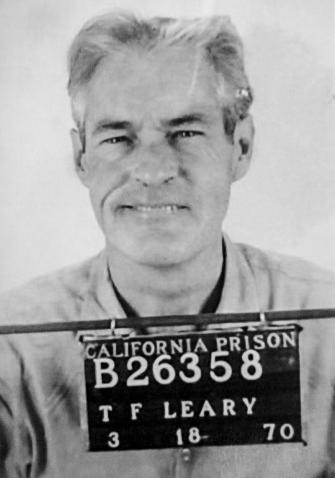

Dying to Know: Ram Dass & Timothy Leary is a unique

documentary that serves as an important slice of countercultural

history. Peppered with poignant wit, it inspires boomers and millennials

alike. I’ve been truly fortunate to have this pair of psychedelic gurus

as intimate friends.

By Paul Krassner,

originally published on EatDrinkFilms.com

In 1964, I assigned Robert Anton Wilson to write a front-cover article in The Realist, which he titled “Timothy Leary and His Psychological H-Bomb.” When that issue was published, Leary invited me to visit the Castalia Foundation, his borrowed estate in Millbrook, New York.

The name Castalia came from The Glass Bead Game by Herman Hesse, and indeed, the game metaphor permeated our conversation. Leary talked about the way people are always trying to get you onto their game boards. He discussed the biochemical process “imprinting” with the same passion that he claimed he didn’t believe anything he was saying, but somehow I managed to believe him when he told me that I had an honest mind.

“I have to admit,” I said, “that my ego can’t help but respond to your observation.”

“Listen,” he assured me, “anybody who tells you he’s transcended his ego….”

Leary and his research partner, Ram Dass (then Richard Alpert) were about to do a lecture series on the West Coast. At the University of California in Berkeley, there was an official announcement that the distribution only of “informative” literature (as opposed to “persuasive” literature) would be permitted on campus, giving rise to the Free Speech Movement, with thousands of students protesting the ban in the face of police billy clubs.

Leary argued that such demonstrations played right onto the game boards of the administration and the police alike, and that the students could shake up the establishment much more if they would just stay in their rooms and change their nervous systems. But it wasn’t really a case of either-or. You could protest and explore your 13-billion-cell mind simultaneously.

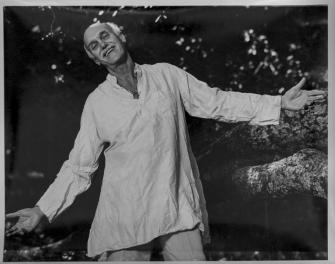

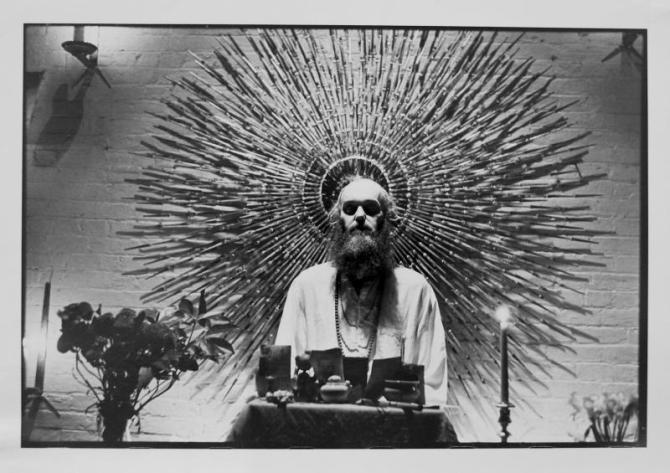

I became intrigued by the playful and subtle patterns of awareness that Leary and Alpert manifested. If their brains had been so damaged, as mythologized by mainstream media, how come their perceptions were so sharp? I began to research the LSD phenomenon, and in April 1965 I returned to Millbrook for my first acid experience. Tim Leary was supposed to be my guide, but he had gone off to India.

Dick Alpert was supposed to take his place, but he was too involved in getting ready to open at the Village Vanguard as a comedian-philosopher. I chatted with him for a while. He was soaking his body in a bathtub, preparing his psyche for the Vanguard gig. He had taken 300 acid trips, but there I was, a first-timer, standing in the open doorway, reversing roles and comforting him in his anxiety about entering show business. When I told my mother about taking LSD, she was quite concerned. She warned me, “It could lead to marijuana.” And she was right. It did.

