By Simone Zelitch

November 17th, 2019

I have no record of my first letter to Ursula K. Le Guin. I’ve kept identical black notebooks since I was fourteen, and I looked at the first ten of them and couldn’t find a record of what motivated me to write. The letter must have gone to Avon, her publisher at the time. What I do know is the date of her reply: On Febrary 19th, 1980, when I was seventeen. I wrote in all caps: “I GOT AN ANSWER FROM URSULA LE GUIN”.

And this wasn’t just a note. It had a typed envelope and the letter inside was typed on stationary with Le Guin in curly typeface. She thanked me for what I said about the production of The Lathe of Heaven. Then, I must have asked her about the anarchism in The Dispossessed because she went on “The major source for ODO’s [caps all hers] is probably Kropotkin.” Then, after a few lines about Emma Goldman (“she was such a sweetie”) Le Guin ended, “I fully agree with you that you are going to be a writer. I don’t know why. I just believe you when you say it.”

Of course, I sent her a terrible short story, and she sent back her response, a typed single-spaced savage page. Now, thirty-eight years later, I think: What established writer does this sort of thing? I actually suspect that Ursula did this sort of thing, and all the time. I have no real evidence, and a hasty Google search for stories like my own only led nowhere. Of course, we all know that a generation of writers—particularly women—are in her debt. Of course, we can turn to the back of books—particularly books published by independent presses—and see her testimonials. Yet why do I assume that some of those women had been corresponding with her for a decade or more before that publication? When she died, were there dozens of women pulling out their forty-yea- old letters or postcards? Did they save them in a box like I did?

