Shanta Nimbark Sacharoff (in pink scarf) works behind the counter at Other Avenues co-op in the Sunset District of S.F.

By Jonathan Kauffman

San Francisco Chronicle

March 16th, 2017

In the 1970s, the Bay Area developed a vibrant, interactive network of cooperatively run enterprises called the People’s Food System. Though it lasted only a few years, the movement gave birth to Other Avenues Food Co-op, Rainbow Grocery and Veritable Vegetable (now for-profit), all of which are still open. (Chronicle gardening columnist Pam Peirce started writing as one of the editors of the group’s newsletter.)

Shanta Nimbark Sacharoff, a longtime member of the worker collective at Other Avenues in the Sunset District, has told this story in her new book, “Other Avenues Are Possible” (PM Press, 2016, 200 pp., $14.95). The Chronicle asked Nimbark Sacharoff to outline the movement’s arc.

Q: Chronicle: How did the People’s Food System start?

A: Nimbark Sacharoff: The history of the People’s Food System was influenced by the 1960s era, when the war in Vietnam was ending and people still had the energy to remain organized. What better way to remain organized than to get together and share food, distribute food? At the time, the system wasn’t so much about making money or creating jobs but about food for the people — and we were the people.

We started with buying clubs. We called them “food conspiracies.” Food conspiracies were about education and outreach to the whole community, using food distribution as a vehicle for social change.

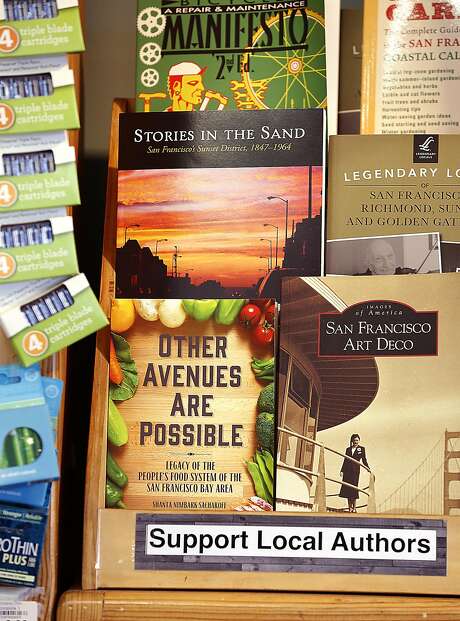

Photo: Liz Hafalia, The Chronicle Shanta Nimbark Sacharoff’s book “Other Avenues Are Possible” is a history book about Bay Area food co-ops and food-buying clubs in the 1970s.

Q: What was involved in a food conspiracy?

A: Typically, you’d get together with neighborhood people and sign up for the foods you want. The person who was hosting the ordering was also hosting a potluck dinner. He or she would provide the space, and you’d come and bring your money or food stamps, and that list would get compiled, and the food buying would be on Saturday or Sunday. Once a month was the “Great Divide,” when we divided up dried food.

Q: How many food conspiracies were there?

A: There were hundreds of conspiracies in San Francisco, concentrated in (the western half) of the city, the Mission and Noe Valley. In the Haight, the motto was “If you can’t walk to order food, you should start a new food conspiracy.”

Q: How did they turn into stores?

A: In the mid-1970s, we were moving lots and lots of food — probably hundreds of thousands of dollars of food, all combined. We thought not only would it be safer and cleaner if we opened up stores, we could reach more people. In 1974 the first store opened, the Noe Valley Food Store. Before that there was one called Seeds of Life, Semillas de la Vida, in the Mission.

More on Co-ops

Q: At its peak, how many businesses were in the People’s Food System?

A: Approximately a dozen storefronts. The biggest ones were the San Francisco Cooperative Warehouse, they did all the dry goods, and Veritable Vegetable, now a thriving national organic business. There was a big herb collective and a cheese collective. There was a one-woman milk business. There was a poultry place where we got eggs, and a Honey Sandwich co-op nursery school.

Ed. note: The People’s Food System fell apart in 1977 and 1978 due to political infighting and a turf war between two groups of former prisoners that ended in a shootout outside the warehouse. You can read Nimbark Sacharoff’s book for details.

Q: How did Other Avenues survive the collapse of the People’s Food System?

A: It was really difficult, especially for a small store like this. We had 10 years that were so difficult financially and organizationally — we almost closed down three times — but the community was our strength. Because we’re so isolated, the community that lives near us is drawn to us.

Jonathan Kauffman is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: [email protected] Twitter: @jonkauffman