By Liza Featherstone

Jacobin

Jenny Brown’s new book Without Apology: The Abortion Struggle Now, the latest in the Jacobin Series published by Verso, draws on decades of history and organizing experience to explain how we can win this fight over women’s reproductive labor.

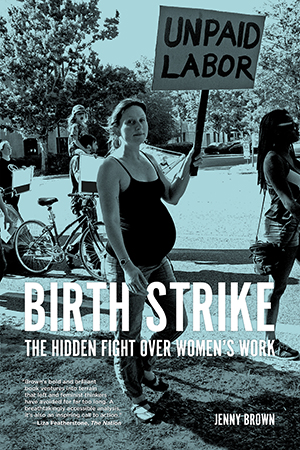

Brown, also author of Birth Strike (PM Press, 2019), has organized with National Women’s Liberation, Gainesville Women’s Liberation and Redstockings. She spoke with Jacobin’s Liza Featherstone at New York’s Strand Bookstore on October 10. A Kickstarter to raise funds for the launch of Without Apology can be found here.

LF

It’s conventional to ask an author, “How did this book come about?” Usually the answer is personal and individual. Your process is more collective than that, like lot of the feminist classics from the seventies, which came out of activism and consciousness-raising.JB

Yes, absolutely. The errors are all my own, but I tried to put into this book the experience and the theory, based on the experience of the last fifty years of fighting for abortion rights in the United States as well as some lessons from the recent Irish abortion struggle.

Living in Gainesville, Florida, I was recruited to Gainesville Women’s Liberation, which was reconstituting itself at the time. And one of the first things that we did was bring Lucinda Cisler, who is one of the theoreticians of the abortion movement from the sixties, to come and speak in Gainesville, and that led us to study the struggle.

And we were immediately able to put that to use because that was the year [1989] that the Webster Supreme Court decision came down, which was going to allow states to do more restrictions on abortion. And our governor, Bob Martinez, decided to call a special legislative session to restrict abortion in Florida. So, we immediately flew into action. People were saying, “Oh, let’s have a rally in, you know, a stadium in South Florida.” And we said, “No, we have to go where the special session is. We have to stop it.” So we had 10,000 people in the Capitol stopping it. It took a lot of organizing to get people to think of a militant action like that as the strategy that we should use.

But it was absolutely the correct strategy. We shut down the special session. Bob Martinez was defeated in the next election. That gave me a sense that these ideas that we were getting from the sixties movement are extremely powerful, and we can talk more about what some of those ideas were, but that just gave me a taste of we really can win.

And that the strategies that originally got us abortion rights are — we’re not trying them right now. We are backing down. We’re in a very defensive crouch right now. If we start adopting some of those strategies, I think we’ll make a lot more progress.

LF

We really, really need this! What are those ideas and strategies?JB

Many people who started the women’s liberation movement had been active in the Civil Rights Movement. In the Civil Rights Movement, people would get up and talk about the racist incidents in their lives. “Tell it like it is,” this was called. And so the women’s liberation movement adapted that into something called “consciousness raising,” where you’ll go around the room and people would talk about their lives, and compare their experiences and then figure out what was going on and who was benefiting. And one of the things that came up in early consciousness-raising was abortion. People for the first time talked to each other about their illegal abortions. So that was the first time that people started to see this as maybe a political thing, not just a personal burden to bear.

And in many ways, we are back to thinking of it as a personal burden to bear. The screaming picketers, the expense, having to travel to another state — all of these problems that we’re facing. What we get from consciousness-raising is that this is a specific strategy used by the power structure to oppress and exploit us. And so therefore it has a political solution and it’s not a personal private issue.

And then the other idea was, we had an abortion movement from the postwar period through the fifties and early sixties, professionals who saw the carnage that was caused by the abortion laws and the back-alley abortions. Their strategy was to make it easier for people who are in an extreme situation, cancer or fetal deformity or rape or incest, to get an abortion. That didn’t cover most people’s reasons for needing abortion.

And so when [feminists] did consciousness-raising, they became completely aware that this was not adequate to their needs. And that was why when [feminists] went to ask, “How do we do this politically?” they said, “Oh, well we’re not going to go for these reforms. They don’t cover most of us. They’re not going to unite us and we’re fighting for our own lives, what we want is repeal.” So it came directly out of consciousness-raising, that idea of repealing all the abortion laws.LF

And you were also a plaintiff in the successful lawsuit demanding the morning-after pill, right?

