By Paul Bishop

Paul Bishop Bookshop

December 3nd, 2019

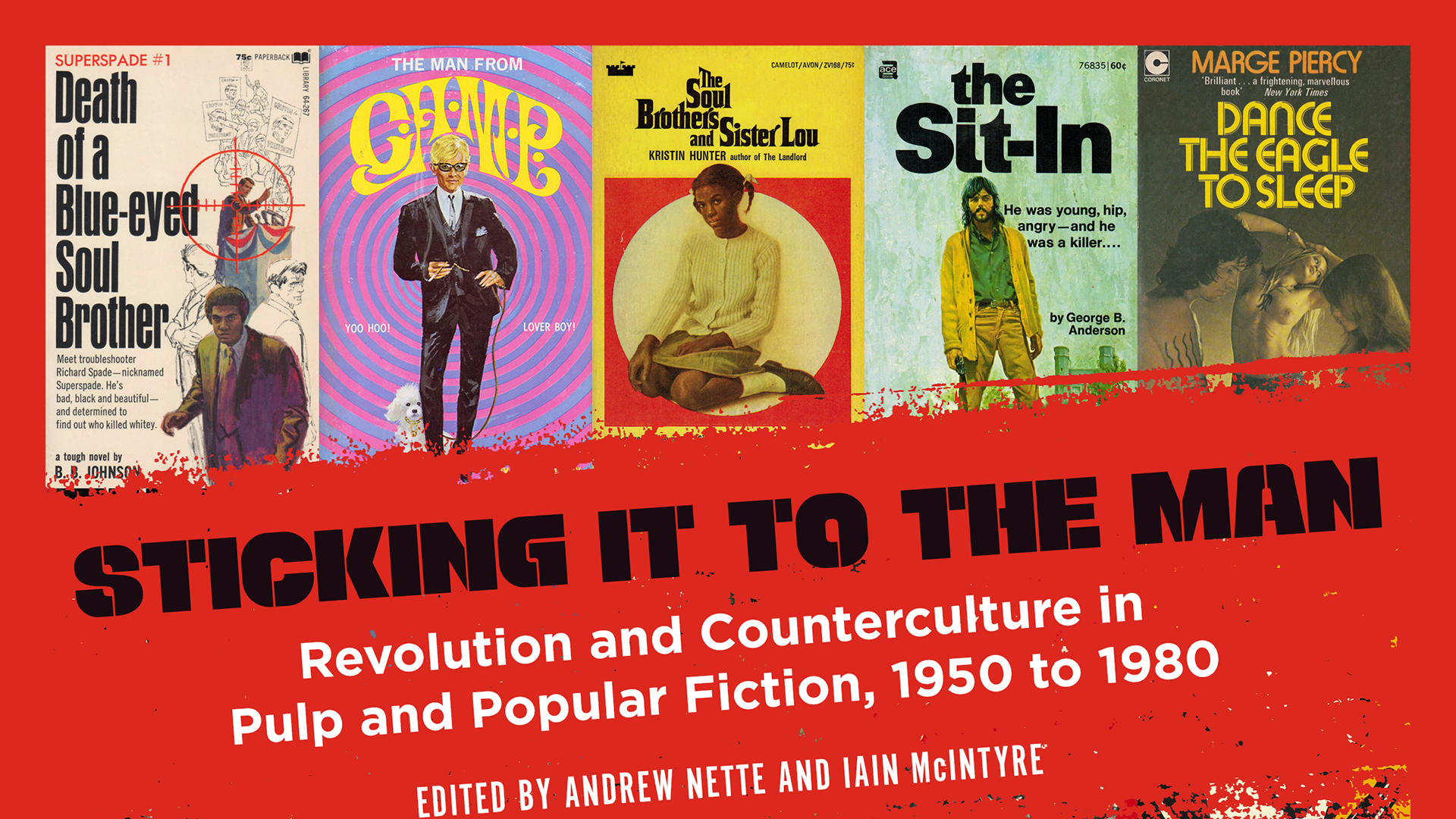

I can’t express how much I enjoyment I received from reading every page of Sticking It To The Man—Revolution and the Counter Culture in Pulp and Popular Fiction, 1950 to 1980. I can’t recommend it highly enough. Fascinating, well written, filled with an amazing array of beautifully reproduced vintage paperback covers, and endlessly entertaining subject matter. This endorsement should be more than enough for those of you who know me—and know I don’t gush over much—to delay reading further and immediately swing over to your chosen Internet book source or head out to your favorite independent bookstore and order a copy.