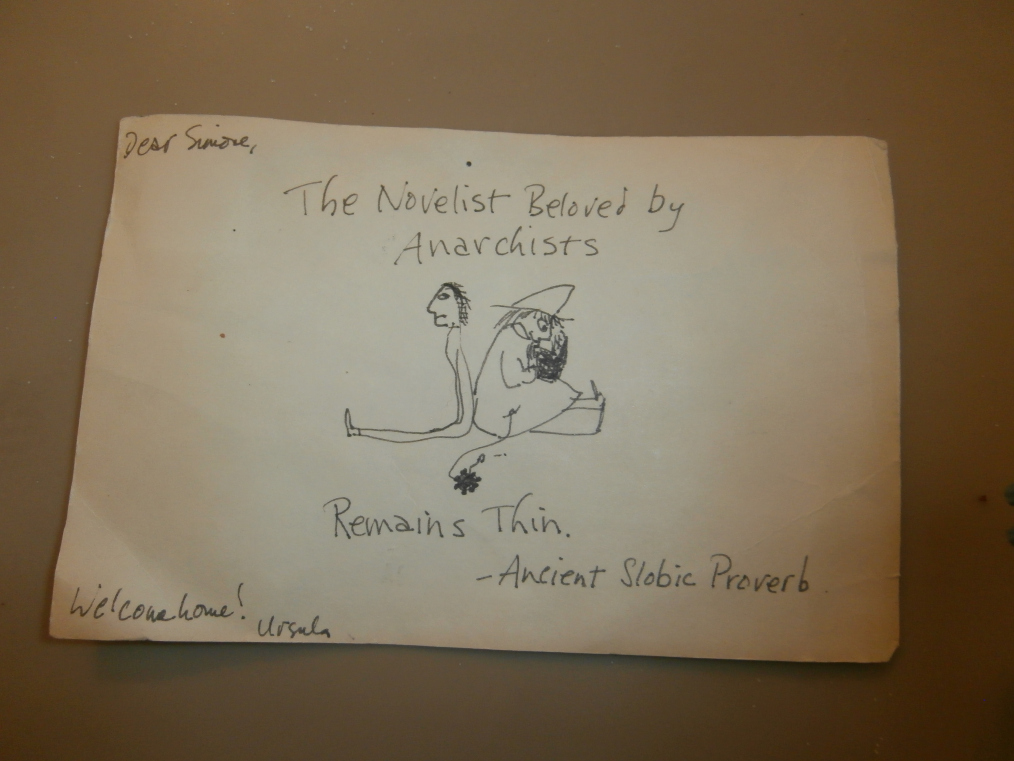

In my case, after that early exchange, with the exception of a letter which generated a weird little postcard based on who-knows-what with a drawing of “smiling running shoes” I swore I wouldn’t write to Ursula Le Guin until I had something to say. Ten years later, my novel about a failed medieval fourteenth- century peasant revolt was published by Black Heron Press. , Le Guin did like the book, and the testimonial she wrote on the back didn’t save The Confession of Jack Straw from obscurity, but it probably was the reason why the book ended up on the shelf of Wooden Shoe, an anarchist bookstore. I told her so, and she sent a postcard: “The Novelist Beloved by Anarchists Remains Thin – Ancient Slobic Proverb”.

Somehow, when we met in person our relationship felt more abstract. The first time was soon after my marriage, in 2002. We met outside of Powell’s, and then the two of us head to her place. She was even shorter than I thought she’d be, brisk, almost businesslike, though by all measures, glad to see me. As we entered her house, she told me that she and Charles had just finished reading War and Peace out loud to each other; when I arrived, he was hiding somewhere. Our conversation was collegial enough, but I do remember her saying something about the importance of women writers having mentors, which made me feel a little too much like a project.

The second time I saw Ursula was in 2014 at the conference of the Association of Writers and Writing Programs in Seattle. By then, she was an established literary lioness, known for her of thunderous roaring, particularly against corporations like Amazon. Her emails from the carefully anonymous address were lots of fun. “I hope we can met LIVE! IN PERSON! at AWP.” And finally, as we arranged to meet her in hotel room, “If you need to be in touch with me after Thursday of next week—try my hotel room. Email no good. Zog not travel with computer. Zog very primitive. 4:30 at Zog’s hotel room.”

She said she’d lost her copy of Jack Straw, and I brought a new one plus the two other books I’d published, half a bottle of wine, and a small bouquet of tulips, and there she was, compact as ever, now a little hunch-backed, with her characteristic cap of straight, white hair. She put the flowers in water and offered me some bourbon from a flask which, of course, she took, and we talked about publishing. She was a happy, witty talker. She said, “You’re a mid-list author” and I wanted to say, “No, actually. I’m not on a list at all,” but it did give us a way to talk about the world of publishing, about marketing and boycotting Amazon of course, and how she resigned from the Author’s Guild over their compromise with Google. Then, slowly, the room began to fill with other white-haired Oregonian women, all clearly over eighty; one of them was Ursula’s webmaster. They passed around that flask; one of them took a glass out of the bathroom and took off its little paper cap to pour. I began to feel as though I shouldn’t overstay my welcome.

After that point, Ursula and I corresponded only by email, and not very often: When David Hartwell at the the big science fiction press, Tor, bought my novel Judenstaat (she warned me that some other women he’d published had found their books buried), when Hartwell demanded a blurb from her (She’ll get to it and see if a blurb “rises up”; it didn’t), when Hartwell died suddenly leaving my novel orphaned (He was a star, and I’d be treated well; unfortunately, I wasn’t). Somehow, the medium of email didn’t suit either of us. I missed the squibby pictures on her postcards. I also wondered if somehow my publication at a press like Tor made me less interesting. I did write to congratulate her on her inclusion in the Library of America series, and particularly her selection of her wonderful and mostly-forgotten Orsinian pieces in the first volume. I didn’t get an answer.

I’m fifty-seven now, older than Le Guin had been when she first got my first letter. My response to her death was pretty straightforward: I’m grateful that she was honored in her own time-time, that she got to write what she wanted to write, and that her work and opinions continue to matter. She also died before her husband Charles, something that I suspect she would have wanted; you can feel the strength of that relationship in every book she’s written.

And maybe I understand why Le Guin might have answered all those letters from strangers. She wasn’t being altruistic. An anarchist in the Ododian mold doesn’t believe in altruism. Rather, she believed in solidarity in a broad sense, between writers and readers against the forces of markets that tell us what we have to write and algorithms that tell us what we want to read. As Kropotkin writes, “the great principle of Mutual Aid which grants the best chances of survival to those who best support each other in the struggle for life.