Our Stories Can Take the Bastards Down

An interview with Sin Soracco and Patrick Marks, proprietor of The Green Arcade

PM: Low Bite was written in the 1980s. Why reprint it?

SS: This is your whack idea. What goes along with why you wanted to print this, in my mind, is you had the good sense, so far as we are all concerned, to choose The Green Arcade imprint not to be just some prissy-assed ecology stuff that everybody will get sick of — that’s valuable, ecology, it’s one of the pushes of the store — but we are talking about something else we love here, and what we love is trash crime. And trash crime that maybe is a little more crazed, with more going on than in the hard-assed noir genre with all the standard twists. What you managed to do by digging up this weird little cult volume was to find an old example of bad-girl trash crime. At the time it was done there were no female writers doing noir. Leigh Bracket was gone. Dorothy Hughes was way gone.

Dorothy Hughes

was reprinted by The Feminist Press and there are people who are trying

to retrieve a lot of those books. And I feel I have to add that The

Green Arcade imprint will publish books on ecology — and also on what I

call “green”: the built environment, food, culture, justice, and also

writing about cities. And those — rebels and fl aneurs, poets and

architects — who build, inhabit, and add something valuable to the

places I love. One of the reasons that I wanted to retrieve you was

because part of my idea of The Green Arcade, beyond what my idea of what

“green” might be, is also the idea of the “arcade,” and the

arcade has to do with the multiplicities of space in the city —

The Arcades Project is one of the books on my side of the bed.

Walter Benjamin is one of the store mascots, along with Rebecca Solnit. So it has to do with starting right where you are, on Market Street, in San Francisco. And part of the thing about SanFrancisco, to me, is you, Sin Soracco. And here we are doing this interview at the Russian River. But the Russian River has been a big extension of San Francisco, San Francisco the Imperial City.

The river can be looked at as an extension of the City because it would not exist as it is at all without having had a functioning working class nearby. The redwoods right here in our backyard were logged to rebuild San Francisco after the 1906 quake. The City is the place, whether we like it or not, which infuses its aesthetic on the world. There’s remarkably cool shit in the City. And that impacts the way that we look at the world and what we decide is important and beautiful and worth treasuring. Low Bite doesn’t take place in San Francisco but was written in San Francisco. And even so a lot of the not-apparent stuff in the book was supported by the life I was living in San Francisco, that let me go work in the stupid-ass bookstore, come home, get loaded, or be loaded already, and sit down and tell stories. So this idea of telling stories is at the basis of your … mission?

Don’t really have a mission. But I really believe that our stories can take the bastards down. I like to put it that way because it is fundamental to any art form to challenge the prevailing social and cultural things that are happening. On the other hand, you don’t survive, as an artist, unless you have rich people supporting you. Or, contradicting that, unless you have a lunatic like Patrick at The Green Arcade who wants to publish what he wants to publish. He is not a San Francisco socialite with a trust fund who is able to patronize.

I am too a socialist! Let’s go back and talk about when you first started Low Bite and from where it sprang.

Okay. I am an ex-convict. I did years in California prisons and jails and I found it to be really just an extension of the kind of life that I was living.

You found the inside to be an extension of the life that you lived on the outside?

Yes,

very much so. The diff erence, mainly, was that inside you had less

choice. But cultural norms — depending on where you live in the City —

it could be a little more ghetto than other parts of the City, but, in

other ways, the attitudes, the demand for respect, the sly trying to get

over, the forms of honor and friendship, the game you play for

survival, the insubordinate life: the same. The main problem is you’re

fucking locked up! You’re locked up and that sucks! And it’s dead

boring, it really is. But it was, at the time, not utterly foreign, at

all. Then I was back on the street, and sort of getting over my

jailhouse

self — we did what we did in jail — tell each other

stories, lies and otherwise. And the hilarious ones were of crimes gone

wrong.

