By Jordan Larson

Bookforum

September-November 2019

As the earth melts, societies age, and economies slow, a narrative of humanity’s inevitable decline has settled in and calcified. It seems as though there’s no story left to tell but that of a slow descent into a gray future beset by any number of catastrophes. To hear pronatalists tell it, many of these will happen because we aren’t having enough babies. Fertility rates have hit an all-time low in the United States. For conservatives, this spells doom for all manner of American traditions: Social Security, masculinity, a robust economy, even democracy itself. New York Times columnist Ross Douthat has warned that low birth rates signify “a spirit that privileges the present over the future, chooses stagnation over innovation, prefers what already exists over what might be.”

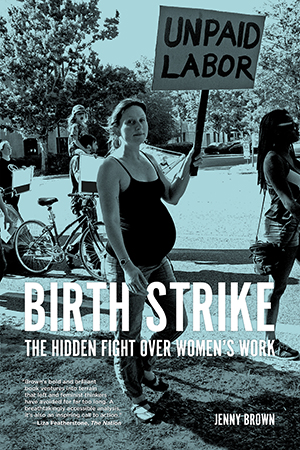

Could the so-called fertility crisis also be an opportunity for women to seize power? “Just as workers have found that bargaining power comes from uniting and refusing to work,” socialist feminist Jenny Brown writes in Birth Strike: The Hidden Fight over Women’s Work, “women’s bargaining power has increased when we have refused to produce children at desired rates.” Faced with wage stagnation, a lack of affordable childcare, and limited pregnancy leave, as well as the ballooning expenses of housing, health care, and college tuition, women are refusing to bear the costs of motherhood. Women suffer from a lack of real choice in whether and how to have children, but Brown frames declining birth rates as an assertion of agency: Women are mounting a birth strike, she argues, to protest abusive labor practices. “True,” she writes, the birth strike “wasn’t coordinated like a workplace strike and didn’t yet have a clear set of demands, but it’s still a slowdown in resistance to intolerable working conditions.”

An organizer with the feminist group National Women’s Liberation, Brown approaches her argument with the grounding of an activist. The book delivers an overarching account of population control and family policy and details the ways the US government has pushed the cost of reproduction onto parents. Birth Strike is especially adept at deflating panicked arguments over an impending baby bust. Against the conservative think tank alarmists who insist that Social Security will dry up and the economy will collapse, Brown argues that low birth rates really only pose a threat to corporate interests: Fewer babies means a smaller workforce, higher wages, and, to certain economists, slower economic growth.

The United States isn’t alone in its demographic panic. “Half of the world’s population now lives in countries where the birth rate is below replacement levels,” Brown writes, and policies in other countries show how much better things could be for parents—and how much worse they could get for everyone else. So far, fear of a demographic crisis has been harnessed primarily by conservative politicians: Erdoğan and Putin have explicitly linked their countries’ lagging birth rates with access to abortion and birth control. But Brown sees the potential for feminists to employ this rhetoric for their own purposes. Turning to the history of the European welfare state, she argues that twentieth-century social movements were able to translate similar fertility panics in countries such as France and Sweden into more robust pro-family policies: “Panic over low birth rates has led governments to underwrite childbearing and childrearing, providing paid maternal or parental leave, free or subsidized childcare, universal health care, cash payments to parents, plentiful sick leave, shorter workweeks, free schooling through college, and subsidies for housing,” Brown writes. Though higher birth rates would primarily benefit employers, Brown sees this desire as exploitable. If women organize effectively around collective demands and increase access to abortion and contraception to further limit the number of unintended births, the state may be forced to respond with policies that make parenthood more bearable.

Katrina Majkut, In Control 2, 2012, thread on aida cloth, 9 × 9″.

The United States has a long history of controlling women’s reproductive decisions in the name of managing the population, most egregiously with forced sterilization. Within the past eight years alone, more than four hundred abortion restrictions have been enacted across the country, and state legislatures have become more emboldened by Trump’s election and the confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court. In response, many liberal feminists have framed conservative efforts to restrict reproductive rights as religious zealotry and discomfort with women’s sexual autonomy.

But in Birth Strike, Brown argues that efforts to restrict reproductive freedom are less about cultural oppression than about controlling the birth rate and population size. “As long as we think of the battle over abortion and birth control as primarily a cultural conflict, in which the two sides simply hold different worldviews, it’s not clear why corporate owners and establishment planners would have much interest one way or the other,” she writes. “But if we look at the battle as a fight over the production of humans—how many, how fast, and at what cost—then it seems likely that employers, as a class, would have an intense interest.” To make her point she draws on the work of feminist historians, showing that abortion in the United States was virtually unrestricted until the mid-nineteenth century, when state legislatures began fretting about declining birth rates and increased immigration. By the 1880s abortion was banned in nearly every state and Comstock laws prohibited even the dissemination of any information on contraceptives.

