Angry Workers World

November 26th, 2019

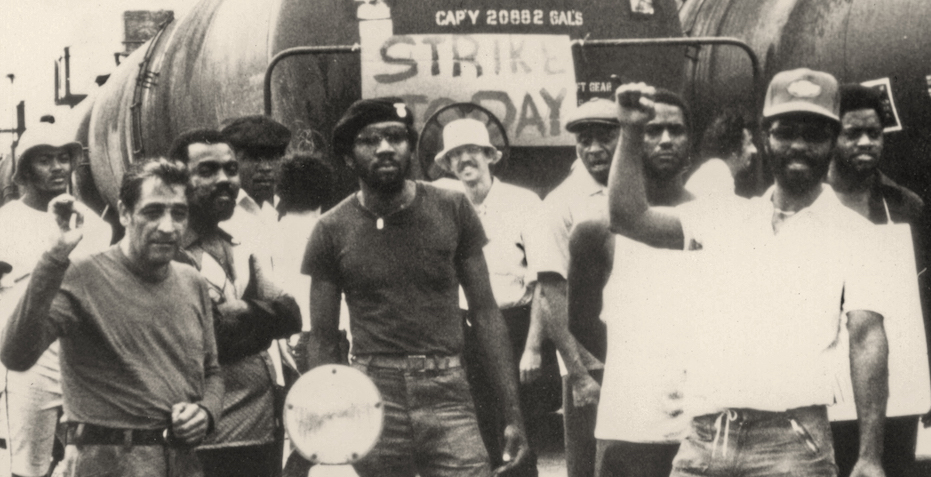

This book is a thoughtful and easy-to-read account of the author’s experiences in various industrial workplaces in the US in the late 1970s and early 1980s. We’ve all heard about militant steel workers in Chicago, but there was a lot more going on than that, and at a variety of workplaces, many of which never made the headlines. Dave’s book takes us through some of these stories, as we learn about the shop-floor dynamics, the relationships with his co-workers, the ways work is organised, racial divisions, how to oppose migration raids and the nightmares of coming up against the union bureaucracy. The depiction of personal lives and relationships is really touching. The best way to get a feel for the book is to read this interview with Dave:

https://www.jacobinmag.com/2019/02/david-ranney-living-dying-factory-floor

The humble approach of the author makes him a personable and likeable guy. Even though he was a militant (in political organisations like Sojourner Truth Organisation and News and Letters), he wasn’t sent to the factories to organise or for research purposes. Instead, it was his political compass that made him decide to leave his academic job and work in factories, to get some real understanding of how things worked and what was going on. He doesn’t shy away from the differences between his background and the background of most of the other workmates, but he also explains how this difference doesn’t prevent a common struggle and learning from each other.

The strong point of the book – its un-ideological account of experiences – is perhaps also its main weakness. From a political point of view it would have been interesting to get to know more about how his personal experiences on the job related to strategical debates about shop-floor interventions in organisations like the Sojourner Truth Organisation (STO), in which he had taken part. While Dave’s humility is very likeable – the fact that he was not entering the workplace with any pre-conceived goals – it doesn’t help us much when it comes to political debate. It would be good to hear Dave’s take on some of the strategic debates within STO, documented in Michael Staudenmaier’s book, ‘Truth and Revolution: A History of the Sojourner Truth Organisation’.

From this, we learned that the Sojourner Truth Organisation stood out from other far-left groups in two regards:

a) they saw the trade unions mainly as a means to integrate class struggle and therefore largely abstained from trying to get union rep positions

b) their answer to racial divisions within the working class in the US was not to find issues or demands that could easily unite white and black workers, but to focus the attack on the dividing lines, e.g. the fact that black workers were much less likely to be hired into higher skilled jobs

It would have been good if Dave had reflected more on how these political positions corresponded – or clashed – with his experiences on the job.

While ‘taking on working class jobs’ might be smiled upon nowadays, it is still acceptable as an individual act of widening one’s horizon, like a youthful dabble with hallucinogenic substances. In contrast, to proclaim this as a collective and strategic act like STO and many other groups did is frowned upon and deemed as vanguardist or voluntaristic. In the early 1970s STO comrades got jobs strategically, at Steward Warner instruments manufacturing plant, Motorola or the International Harvester plant in Chicago. They published workers’ newspapers, such as the ‘Insurgent Worker’ or factory newsletters such as ‘Talk Back’ or ‘Workers Voice’.