I think that one the great things about Low Bite is the humor and how it is used against the insanity and against —

Authority. The other day I was reading some recent political crap, and it’s the same as it ever was, but what I got was that the American system is founded on the abuse of power. If somebody has more money, if somebody has a position that is above somebody else, if they have money enough to buy and sell somebody else, they’re going to do so, they’re going to abuse that position. Every time. Down the line. Because they can. The American system is set up so that those in power can abuse it. Everybody knows that, except apparently they don’t. [Laughs] In terms of writing a book set in a woman’s prison, there were things that I wanted to use that world for. I tried very hard not to be overtly political —

It is, in fact, an extremely political book.

But I don’t want anyone to know that. I want to, hopefully, change the way they look at the world or at least while they’re reading it, they go, “Ah.” The fi rst draft, the fi rst 60 pages, I handed to one of my friends from jail, and she said she had to lay down when she was done and put a cold rag on her head. Because it was too real and she said, “You know, hon’, we had a lot of fun. We made it a point to have a lot of fun, and you are ranting and raving here, just puking horror on the page.” And I realized that if I insisted on writing that book, nobody but a real psychotic would want to read it. What I wanted to do was to bring people to jail and I wanted them to stay there long enough to read the goddamned book. If I did what I did originally, puke all over the page, nobody would have read it.

I think you were successful in bringing us into the jail. And keeping us there for the duration. And we actually had a good time with all those women. I’m tempted to say that it was a riot, but that might be a spoiler. But the system sucks, you get that.

I figured that one out every five people is gonna end up in jail and virtually everybody knows someone in jail. And it would be very nice if people got a clue as to what the American system does. And I don’t even go into the horrific places like Pelican Bay, or some of the women’s joints that are rougher, in terms of the physical situation, than the ones that I was in. And I think that it would be very diffi cult to get someone to spend an hour in Pelican Bay, or Florence, or Angola, or Lexington Women’s joint that closed in ’88. These max units are far more horrific than the ones that I was in. I think that it would be very difficult to get someone to spend an hour in Pelican Bay if they could simply close the book and just leave. I want to tell a story. I want people to get a clue about a world I am intimately familiar with and they are not. Virtually everything I write I choose to set in a world that is absolutely normal to me that a lot of people who chose to read English-language literature are unfamiliar with.

That probably goes for the publishing world as well. And most booksellers.

I was in New York City on a dance tour —

— Another story —

— and I stopped off , because they were working on the paperback of Low Bite, and I walked into this huge multistory publishing house and realized that there was not a single person out of the hundreds of little people running around the rat-maze in their little Diane Feinstein outfits who physically looked or moved like I did. And here I am writing the fodder for this whole machine. They all looked at me like I was a loon. I did adore my editor, but people would ask me, “Wherever did you get your ideas for your characters?” And I would say, “These are bits and pieces of my friends. Even the villains. I’ve taken people I love and used their gestures and added that to a make a villain. Every part of every character in every book I write is somebody I generally know and love. Except for the very oddest villains who are — you people!” [Laughs] There have been a number of times in my life that I have walked into some place, the publishing world for sure, and it’s “Oh my god, I really don’t belong here.” It’s like the dope smoker who walks into a room of straight people and asks, “What should I do with my face? How do I behave in here?” But one of the things I want to get at is the unbalance of power, and how we can undermine that. How we in fact live well. In spite of everything.

The character Morgan in Low Bite ends up doing rather well. Many of the women in the book are doing rather well.

That’s the reason the last line of the book is “How sweet it is.”

I wanted to ask you about noir.

When I wrote this, I submitted it, and several people read it. I won’t go into a very famous literary agent who turned it down, saying, “You write beautifully, but if this were from a guard’s perspective…” I wrote a fl aming letter back. There is still some creepy acrimony behind that. On the other hand, the people who read it and liked it said, “Oh my God, we are looking for noir fi ction, you are one the few women today who are writing noir fi ction.” I said, “Oh! Ah, what’s noir?” I wrote what I wrote because that’s the way I see the world. I did not know anything, including the noir movies. I’ve never studied literature or taken a class in writing.