The idea that abortion restrictions are really about birth rates, not religious fundamentalism, is persuasive, but Brown is too dismissive of the cultural factors at play. That the opposition to reproductive freedom is more materialist than cultural is frightening; what’s even more frightening (and insidious) is that it might be both. As Melinda Cooper argues in her groundbreaking book Family Values (2017), capitalism and social conservatism have long worked in tandem to restrict sexual freedom and enforce the patriarchal family. Stronger social-welfare policies that ease family life may seem like a valid trade-off for economic security. But even as its generosity waxes and wanes, welfare can always be deployed to limit non-normative sexuality, increase women’s dependence on the family, and surveil people of color. The lower birth rates fall, Brown argues, the more leverage women have to get the welfare policies they want. But if such policies were enacted explicitly in order to raise birth rates, wouldn’t they be structured in a way that limited women’s reproductive freedom?

Cooper is critical of Marxist feminists who see fertility as a bargaining chip, including Brown; in a recent academic paper, she warns that a potential childcare subsidization program enacted “on natalist rather than gender egalitarian grounds” would only make it harder for women to work outside the home, and runs the risk of being revoked if the state begins to fear overpopulation. While her warnings seem justified, it’s hard to see a way out of such an impasse: Would a robust childcare program fueled by pronatalist fears even be possible for many women to resist? After decades of struggle for even basic social support for mothers, and amid a rising obsession with birth rates—held by employers, politicians, and most overtly by white supremacists—is the feminist movement strong enough to reject any welfare program on offer?

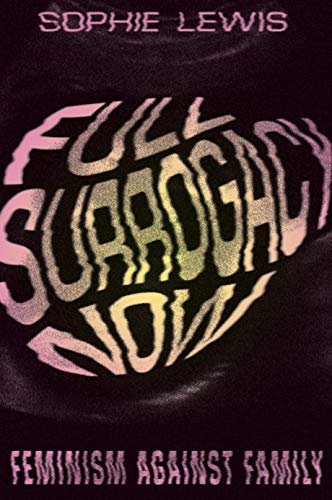

One attempt to reorient the labor of childbearing is the British academic Sophie Lewis’s speculative treatise Full Surrogacy Now: Feminism Against Family. For Lewis, the international surrogacy industry—in which wealthy clients pay poor women, predominantly in the Global South, to gestate their embryos—isn’t just evidence of neoliberalism’s inherent immorality. Instead, she sees radical potential to reimagine biological parenthood and the nuclear family. Lewis’s goal here isn’t quite as novel as it sounds: She calls to replace the isolated, rigidly structured family unit with communities in which adults share care responsibilities for all children, whether they are their “own” offspring or not. “Full surrogacy,” which Lewis defines as “sharing reciprocal mothering labors between many individuals and generations,” largely operates in the metaphorical sense.

Lewis makes two parallel arguments: that surrogates deserve greater autonomy, more rights, and higher wages; and that proprietary, biological parenthood must give way to a more diffuse, generous form of caretaking. While either argument is valid on its own, it’s sometimes difficult to see precisely how they relate to each other. Much of the book is given over to analyzing feminist opposition to the surrogacy industry and describing work conditions; multiple chapters detail the rhetoric and business practices of a prominent Indian surrogacy doctor. Lewis weaves theoretical digressions throughout, drawing a connection between surrogates and those who have babies for free by defining gestation itself as labor, whether it’s paid or not. However, what implications this observation has for a “gestational communism” future are unclear: It’s not hard to imagine how the burdensome labor of childcare might be better distributed, but how does one share the labor of pregnancy? Lewis stops short of calling for formalized surrogacy practices in private life. But the problems she identifies with the biological process of pregnancy aren’t quite answered by suggestions for family redefinition.

Still, Lewis’s call to decentralize the labor of gestation and mothering provides a compelling response to the overbearing pressure on women as individual arbiters of our collective fate. If buying into a narrative of demographic crisis makes women responsible for the production of the nation and of all social life, might viewing motherhood as the labor of communities, not merely individuals, begin to offer a way out? As the state attacks reproductive rights, makes a mockery of feminist values, and separates migrant families at the border, squinting at a utopian future of caretaking can seem merely inadequate at best and indulgent at worst. Lewis herself admits that such a societal arrangement could only develop in a postcapitalist world. But her work carves out a vital space for possibilities, fragile as they may be. In the meantime, as she writes, “it is a wonder we let fetuses inside us.”