JB

Yeah, this was a ten-year struggle that went roughly 2003 to 2013. The morning-after pill, which works up to 120 hours after sex, but is most effective the sooner you take it, was available over the counter in thirty-seven countries, but not the United States. Here you had to go to a doctor, get a prescription, and go find a pharmacy that was open. It was sort of comical to think about, starting on a Friday night, how you would do this and how to be able to get the pill in time for it to be effective. So we were trying to make it available at the University of Florida where there were pharmacists who were blocking making it available to students.

And in the course of that struggle, an abortion provider at our local clinic said, “Well, you know, there’s really no safety reason to have it be a prescription drug. It should be available over the counter.” And we thought, “Huh!” But we were told by the nonprofits who were working on this stuff at the time, “Oh, getting it over the counter, that’s never going to happen. You need to do a winnable thing. Like, get it for rape victims in emergency rooms.”

So we took that back into our consciousness-raising groups and we said, “Okay, is this why we need the morning-after pill?” Most of us had not needed it because of rape. Those of us who had needed it because of rape had not gone to an emergency room. So we knew that that most people were not going to be interested in that as a struggle. And the way to unite people was to make a big demand that covers many people as possible. And that was: over the counter for all ages. So that was one lesson.

Another lesson that we got out of that struggle — all of these lessons were ones that we also got from the original abortion struggle — is to not go for half a loaf. Not to go for a compromise. And in the case of the morning-after pill, the compromise that we kept getting offered was, yeah, okay, you can have it for adults, but not if you’re under eighteen. Then later they said under seventeen. But we certainly had had experiences in our younger years of needing the morning-after pill.

What we talked about in consciousness-raising was how it was just when we were starting to have sex, when we didn’t have everything organized about how the contraception would work or insisting on the condom or whatever — that was the moment when it was really helpful to have the morning-after pill! So [the age limit] was the reverse of what we really needed. Able to get pregnant, able to decide: that was our position. So, the idea that you don’t cut off half of your base, half of the people who need what you’re trying to get. You don’t sell them out. That was very important in that struggle, too.LF

Another episode where all these lessons really come into bold relief is the recent victory in Ireland. Can you talk about what they did there and why it worked?JB

So, this was a referendum — I’m sure everybody was aware of it, in 2018 — to make abortion legal up to twelve weeks. In 1983, Ireland put it in the constitution that fetuses and women had equal right to life. So the Irish system regularly generated these horrifying cases: the fourteen year old who was raped and couldn’t get an abortion and needed three psychiatrists to say that she was suicidal.LF

And they had to be suicidal, right?JB

You needed two shrinks to say you were suicidal. And so [feminists] would fight for it to be, like, only one shrink saying you were suicidal, or [to extend abortion rights] if you had been raped. A lot of the movement was around trying to get little tiny reforms to the law, which really wouldn’t have helped most people.

By around 2012, 2013, this group of feminists — mostly anarchists in Dublin — got together and the first thing that they did that was kind of shocking to everybody, was they put abortion in the name of the group: Abortion Rights Campaign.

And then the next thing they did was, all these mobilizations that had been happening around these terrible cases, they just said, “Forget about all that. Let’s just have legal abortion in Ireland.” And that drew massive crowds. Every year they had demonstrations, and the number of people doubled every year.

[The referendum] won by 66 percent, which I think gives us some hope. I think a lot of people think that you are either on one side or the other of the abortion issue and you’re not movable. That was not true there. And I don’t think it’s true here. We have a lot of room for organizing people. And part of the way to organize them is not to just talk about these extreme cases, but to really talk about our own experiences.

We didn’t win abortion [in the United States] because all the professionals got together, we didn’t win abortion because the Supreme Court suddenly saw the light. We won abortion because people were in the streets demanding it — and actually demanding a lot more than we got with the Supreme Court decision. The women who planned and started the movement and made it happen are not in those history books. That’s a very effective thing; it makes us think that we don’t have the power to change things. We think all the change comes from the top.

But the Supreme Court had to grapple around to find some way to justify making abortion legal. They found it in the constitution, the same way that they found labor rights in the Commerce Clause. They found it because people were demanding it and they had to come up with some rationale.

I should say that the other thing that really helped in the 1960s in the abortion struggle was that most of the socialist countries already had legal abortion. You could go to Poland and get an abortion for $10. And you have to picture this, this was at a moment when the Cold War was essentially an argument about which type of system has more freedom: socialism or capitalism?

And here women were leaving the “free world” to go get an abortion in Poland for cheap. Right? That put a lot of pressure on the capitalist world. This looks really bad. Same thing with the Civil Rights Movement. It looked really bad that black people were being shot for wanting to vote in a democracy. Right? So then the federal government had to intervene, make it look better.