Don’t worry, I’ll wait…

Stop reading…Go order…I said, I’ll wait…

Okay…You’re back…If you’re into instant gratification and

downloaded your copy of Sticking It To

The Man, feel free to skip out on this post and jump right in to the

electronic pages of a book you’re going to find way more interesting. If you’re

old school and have to wait for your copy to be delivered, you’re

welcome to hang out, but hold on ‘cause I’m gonna drag you down a rabbit

hole…

Having spent thirty five years serving with the Los Angeles

Police Department, there is no doubt the counter culture of the ’60s and ’70s

would have seen me as The Man. Not as

in you da man, but as in the jackbooted,

oppressive, heavy-handed authority figure and violent stooge who needs to be

eliminated in the coming radical civil war. You know—The Man who needs sticking it

to.

Fortunately, that stereotype is as false and prejudicial as

most stereotypes, but you still might not think I’m the intended target

audience for a scholarly, yet eminently readable reference tome entitled, Sticking It to the Man: Revolutions and

Counterculture in Pulp and Popular Fiction, 1950 to 1980.

You would be wrong…

I was fifteen years old when I first read Pimp by Iceberg Slim. A voracious reader

of everything I could find at the library or stretch my very limited budget to

buy off the spinner racks, I haunted a regular round of bookstores and other

retailers who stocked shelves of paperbacks.

Occasionally, I found my way to an old fashioned open air

newsstand on the corner of White Oak and Ventura Boulevard in the San Fernando

Valley. There, perilously close to the forbidden section containing dirty

magazines and sleazy books of a questionable moral nature, was a double row of what

appeared to be angry Black-centric paperbacks.

These always fascinated me. The

books were new, but exposure to the open air had turned their covers grubby and

slightly warped the interior pages. Still, they seemed to call to me with an

illicit promise of exposure to another world I vaguely knew existed, but had

never experienced.

Most of these paperbacks were produced by Holloway House, a

shabby down market publisher with a shady reputation. I was totally unaware at

the time of Holloway House’s ironic nature—being run by two white publishers who saw the uprisings

in Watts and other black neighborhoods across the country as a crisis of

representation, a cultural void they could profit from by publishing cheap mass-market

paperbacks targeted specifically toward a black working-class readership.

As a

fifteen year old white kid, I only knew Holloway House’s crappy bindings,

cockeyed cover printing, and poorly chosen graphics lived in a world total different

to the traditionally published paperbacks I was used to reading—where James Bond

was considered risqué.

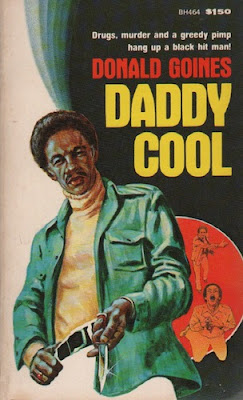

Books by Iceberg Slim and his protégé Donald Goines

dominated the small selection. Alongside them were the lurid pulp-style covers of men’s

adventure series featuring Black anti-heroes such as Radcliff, The Iceman, Kenyatta,

and Joseph Nazel’s pointedly named character, Black. And hidden deep in the mix

were Chester Himes’ blacker than black cops, Coffin Ed and Gravedigger Jones—two

police detectives constantly caught between two worlds and accepted in neither.

I found myself compelled to buy a copy of Iceberg Slim’s Pimp. Maybe it was my own questioning

counter culture leanings. Maybe it was the driving quest I’d had from a young

age to seek out the authentic otherness of cultures outside of my own white

bread existence. Maybe, at fifteen, I was being seduced by books reeking with

the promise of something dangerous and purient—something not to be caught

reading by judgmental adults.

Whatever it was, I plunked my money down on the

counter. The grubby, unshaven clerk gave me the stink eye, but never the less

rang up my purchase. Smuggling the book home, I cracked open its pages as I sat

on the floor of my bedroom with the door closed and the light low—life was

never the same again.

An only child, I immigrated to America from Britain when I

was eight. I had a prissy English accent, prissy English manners, and my

bi-polar mother insisted on dressing me like Little Lord Fauntleroy—I am not

exaggerating. You can imagine what going to school was like for me in the late

sixties surrounded by California kids who were either cool surfers or hard-edged greasers.

Yeah, you get the picture. I’m not whining, but it weren’t pretty. I was

intimately familiar with the inside of school lockers and trashcans on the

quad.

However, in the pages of cheap garish paperbacks by Iceberg

Slim, Donald Goines, and Joseph Nazel, I found a connection to the experiences

of another culture which was also getting its ass kicked—they were the crack

in the door opening me to a whole different cultural world view. And then there

was the startling reality of the character’s representing the downtrodden cultures

in those books refusing to back down and being ready to fight.

