By Simone Zelitch

One morning, I was lying in bed with my husband, and I said, “What if a Jewish state had been established in Germany after the war?”

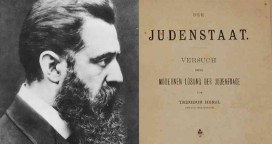

The very idea was a provocation. Yet I continued to consider: if Theodor Herzl was right when he wrote Der Judenstaat in 1896, and the only answer to what he called “the Jewish Question” was a Jewish state, then what if that state had been established as a kind of national project of reparation and even retribution for the Holocaust? How would that shape its history and a politics and national character? I think I speculated out loud for a while—it’s that kind of marriage—and then my husband went to brush his teeth, returned, and said, “What about the Soviet Union?”

What about the Soviet Union? It existed. So did Stalin, who might have had his own plans for a Jewish homeland; he had created one called Birobidjan and slaughtered most of its inhabitants in purges. What about East Germany? It didn’t exist, or more precisely, this country would encompass much of its territory, though its borders, I decided, would be those of Saxony, east of Berlin. And yes, there’s a wall; it keeps out German fascists. The story begins in 1987. The wall is about to fall.

There is no single model for Judenstaat, though a reader will quickly find some parallels: two nations—Israel and East Germany — founded within a year and a half of each other. Both nations claimed to be a response to fascism, a way to move beyond tragedy and to rebuild ruined lives. Judenstaat borrows freely from the trajectory of both countries, with periods of post-war renewal, isolation, suppression, upheaval, and liberalization. A rough time-line appears at the end of this book. As a fortieth anniversary of my country approached, surely it would be time for a historical reckoning.

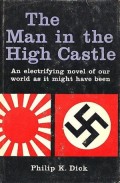

In constructing what follows, I couldn’t help but consider the nature of counter-histories, like Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, a novel that considers what would have happened had Germany and Japan won the Second World War, and goes beyond the thought-experiment and looked at the fragile nature of history itself. Then, I was led, inevitably, to Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-four, a vision of a future where the past can shift depending on who writes the story.

There is no answer to the Holocaust—or as they say in Yiddish, the Churban. There is no single answer to the Jewish Question. We keep on asking question after question. Perhaps the question that most shaped what you’re about to read is not national, but personal: What happens when you lose everything, but have to go on living? Who do you become?

We all know suffering is real. But in the end, all countries are imaginary.