By Martin O’Shaughnessy,

Nottingham Trent University

Anarchist Studies Journal 18.1 2010

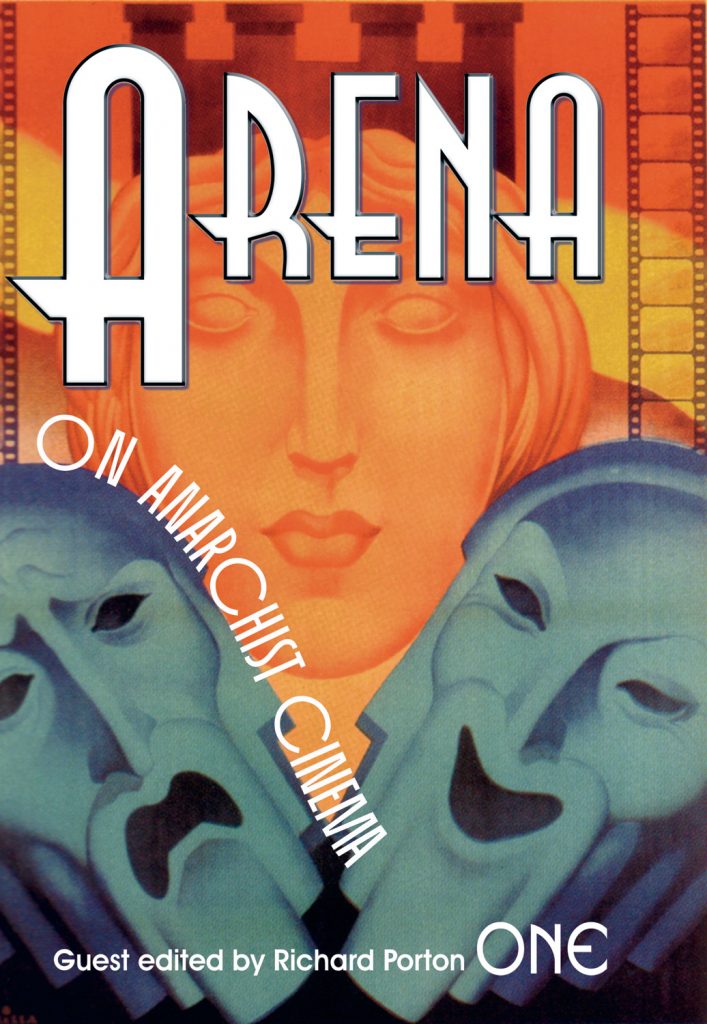

A promising-looking new publication for those interested in anarchism and culture, Arena presents itself as a journal that ‘will bring together stimulating writing and scholarship on all aspects of libertarian culture, arts, life and politics’.

The first number focuses on cinema and is edited by Richard Porton, author of the well known book Film and the Anarchist Imagination (Verso, 1999). Porton’s introduction begins by asking what we mean when we speak of an anarchist cinema. Are we referring to films about the historical experience of anarchism and anarchists, or would we broaden our definition to take in anti-authoritarian works made by non-anarchists? Porton’s own answer is to suggest that, despite a variety of styles and political origins, most ‘anarchist’ films promote self-emancipation and are inspired by the tradition of decentralised anarchist pedagogy.

The very diverse set of articles that follow might be seen as building on the thrust of this argument. Some engage with the largely neglected and inevitably discontinuous history of anarchist involvement in film, and use of film as political pedagogy: the short-lived Cinéma du Peuple co-operative that emerged in France in 1913-14; anarchist cinema during the Spanish Civil War from 1936 to 1939; the career of Armand Guerra, an important film-maker who linked these two periods; anarchist Gustave Cauvin’s pioneering development of educational film.

Other articles discuss the success or failure of films that set out to represent moments and figures in anarchist history: Theo Angelopoulos’s Alexander the Great(1980), William Keddell’s The Maintenance of Silence(1985), a film about New Zealander Ian Robert’s 1982 suicide-bombing of the national police computer data-base. A cluster of articles shift the focus to the present, looking at anarchist film festivals, the use of video recording to record police repression, and, more broadly, the diverse range of anarchist video in the new century.

Collectively, the pieces give a sense of the breadth and variety of anarchist cinema, and do important work by bringing neglected historical moments and marginalised practices into visibility. They also underscore how a rounded analysis of anarchist cinema needs to embrace both analysis of film form (notably the adequacy of formal choices to content) and political economy (the conditions of film production, distribution and exhibition). They are, however, uneven.

Emeterio Diez’s long piece on anarchist cinema in the Spanish Civil War is formidably well researched and packed with information, but needed more structure and a more developed analysis. Isabelle Marinoine’s piece on Cauvin could have explored his political evolution with a little more critical distance. Pieces by Russell Campbell and Dan Georgiakis on Keddell and Angelopoulos respectively carry out productive formal analysis;while Andrew Lee’s account of Vicente Aranda’s star- studded Libertariasrightly underscores the film’s superficial treatment of its subject, the anarchist feminists who fought in the Civil War. Andrew Hedden’s article on contemporary anarchist video is of considerable current relevance. By

developing an analysis of an e-mail survey carried out with over fifty self-identified individuals and groups involved in anarchist video production around the world, the article provides a fascinating account of how people reflect on their own film- making practice and the problems they face.

One telling section underscores the tendency of the image to be drawn to the spectacular dimension of demonstrations with a resultant neglect of less photogenic political activities. Overall, despite its unevenness, the journal issue provides productive ways to think about anarchist film-making. It will be interesting to see how the journal develops and how it deals with other areas of cultural production.