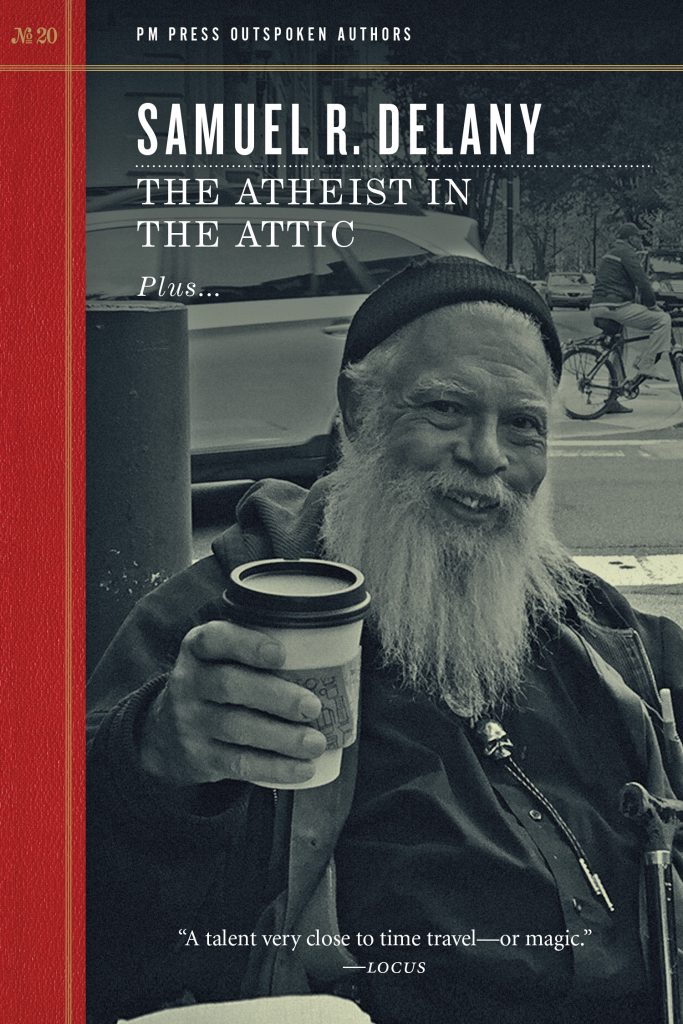

The author of “Dhalgren” and dozens of other books “gives readers fiction that reflects and explores the social truths of our world,” the novelist Jordy Rosenberg writes.

By Jordy Rosenberg

New York Times

August 8th, 2019

“In the long country cut with rain, somehow there was nowhere to begin.”

So reflects the nameless character, known only as “the Kid,” as he wanders an apocalyptic America in Samuel R. Delany’s science-fiction novel “Dhalgren.” A description of the book’s physical setting as well as the Kid’s fugue state, this sentence exemplifies what Delany has described as the task of fiction: achieving “resonance between an idea and a landscape.” It also happens to describe the vertiginous task of writing about Delany.

For there is, indeed, nowhere to begin with Delany. Born in Harlem in 1942, Delany published his first novel at the age of 19, inaugurating a broad, genre-spanning career that now includes over 40 published works and several major literary awards. His writing combines space opera with neo-slave narrative, memoir, sword-and-sorcery fantasy and an elegy for the sexual freedoms of pre-Giuliani Times Square. Delany’s prismatic output is among the most significant, immense and innovative in American letters. And because there is no way to summarize his work, about Delany we can never be experts. We can only be enthusiasts. We cannot hope to describe his oeuvre, only our encounter with his oeuvre, and how this encounter has transformed us.

“It is not that I have no past. Rather, it fragments on the terrible and vivid ephemera of now.”

Maybe it was that the Kid’s experience of loss resonated with my own. In 1992, when I was 21, my relationship with my family had been shattered by my queerness, and I had absconded to San Francisco for a girlfriend who dumped me upon arrival. In the aftermath, I found a job waiting tables on the overnight shift at Sparky’s Diner on Church Street in the Castro, and I found Delany.

Around 4:30 a.m., with the neon SPARKYS sign casting a pool of foggy pink onto the sidewalk — when the ravers had finished their French fries and tumbled off into the wet blue pre-dawn — I would crouch in the kitchen, reading “Dhalgren,” and later, the book that made me a Delany enthusiast for life, “Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand.”

“Have you ever arrived on a world at dawn?” asks that novel’s “industrial diplomat” and technology ambassador, Marq Dyeth. “You can see the world, this one orange and green with hydrocarbon soups, that one blue and white with oxidized hydrogen broths, another grit gray, still another dust brown, but all, whatever their dominant color, scythed away, as one circles, with night.”