“All these publications shared a common approach, using to-the-point arguments and avoiding obscure political jargon, while stoking controversy whenever possible. Issues specific to particular departments were given as much coverage as plant-wide problems, in an attempt to broaden worker interest and solidarity. Particularly corrupt union officials and especially hated foremen and managers were routinely criticised, insulted, and mocked by name. Instances of collective worker action, be they spontaneous or well planned, were reported as models to emulate. But STO understood that the goal of publishing such shop sheets went beyond simply providing information to workers. Hamerquist worked at Stewart-Warner when Talk Back was first initiated, and in an early analysis of the group’s workplace efforts, he argued that “Since the function of leaflets and newsletters is not just a general education or agitation, but to help create a base of independent organization, they must aim toward mobilizing the workers for certain specific struggles. It can easily happen that the literature can make threats, pledges, and calls to action that it can’t back up with a base of real strength.” (Staudenmaier’s ‘Truth and Revolution’)

Over time and with the changes in class struggle around them, the debate about the relationship between day-to-day struggles at work and wider political organisation intensified within STO.

“One tendency within STO was labeled “workerist” because of the emphasis placed on integrating as fully as possible with the working class. In many cases, this manifested itself in the adoption of common working class attitudes, including eventually a willingness to work with the trade unions. (…) From the perspective of those who remained in STO for the long-haul, these people were inevitably lost to the struggle, as they made their peace with the unions, and with the day-to-day realities of working class life. On the other hand the workerist attitude was an important corrective to the woodenness or posturing that characterised much of STO’s early work. In the end, a split in the organization over these issues would mark the conclusion of STO’s initial workplace period.”

Debates about whether or not to take on roles as shop stewards became more heated.

“By late 1973, conflict came to head at the meeting where members reviewed the previous year’s work. (…) In advance of the meeting, Goldfield and another STO member named Mel Rothenberg drafted a paper titled “The Crisis in STO,” which was subsequently signed by seven additional members of the group, including the entire Westside branch. In many ways, this document skirts the trade union issue, preferring instead to argue its points on the plane of STO’s party-building efforts and the question of correct interpretations of Leninism. (…) “The Crisis” begins by asking a number of critical questions about difficulties that the Westside branch had encountered in organising at the International Harvester plant: “Why has so much direct action at Melrose not contributed towards the development of a growing, stable, independent organization?… Why have we been unable to build a sustained, coherent, credible alternative to trade unionist forms of struggle?”

This faction criticised STO’s emphasis on the role of ‘immediate experiences of independent struggle’ for the development of revolutionary consciousness. Instead they pointed out that rather than focusing on ‘single moments of direct action’ as catalysts of consciousness the organisation should return to Lenin’s understanding that the acquisition of revolutionary consciousness is a longer-term process where day-to-day ‘spontaneous consciousness’ interacts with ‘socialist consciousness’ obtained through collective reflection. To become shop stewards was interpreted as a step towards this longer-term process. A second faction emerged – the ‘Tool Box’-faction – which questioned the need for a centralised political organisation and proposed to turn STO into a “service organisation to workers, not a leading body of any kind”. STO would split multiple times.

Some of these debates seem tedious and abstract in hindsight, but they were led against the background of both concrete experiences at work and interpretations of historical lessons. Dave himself left STO as the organisation turned away from its workplace focus towards ‘organisation building’ within the left and ‘national liberation struggles’. It would be interesting to know how he interprets these debates on the basis of his own experiences – which he made several years after the actual discussions within STO. For example, although he didn’t become a shop steward at the places were he worked, the main wildcat strike developed out of a dispute over the trade union negotiated contract. In a different factory he supported the creation of an independent trade union, despite being wary of its leadership.

Similarly interesting would be to reflect about STO’s line on class and racism. STO’s criticism was that the left’s focus on issues where black and white workers could easily unite avoids addressing issues which cement racist hierarchies within the class, e.g. who can become a skilled worker, who can live in certain areas, who gets pulled over by the cops. They see that this unity is build on shaky feet and that the bosses will be able to destroy it easily by using ‘white-skin-privileges’. While this position might be historically founded and theoretically correct, it nevertheless puts consciousness before practical social relations. How can and why should black and white workers strive for class unity if this striving is not based on experiences of common struggle? It’s in struggle that things are aired, not beforehand.

Dave’s own experiences point in this direction, as he himself emphasises the role of the wildcat strike to bring the Mexican, Black and the few white unskilled workers of the factory together. At the same time we don’t hear much about his own analysis of why Black workers found themselves mainly in the unskilled jobs in the first place. He hints at management practice, but that in itself cannot explain things.

At this point we recommend listening to an interview with another STO member, who sadly left us recently, Noel Ignatiev. The interview is interesting, but the interviewer also fails to ask how STO’s line on racism went hand in hand or clashed with STO’s emphasis to promote workers’ independent and direct action. How did it inform STO’s workplace activities on a day-to-day level?

Dave’s book, as part of this wider historical and political context, is a valuable and enjoyable contribution to the realities of day-to-day struggle. We recommend you get yourself a copy!