We don’t have that pressure right now. In fact, Poland is a great example. Poland, where you could go get an abortion for $10 — the moment they overthrew socialism, they went back to restricting abortion and now abortion is illegal throughout Poland. They punish doctors who provide them.LF

We got so much out of that superpower competition.JB

That we frankly did not realize at the time. West German workers used to say, when they were at the bargaining table, East Germany was also at the bargaining table.

LF

Why did the communists have better reproductive freedom, though? It’s not something many people know, because of authoritarian stereotypes about socialist and communist countries. Ceaușescu in Romania and Stalin, too, did ban abortion. But those were exceptions.JB

We have a hundred years of communist and capitalist systems to compare. The socialist world, pretty much every revolution, legalized abortion immediately. Even where it was hard to do, like Cuba. You had the Catholic Church there. Vietnam, Korea, and China, then the entire Eastern bloc. So, pretty much a majority of the world had abortion rights before the United States got them. Then after the United States got them, a lot of [Western] European countries did too. But clearly the socialist world led on this. These were people’s movements and they included women. And they needed women in the revolutionary movement to win.

They also saw women as more than just producers of babies. They saw them as comrades and soldiers and workers and teachers and leaders. The other thing is [communists] were willing to go up against the church. That was big. And then, capitalists are very concerned about growth and population is part of that growth. Socialists are not so concerned about that. They were more concerned about developing and then having the fruits of development be spread around.LF

Can you talk about what National Women’s Liberation is doing now and what are some of the ideas and politics behind that?JB

So, National Women’s Liberation has its roots in Redstockings, in those sixties radical movements, and we are trying to continue that tradition. We teach classes, we put out books, we put out information, but we’re also organizers. We’re hoping to create a study and action guide to go with this book.

It’s now easy to do a self-managed abortion, with pills. There are all kinds of regulations and restrictions around it. These are completely unnecessary. And why is it only doctors in most states who can provide abortions? This is a choke point that has been used against us — and Lucinda Cisler predicted that it would be. Some states have made it possible for other practitioners to provide abortions. They have just as good outcomes. It’s fine. So we need to make it so that anybody who’s a trained practitioner can provide an abortion. We need to not just try to keep these abortion bans from coming down the pike, but really expand our rights.

We also have done a lot of organizing around national health insurance. For example, the New York Health Act, which is basically statewide single payer. Everybody would be covered, and it includes abortion. Rather than this continual forty-year fight to get rid of the Hyde Amendment, which would still mean that you’d have to be on Medicaid to get your abortion funded — that leaves a whole lot of people out. What we really need is expanded, improved Medicare for all that covers abortion and birth control. We think that is the way to go. In fact, Redstockings pioneered this. In 1989 they changed their call for “free abortion on demand” to “free abortion on demand through a national health system.” We really need to win national health care.LF

And it’s a great time for that, right? In terms of the rest of the political landscape, with Democratic Socialists of America canvassing on this — and it’s a major plank of Bernie Sanders’s platform, including reproductive health care for all.

JB

You noticed after Bernie made this a big issue, all the other presidential candidates on the Democratic side have been saying that they’re for it, or sort of for it, and waffling back and forth. They’re definitely feeling the pressure because it’s so popular and people understand how it would work. But we should remember that when the Clinton health care reform was going through, they immediately jettisoned reproductive rights. They got rid of abortion, hoping that they could get support from Republicans.

And a group of black women [Loretta Ross and others] said, “jettisoning abortion is not going to get Republicans on your side on this.’ And that turned out to be true. They formed Women of African Descent for Reproductive Justice. They put an ad in the newspaper, signed by 900 black women, saying we are not going to support anything that doesn’t include the full spectrum of reproductive rights. And that was the beginning of the reproductive justice movement, which is, I’ll just give you the three principles: The right to have kids when you want to have kids, the right to not have kids when you don’t want to have kids, and the right to raise your kids under fair and decent conditions. They built a movement around this, led by the group Sistersong.

The New York Health Act would cover abortion for everybody in New York, because we have Medicaid coverage of abortion here and the act covers everything that Medicaid covers. I mean, we could still have a fight over it, but for now, this plan has everything.

About the Author

Jenny Brown is a member of National Women’s Liberation and a former editor at Labor Notes. She is a coauthor of the Redstockings book Women’s Liberation and National Health Care: Confronting the Myth of America and author of Birth Strike: The Hidden Fight Over Women’s Work. Her latest book is Without Apology: The Abortion Struggle Now.

About the Interviewer

Liza Featherstone is a staff writer for Jacobin, a freelance journalist, and the author of Selling Women Short: The Landmark Battle for Workers’ Rights at Wal-Mart.