After Leary got arrested in Texas for possession of pot, the notoriety of his research in Millbrook spread. Law enforcement in nearby Poughkeepsie, led by Assistant District Attorney G. Gordon Liddy, raided the estate. In the summer of 1966, Leary and his associates ran a two-week seminar on consciousness expansion, culminating in a theatrical production of Hesse’s Steppenwolf legend that weaved its way around the Millbrook grounds and buildings. Leary invited Liddy and members of the grand jury that indicted him, but none showed up.

Leary told me about prominent people whose lives had been changed by taking LSD: actor Cary Grant, director Otto Preminger, think-tanker Herman Kahn, Alcoholics Anonymous founder Bill Wilson, Time magazine publishers Henry and Clare Boothe Luce. Of course, it wasn’t so difficult to drop out when you had such a stimulating scene to drop into. On the day that he announced the formation of a new religion, the League for Spiritual Discovery (LSD), I signed up as their first heretic.

Alpert and I enjoyed what he called “upleveling” each other with honesty. On one occasion, we were at a party. I was particularly manic and he pointed it out, choosing an eggbeater as his analogy. I appreciated his reflection and calmed down.

On stage at the Village Theater, Alpert was sitting in the lotus position on a cushion, talking about his mother dying and how there seemed to be a conspiracy on the part of relatives and hospital personnel alike to deny her the realization of that possibility. He also talked about some fellow in a mental institution who thought he was Jesus Christ. Conversely, I teased him about discussing his mother openly but concealing the fact that the man who thought he was Christ was his brother–death obviously carrying more respectability than craziness. At his next performance, Alpert identified the man as his brother.The essential difference between Tim Leary and G. Gordon Liddy was that Leary wanted people to use LSD as a vehicle for expanding consciousness, whereas Liddy wanted to put LSD on the steering wheel of columnist Jack Anderson’s car, thereby making a political assassination look like an automobile accident. But who could have predicted that, sixteen years after the original arrest, Leary would end up traveling around with Liddy in a series of debates?

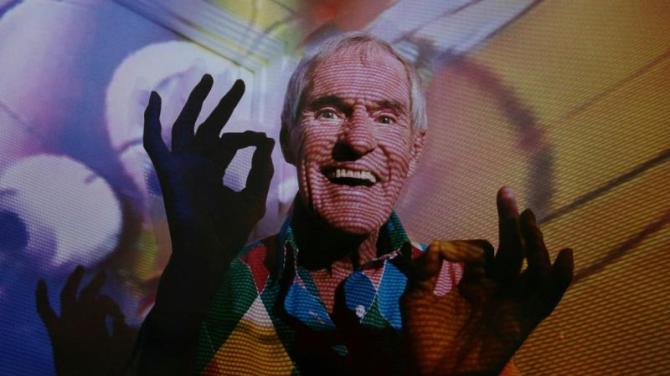

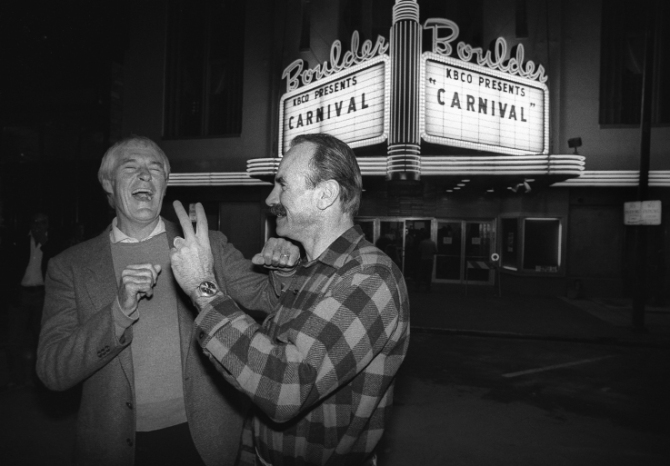

I attended the debate in Berkeley in April 1982. Leary warned the audience that Liddy was a lawyer—“trained in the adversary process, not to seek truth. I was trained as a scientist—looking for truth, delighted to be proved wrong.” He confessed that “Liddy is the Moriarty to my Sherlock Holmes—the adversary I always wanted—he is the Darth Vader to my Mr. Spock.”

“As long as it’s not Doctor Spock,” said Liddy. He argued that “the rights of the state transcend those of the individual.” Not that he was without compassion. “I feel sorry,” he admitted, “for anybody who uses drugs for aphrodisiacal purposes.”

Credit: David Bjorkman/Zone 913 Photo Agency/mytowncolorado.com.

“Gordon doesn’t know anything about drugs,” countered Leary. “It’s probably his only weakness.” He looked directly at Liddy. “It’s my duty to turn you on,” he said, “and I’m gonna do it before these debates are over.” Then he made a unique offer: “I’ll eat a rat if you’ll eat a hashish cookie.”