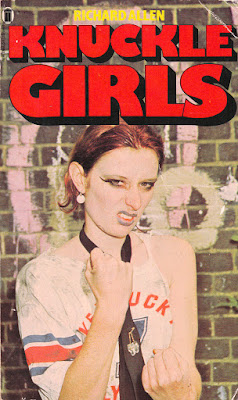

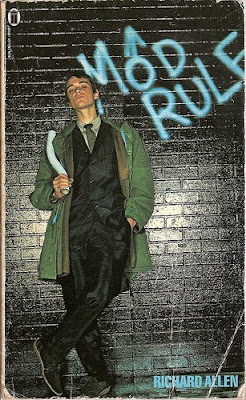

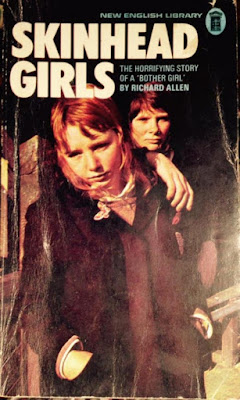

At the same time I was discovering the words of Iceberg Slim and

Joseph Nazel, I also fell into the vast array of sordid NEL (New English

Library) paperbacks, which exploited any and every radical, rebellious, angry

British youth subculture from skinheads to boot boys to terrace terrors to mods

and rockers, and more. These took a little finding, but on trips back to

Blighty, I trolled the used bookstalls at the open air markets in London and

regularly stashed a supply in my suitcase when returning to California.

In both the black pulps and the low-end British trash

novels, I found a weird sort of encouragement. Like the characters in these books,

I was tired of taking crap and made a conscious decision to fight back. If I

was going to get my fifteen year old ass kicked anyway, I might as well do as

much damage going down as I could.

After collecting enough bruises to fill an emergency room, I

eventually learned to fight—and fight dirty (it’s amazing how much harder you

can hit with a roll of nickels in your fist). I became intimately familiar with

the principal’s office, but somehow never got expelled—mostly due to selectively

reverting back to my prissy accent and prissy manners when needed. I began

dishing out more damage than I took, and it didn’t take long before the bullying predators

went in search of easier prey.

My reputation stuck. When my wife forced me to

go to our 20th high school reunion, the first three classmates we encountered

looked at me and said, “Oh, you were the kid in all the fights.” Yeah, that was

me.

There was another surprising layer to many of the works that

mainstream society dismissed as not worth the paper to publish. Some of the

authors were screaming out their rage and pain on the page. Others were simply

trying to make a buck in a hustler’s world. Whether consciously or

subconsciously, their stories of fighting back, of fighting for self-respect

(or their world’s version of self-respect), there was also a thread that spoke

to righting wrongs and protecting others who couldn’t protect themselves.

In my autodidactic way, exposure to these fictional counter

culture pulp radicals led me to read Malcom X, Lenny Bruce, Martin Luther King,

Gandhi, Budda, and many other real life extremists and activists—all of whom

enforced and drove home the message of battling for self-respect and lifting up

others in the effort.

This long ramble has been to build the groundwork for why I

have been so profoundly moved by the impact of Andrew Nette’s and Iain McIntyre’s

Sticking It To The Man has had on me.

Within its covers, I was transported back to the raw emotions and desperate

struggles I’d first found in Pimp, Whoreson, Swamp Man, Howard Street,

A Rage in Harlem, Skinhead, Suedehead, Hooligan, and

so many more.

Sticking It To The Man

is filled with radical delights—Vietnam fiction, the beginnings of gay and lesbian

fiction, paperback original men’s adventure series, retrospectives on Iceberg

Slim, Donald Goines, Joseph Nazel, Joseph Hansen, Ernest Tidyman and Shaft—if it

was radical and it was captured in paperback between 1950 and 1980 it’s part of

Sticking It To The Man.

Finally, circling back to what I learned from radicalized trash fiction.

After thirty-five years

with the LAPD, I find myself now as a nationally recognized

interrogator. I’m

good at what I do. Immodestly, I’m very good. Those who I’ve sat with in

an interrogation room have never met a Machiavellian nightmare like me.

But I got here because of the two most important things radicalized trash fiction taught me.

First, to be an objective enforcer of the law without regard to race, religion, sexual orientation, affiliations, past behaviors, or anything else used to derisively judge another human.

Second, and more importantly, radical trash fiction taught me truth is not a set point…truth is about individual perspective viewed through the lens of the shit that happens to you in life.

The recognition of my quest to understand the nature of truth, and attempt to objectively get as close to it as possible in highly emotional situations, began when I read a book by Iceberg Slim, which I bought from a crap hole newsstand so many years ago. And I’m thankful to Sticking It To The Man for reminding me where I came from and how I got here today.