I’m not sure that academia is necessary to storytelling. There were tales that black women, Latino women would tell, their stories, in the joint, and I’m sitting there going, “This is great, this is marvelous. You need to write this down.” And they go, “I can’t write.” And I say, “It doesn’t matter, get this down. Anybody can learn to write proper cash English — but not anybody has wonderful stories. Get this shit on paper, man! Your spelling and grammar can be cleaned up — you don’t want to write cash English anyway. It’s not fun to read. It’s the stories that matter.”

After the book came out, people would come up to me and say: “So, you write noir.” I would say, “Yeah, um, sure.” And I’m thinking,“what’s that?” I didn’t know. There’s no reason I should have known. There were books I liked, but really until I started to work in bookstores — I worked in a little bookstore, then I went to jail. And then I got out. And I got a job at Books Inc. in San Francisco where I met you, Patrick, and Alison Moxley and Margie Burke. Booksellers! Because I was such a hard-ass, no-one knew I was a cultural dud. I didn’t know anything about anything, except for crime. And then I was fortunate enough to work at City Lights. I now have a fairly standard understanding of literature. But at the time I wrote this — not much.

Low Bite was first published by Barry Giff ord under his Black Lizard imprint.* How did you find Barry?

Paul Yamazaki from City Lights. After I got the rejection letter from the famous lady telling me about writing the book from a guard’s point of view, I absolutely burst into fl ames and I wrote a letter back, which apparently burst into fl ames on her desk! Yamazaki said, “Black Lizard.”

Black Lizard was still pretty recent then, right?

They had a few titles out. Paul submitted it to them and they took it in about a week. And, oh: Low Bite — and Edge City [Sin’s second novel] and the story “Double Espresso” in Peter Maravelis’s San Francisco Noir — have never been edited. Copyedited, yes. Black Lizard did have a wonderful copy editor, who caught two things. What Barry told me with Low Bite was: “We don’t have time to do any of that. You get the fame, you get the blame.” Later on at Penguin, they sent Edge City to a copy editor; she didn’t like the book at all and she was tagging the thing with post-its. I have two of my bad girls on the street at night in North Beach and they remark how much like Dante’s Inferno it is. Post-it: “I don’t think girls like this would know Dante’s Inferno.” If anyone knows Dante’s Inferno, it’s people who have been in jail: it’s convicts, it’s ex-convicts, it’s people on the street — they know Dante’s Inferno. However, both books could have profi ted from a real editor. Nobody really put their hands on it.

But that is what I like so much about this book, that it is in the form you wrote it, and we have left it, and it is even more of an artifact. Telling the story is the thing. I wanted to ask you: How has prison changed since Low Bite was written in the ’80s?

Twenty years ago the health system sucked. It has, over those twenty years, with tuberculosis, Hep C, and HIV, become absolutely horrific. And that is not going to improve in California because the state is in a state of total collapse. So the people who are going to get hurt are the least of us. Now, for one my favorite soapbox moments: there are perhaps five percent of the people in prison who ought to be there. The other ninety-fi ve percent, by and large, are assholes but they shouldn’t necessarily be in prison. Now which is the fi ve percent? I am an asshole, so I will answer: they are the people I don’t like. They should never get out of prison, these people I don’t like. When you think about it, what the parole board does, what the judges do — the people they send to jail, the people they keep in jail, are people they don’t like. So, I have my own list. Anyone who tortures — gee, there goes the U.S. government — anyone who is cruel to animals or children. Mostly cruelty is the thing. Now, most of the murderers that I’ve known, many of them were not criminals. Many of them killed and would probably not kill again, unless of course the situation called for it. But of heinous crimes there is this weird idea that taking another human’s life is the ultimate bad thing to do. But I think the worst crime is horrific domination. Cruelty. Greed. Which goes back to my basic political feeling that America is based on abuse of power. And this is what I feel is most unforgivable. So, if things have changed at all, they have changed for the worse.

Low Bite has a certain story to tell today which is every bit as grabbing as it was twenty years ago.

Hopefully. Or as topical. It was a cult favorite. There were groups of odd people. I had one group of little old ladies who really liked it. One of them was a lovely, very delicate woman who came up to me later and said, “My only problem is,” — she was a Jungian therapist — “I did not get a feeling of redemption at the end.” And I said the redemption is choosing to live the way they want to in spite of everything. The insubordinate lifestyle. At the end of the book, they are all kicking, they are going along. They are all doing fine. And given the way the world is, I could not see any greater redemption.

