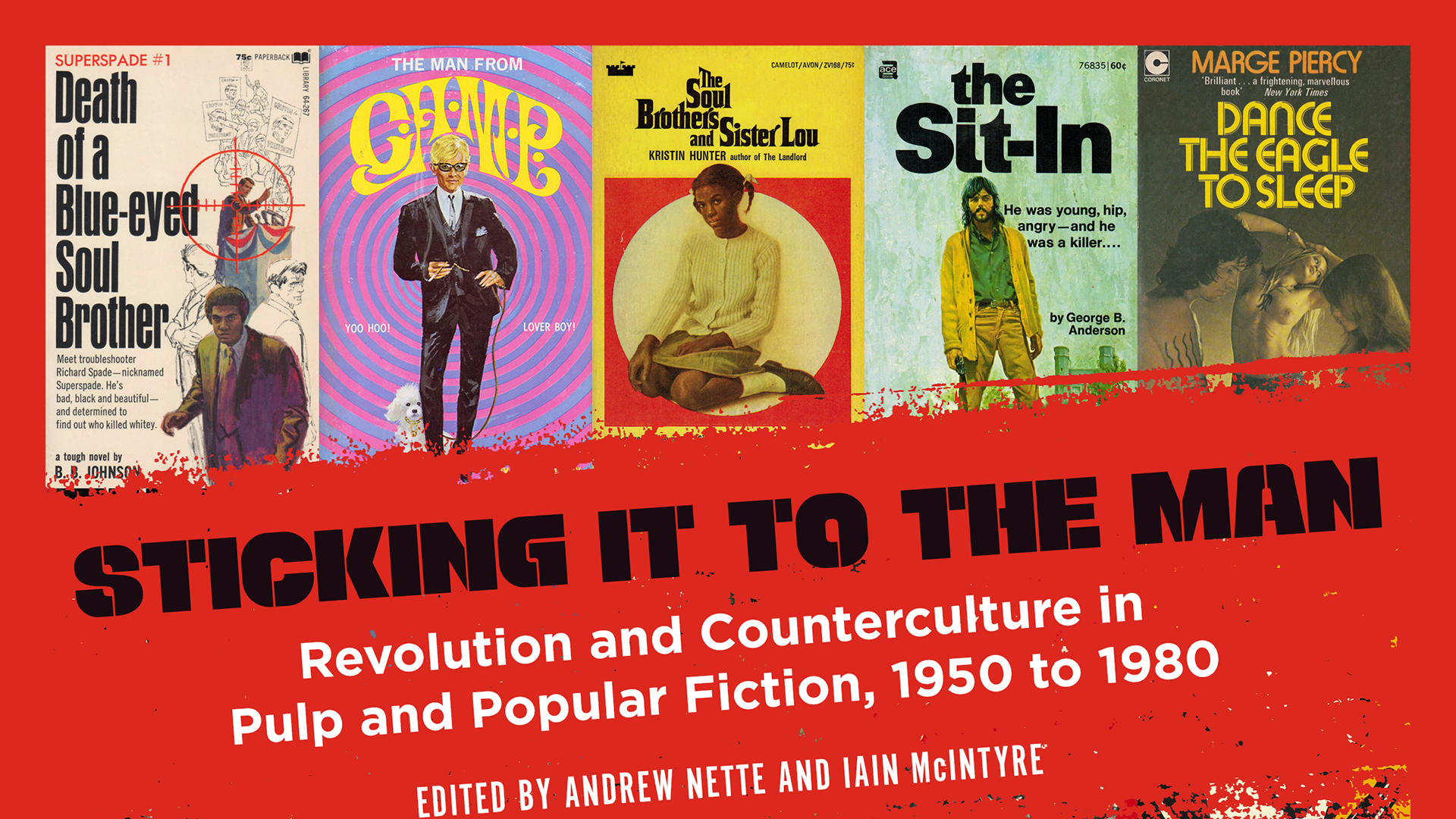

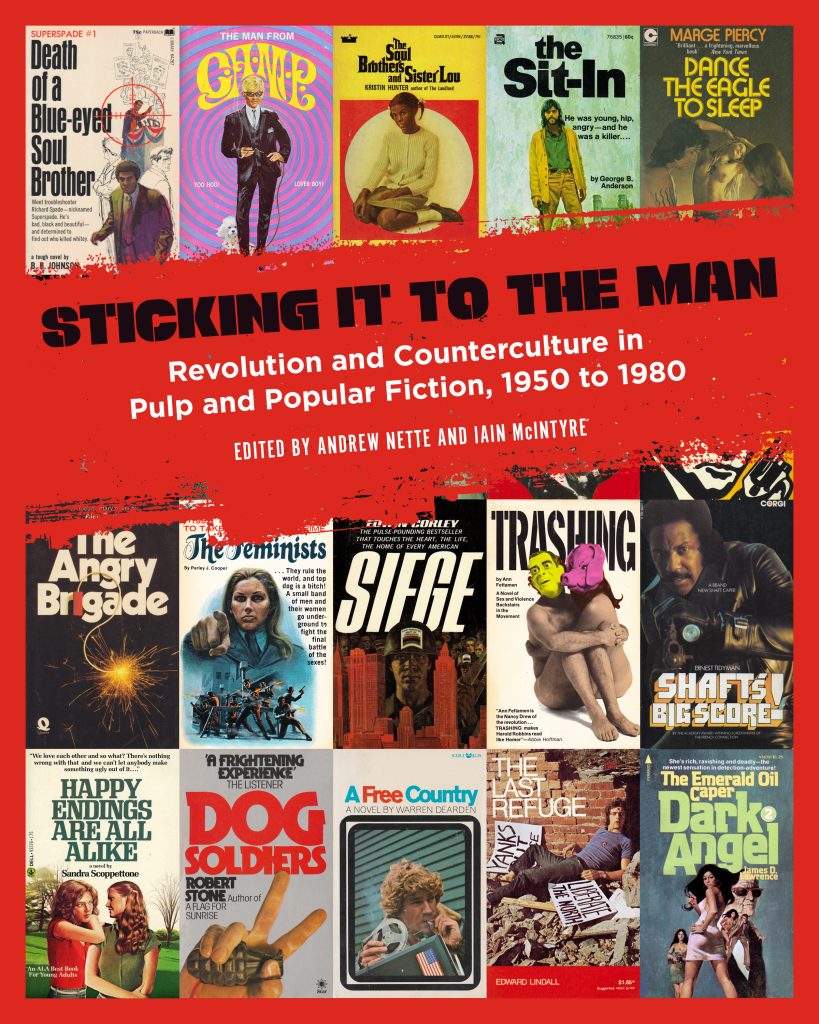

Sticking It To The Man, a new 320-page collection from PM Press, tracks the ways in which the changing politics and culture of the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s were reflected in pulp and popular fiction in the US, UK and Australia.

In this extract Michael Gonzales focuses on the 1971 novel and film that popularized the Blaxploitation genre and won Isaac Hayes an Oscar for his ground-breaking soundtrack, Ernest Tidayman’s SHAFT.

By all accounts, 1971 was a great year for former news- paperman–turned–pulp novelist Ernest R. Tidyman. Along with the paperback release of his hard-boiled debut Shaft, the Cleveland, Ohio, native cowrote the film version for MGM as well as the screenplay for The French Connection. The year before, French Connection producer Philip D’Antoni and director William Friedkin read Shaft in galley form and were impressed with Tidyman’s gritty gumshoe story. “I was shocked when he walked into my office, because I was expecting a black person, because Shaft was about African Americans,” D’Antoni recalls in the 2001 documentary Making the Connection: The Untold Stories. “Not only was he white, but a very WASP-y person from Ohio.”