This rhapsody on dawn as seen from space is delivered by Marq shortly after he is forcibly separated from his lover Rat Korga, a former slave and the sole survivor of a war-torn planet. At the hands of the General Intelligence — an agency that functions like a combination of OKCupid and the C.I.A., with even more invasive reams of personal information on the universe’s inhabitants — Korga is calculated to be Marq’s perfect erotic match and sent to him. They spend several glorious days together, but the G.I. deems their connection too dangerous, and Korga is deported.

“Stars” manages to connect the ethereal appeal of orbit with Marq’s yearning for Korga. “Desire isn’t appeased by its object, only irritated into something more than desire that can join with the stars to inform the chaotic heavens with sense,” he opines. “Fingers can’t point to anything anymore. And without such indications — oh, I still walk where I walked, look where I looked, but where I saw what once seemed wonderful, I see so little now — I feel so little.”

Delany’s books interweave science fiction with histories of race, sexuality and control. In so doing, he gives readers fiction that reflects and explores the social truths of our world. In fact, he traces the lineage of contemporary speculative fiction to Martin Delany’s “Blake; or the Huts of America,” a 19th-century novel about the escape from slavery and insurrectionary desires in Cuba and the Southern United States that is, as Samuel Delany argues in his seminal 1998 essay “Racism and Science Fiction,” “about as close to an sf-style alternate history novel as you can get.”

The lesson of “Stars” — one as intimidating and exciting to me now as when I first read it — is that desire, language and history are bound together, and that literature has the capacity to realize these connections, and, from them, to spin singular webs.

In Delany’s novels, desire and language are luminous silks, intensifying and refracting reality. His work thus becomes a paean to the experience of reading itself, which “Stars” makes palpable through ecstasies specific to sci-fi.

Before they are separated, Korga and Marq participate in a dragon hunt on the planet Vyalou. As they soar over a landscape “more mica than sand,” they learn that when dragon-hunting on Vyalou, one momentarily fuses consciousness with the creature in flight. “Fly! I flew,” Marq thinks. “Chills detonated my spine, my gills erupted rings of excitation, and I arched away, borne through the beat of other urges, to drop through the world built in my mouth, while Rat, at my shoulder, rose.”

The emotional dynamism of Delany’s sentences has been perhaps less acknowledged than his world-building, or the sweep of his vision. But when asked to speak about writing as a practice, Delany himself often turns to the art ofsentences, and of how to imbue words with such “ekphrastic force” that they summon the material presence of an imagined world. When Korga and Marq return to themselves they are awe-struck, struggling to narrate the intensity of their own transformative experience. It is impossible not to hear in that a metatextual echo of the obsession of Delany’s practice: that of creating the most immersive possible aesthetic experience for us, his readers and devoted enthusiasts.

“I was a dragon,” Korga wonders aloud. And then, struck with the impossibility of communicating the exquisiteness of having been a dragon in flight, Korga reaches for the most apt simile he can imagine. “I was a dragon? I was a dragon!” he cries. “It’s like reading.”

Samuel Delany: A Starter Kit

The Motion of Light in Water

Although one can begin anywhere with Delany, most readers will want to start with this memoir, chronicling his marriage to the poet Marilyn Hacker, his early career as a writer, and the bubbling sexual expansiveness of gay male culture in midcentury Manhattan.

Return to Nevèrÿon

Delany’s four-volume, very queer fantasy series repays the reader’s attention. The world he builds begins with a slave uprising and tracks the self-emancipated Gorgik the Liberator as he travels the countryside fomenting further rebellions. The third book, “Flight From Nevèrÿon,” contains the now-canonical story “The Tale of Plagues and Carnivals,” which tracks the outbreak of a plague closely paralleling the onset of the AIDS crisis in New York.

Dhalgren

The travels of an amnesiac drifter through a burnt-out, alternate-reality America. There may be no other novel of the 1970s, or since, that so profoundly captures the dire atmosphere of a nation in economic and political free fall, and the persistence of love and the survival of eros amid such total brutality.

Times Square Red, Times Square Blue

Two extended essays on the social space of Times Square as it has been transformed by waves of gentrification that routed the thriving gay male cultures congregating in its porn theaters. Taking inspiration from Pound’s “Cantos,”Delany poses the essays as “periploi”: contemporary versions of classical and medieval descriptions of coastlines, used as aids to early navigators. The “temporal coastline” of the midcentury 42nd Street/8th Avenue zone comes to life in Delany’s classic of queer history.

About Writing

Even if you aren’t a writer, you will be fascinated by Delany’s generous, indispensable collection of essays on the practice and theory of writing. He has pointed his erudition and imagination toward concrete advice on building sentences, using adjectives and structuring fictional works. The thoughtfulness of this effort makes clear how seriously Delany takes the reader’s experience of his texts, and how devoted he has been to confecting dreamworlds for us. “The fiction writer,” he says in a bit of advice that might describe his own oeuvre, “is trying to create a false memory with the force of history.”

Jordy Rosenberg is the author of the novel “Confessions of the Fox.” The Enthusiast is an occasional column dedicated to the books we love to read and reread.