Your redemption is throughout the book, it is ongoing.

She wanted something at the end. But what noir does excellently is that it leaves the story rumbling after that last page. I hate the classic mystery where all of the loose ends are tied up — unless they are very good. It is more fun to allow it to reverberate forward through time. And you, Patrick, have rescued the goddamned book — you have demanded that it will reverberate forward through time. [Laughs]

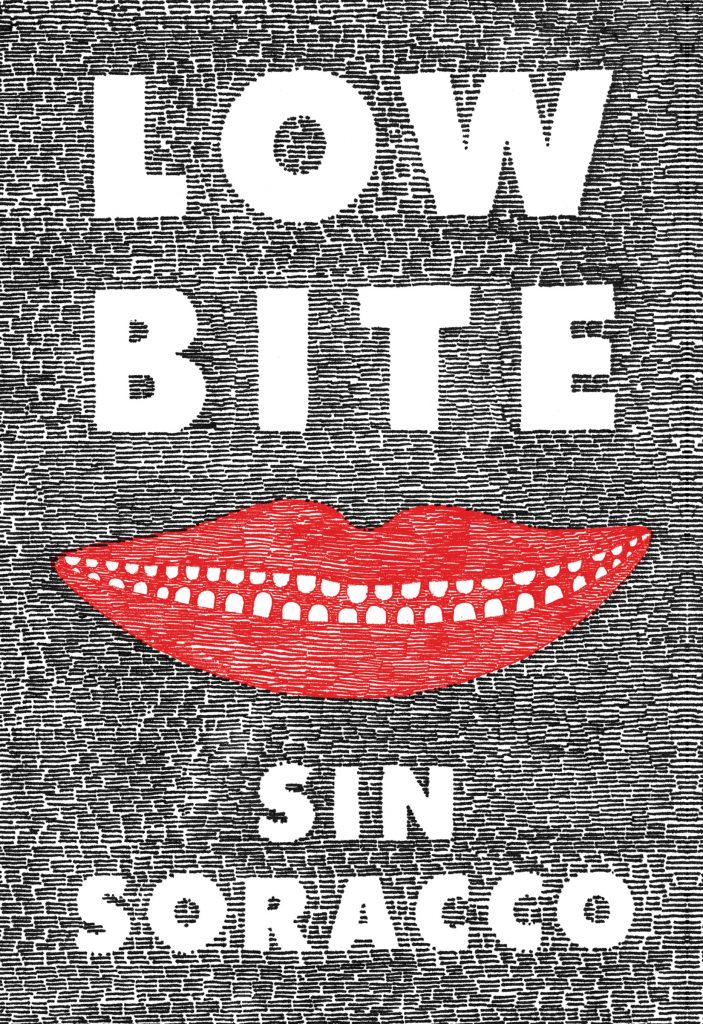

Do you want to talk about the cover of this new edition?

I am so excited, so pleased about the cover. It is jailhouse, without Gent [Sturgeon] having even spent time in jail! The obsession of the hand-drawn background of the bricks: this is what we do in there; and if you see jailhouse art, there’s a tattooish quality, there’s a graffiti quality, there’s an untrained-artist quality. But what there is under all of it is that emotional kick to the gut. There is an intensity that says, “This is what I am doing. It is worth something. This is worth people paying attention to, even if all I seem to be doing is cross-hatching.”

And that relates to the same message behind story telling.

I have something important to say: Finding a venue where I get the respect and the love and the support to say it, is rare and wonderful and needs to be cultivated. There we go! PM Press. The Green Arcade. Gent Sturgeon. Patrick Marks.

Isn’t it a bit of a contradiction to want to live well and yet to be always in opposition to the outside, or the inside, and always against something?

But it is oppositional. For those of us who come from outlaw stock and that tradition there is a conscious decision, a responsibility to oppose what goes on and what is acceptable in the traditional balance of power. And I live in opposition to the traditional balance of power in most everything that I do. And the responsibility, further, is that we live well.