At the time, Tidyman was a forty-two-year-old former New York Times reporter who began his career as a teenaged journalist for the Cleveland Plain Dealer. After Tidyman’s stint at the Times, he started thinking about writing Shaft. “The idea came out of my aware- ness of both social and literary situations in a changing city,” Tidyman told a writer in 1973. “There are winners, survivors and losers in the New York scheme of things. It was time for a black winner, whether he was a private detective or an obstetrician.”

Three years after the assassination of Martin Luther King, “the black private dick that’s a sex machine to all the chicks,” as soulful composer Isaac Hayes described him in the Oscar-winning “Theme from Shaft,” became a cinematic symbol of Black Power and a mainstream household name. The seminal film also helped birth the 1970s blaxploita- tion film movement that includes Super Fly (1972) and The Mack (1973). The same night Hayes accepted the Academy Award for best song, Tidyman also won a gold statue for The French Connection screenplay. Yet, in Shaft’s forty-year history as a movie icon, most fans of the film know little about Tidyman’s pulp fiction series. Between 1971 and 1975, Tidyman wrote seven Shaft novels, including Shaft among the Jews (1972) and Shaft Has a Ball (1973).

Tidyman’s fourth wife and widow Chris Clark, a former blue-eyed Motown soul singer and screen- writer who was nominated for an Oscar for cowriting the screenplay to the 1972 film, Lady Sings the Blues, describes her late husband as “a big grizzly bear who scared people when he was angry.” Tidyman dropped out of school at thirteen. His police reporter father forced him to get a job at the paper. “My father was an off-campus journalism professor to hundreds of guys who went through the Plain Dealer process,” Tidyman once said.

“It was the other reporters who shaped him as a writer and a reader,” Clark says from her California home. “He was able to bring both street experience and literary knowledge to his material. Ernest often said, ‘Words are a licensed weapon and I never pull them out on people who aren’t good adversaries.’”

In Joe Eszterhas’s amusing 2004 autobiography Hollywood Animal, the infamous screenwriter of Basic Instinct (1992) and Showgirls (1995) shares a few Plain Dealer newsroom stories about Tidyman. “Before I got to Hollywood, when I was a very young newspaperman in Cleveland, I kept hearing from the older reporters about a legendary former reporter who’d wanted to be a Hollywood screenwriter,” Eszterhas writes. “He was a legendary drinker and gambler—legendary, too, because he’d been fired from the newspaper for steal- ing a wristwatch from a jewelry store where he’d gone to cover a holdup.”

In a phone conversation, Clark describes her late husband: “Larger than life, he was about six feet one and a big guy. We met on a blind date after talking on the phone a few times. I was thirty-six and he was in his early fifties. When he proposed to me, I had never been married and, after his having three wives, I couldn’t understand why he wanted to get married again. He was a complex man who was full of rage and civility, but he also played violin beautifully.”

John Shaft, in contrast to his creator, was a Harlem born former foster child and street tough who kept an office in (then) seedy Times Square and knew mili- tant leaders by their first names. While Tidyman’s character is one of the most popular black detectives in crime fiction, he wasn’t the first. In 1932, Harlem Renaissance author Rudolph Fisher wrote the earliest “Negro” detective novel The Conjure Man Dies (1932). Since then, many other books have featured African American detectives including Chester Himes’s A Rage in Harlem (1957) featuring NYPD detectives Coffin Ed

Johnson and Grave Digger Jones, John Ball’s gentle- manly Virgil Tibbs of In the Heat of the Night (1965) and, more recently, James Sallis’s brilliant Lew Griffin series.

Los Angeles mystery writer Gary Phillips, who created black private eye Ivan Monk, felt the spirit of Shaft hovering over his shoulder while writing his own series, beginning with Violent Spring in 1994. “Certainly, I wanted some of Tidyman’s toughness in my guy,” Phillips says. “Though I was, hopefully, careful not to take it to the extremes of where Tidyman could take his action and violence.

“In a certain way, Shaft was a brother’s answer to Spillane’s Mike Hammer,” Phillips continues. “The novels speak to a time and [its] sensibilities from the sexual loosening [of morals] then, the Black power movement, Vietnam, to our disillusionment as a country with our institutions given the five o’clock shadow of Nixon hangs over those books.”

When the movie Shaft was released by MGM in the summer of 1971, it was instantly successful and helped save the studio from financial ruin. Directed by Life photographer Gordon Parks, who hired screenwriter John D.F. Black to rewrite Tidyman’s initial script, the title role played with vigor and swagger by macho model-turned-actor Richard Roundtree. “Tidyman wasn’t happy with the film, because he felt the charac- ter had been politicized,” says frequent NPR commen- tator and author Jimi Izrael, who wrote his graduate thesis on Shaft. “His feelings were that he had written Shaft as a detective novel, not a Black Power tome.”

Clark, who called out director Gordon Parks in a 1991 LA Times article for failing to mention her late husband in his autobiography Voices in the Mirror (1991), agreed. “Ernest felt the movies had made Shaft into a comic book character,” she says. “Ernest couldn’t understand why the filmmakers felt a need to change him. He was especially disappointed with the last one (Shaft in Africa, 1973).” Still, Tidyman’s unhappiness didn’t stop him from penning the successful sequel, both the novel and screenplay for Shaft’s Big Score! in 1972.

“I think the critics have overrated the movie Shaft,” says British writer and editor Maxim Jakubowski. In 1997, Jakubowski served as coeditor of a line of book reissues for the Bloomsbury Film Classics series. “Although there wasn’t a big demand for Tidyman’s work, I included Shaft in the series, because for so long the movie overshadowed the book. It was a natural one to do.”

Novelist Nelson George, who described Shaft as one of “the only black superheroes we knew” in his 2009 autobiography City Kid, is a fan of Tidyman’s work. “Richard Roundtree was charming on screen, but the Shaft in Tidyman’s novel is a richer character in many ways,” George says. “In the book, the charac- ter is meaner. We find out his backstory as an orphan and Vietnam vet. None of that is even mentioned in the film.”

In 1975, Tidyman penned The Last Shaft, the book where he put to death his creation. Shockingly, Tidyman chose to have a random mugger murder Shaft in the last paragraph. “What is this bullshit?” are his last words. “Ernest prided himself as a craftsman who had a great ear for dialogue,” explains Chris Clark. “He was juggling a lot of projects and characters and he felt the quality of the Shaft books was slipping. That’s why he decided to kill off the character.”

But while the novels of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler receive spiffy reissues and beau- tiful Library of America editions, the Shaft books have languished out of print for years. (The original novel was finally republished in paperback in 2016.) “Although [Tidyman] was not on a par with Hammett and Chandler, he wasn’t far behind,” says Woody Haut,

author of Heartbreak and Vine: The Fate of Hardboiled Writers in Hollywood (2002). “While I wouldn’t rate Tidyman as a noir innovator, he was an authentic tough-guy writer whose work, at its best, is a cross between Chester Himes and Mickey Spillane. His protagonists on the page and screen retain a sense of ethics and some vestige of a political consciousness, while maintaining ties with the criminal world, often blurring the distinction between the two.”

Although other contemporary novelists of the period had no problem appearing on talk shows drunk or pitching brews in beer commercials, Tidyman, according to Chris Clark, “Had no interest in selling himself; he’d rather write than promote something he’d already completed.”

In 1984, at the age of fifty-six, Ernest Tidyman died in Westminster Hospital in London of a perforated ulcer and complications. Decades later, with the excep- tion of the first book, the Shaft series is still out of print. According to The Best American Mystery Stories series editor and Mysterious Bookshop owner Otto Penzler, it is not surprising. “For big publishers to keep books in print, they have to sell about two hundred copies a week, 10,000 books a year,” Penzler explains. “You have to realize, those Shaft novels never had such a big print-run in the first place. Unfortunately, a lot of people don’t even know Ernest Tidyman’s name.”