Liddy turned down the offer—one can carry machismo only so far, and he had to draw the line somewhere—but he did provide appropriate grist for my own stand-up comedy mill. According to Liddy’s book, he actually ate a rat. He did it to overcome his fear of eating rats. Certainly a direct approach to the problem. None of that gestalt shit. Now, I’m not sure how he ate the rat, whether he just stuck it between a couple of slices of bread, or barbecued it first, or chopped the rat up and mixed it with vegetables in a stew.

But there were rumors that when Leary and Liddy were on tour, the Psychedelic Liberation Front found out their itinerary and began feeding hash brownies to rats and releasing them, one by one, in Liddy’s room at the various motels he stayed at, while he was debating, in the hope that nature would sooner or later take its course, and one night Liddy would feel in the mood for a midnight snack, catch the rat that was left in the room, eat it and, by extension, the hash brownie the rat had eaten, and then Liddy would think he got stoned from eating the rat. This would, of course, be right on the borderline on the ethics of dosing.

Each tablet of Owsley White Lightning contained 300 micrograms of LSD. I had purchased a large enough supply from Alpert to finance his trip to India. The day before he left to meditate for six months, we sat in a restaurant discussing the concept of choiceless awareness while trying to decide what to order on the menu.

In India, he gave his guru three tablets, and apparently nothing happened. Alpert’s postcard to me beckoned, “Come fuck the universe with me.” Instead, I stayed tripping in America, where I kept my entire stash of acid in a bank vault deposit box.

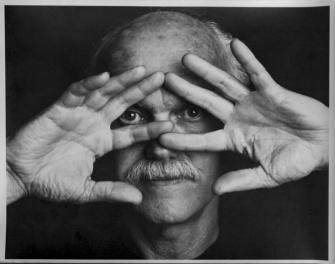

Richard Alpert returned as Baba Ram Dass. Eventually, he dropped the Baba. He was now just plain Ram Dass. His father called him Rum Dum. His brother called him Rammed Ass. One afternoon he was visiting me, and I taped our conversation.

“In 1963,” I said, “I predicted as a joke that Tiny Tim would get married on the Johnny Carson show, and in 1969 it happened. You and I talked about that, and you called it ‘astral humor,’ but I never knew exactly what you meant by that phrase.”

“Well, it’s like each plane of reality is in a sense a manifestation of a plane prior to it, and you can almost see it like layers, although to think of it in space is a fallacy because it’s all the same space, but you could think of it that way. And so there are beings on upper planes who are instruments of the law. I talk about miracles a lot, but I don’t live in the world of miracles, because they’re not miracles to me. I’m just dealing with the humor of the miracle concept from within the plane where it seems like a miracle, which is merely because of our very narrow concept of how the universe works.”

Ram Dass knew of my involvement with conspiracy theory. “I’m just involved in a much greater conspiracy,” he continued. “You can’t grasp the size of the conspiracy I understand—but there’s no conspirator—it’s the wrong word. That’s why I say it’s just natural law. It is all perfect.”

“Would you agree with the concept [of] what William Blake said, that humans were created ‘for joy and woe’—the implication of which is that there will always be suffering?”

“I think that suffering is part of man’s condition, and that’s what the incarnation is about, and that’s what the human plane is.”

And I asked Ram Dass, “If you and I were to exchange philosophies—if I believed in reincarnation and you didn’t—how do you think our behavior would change?”

He paused for a moment. “Well,” he said, “if you believed in reincarnation, you would never ask a question like that.” And then his low chuckle of amusement and surprise blossomed into an uproarious belly laugh of delight and triumph as he savored the implications of his own Zen answer. I would find myself playing that segment of the tape with his bell-shaped spasm of laughter over and over again, like a favorite piece of music.

Dying to Know: Ram Dass and Timothy Leary

Opens Friday, July 10, 2015 at Roxie Theater in San Francisco, Rialto Cinemas Elmwood in Berkeley, Rialto Cinemas Sebastopol in Sebastopol, and Christopher B. Smith Rafael Film Center in San Rafael. dyingtoknowmovie.com.

Paul Krassner calls himself an investigative satirist. Don Imus labeled him “one of the comic geniuses of the 20th century.” And, according to the Los Angeles Reader, “Krassner delivers 90 minutes of the funniest, most intelligent social and political commentary in town.”

On the other hand, a couple of FBI agents went to one of his performances and stated in their report, “He purported to be humorous about government policies.” His FBI files indicate that after Life magazine published a favorable profile of him, the FBI sent a poison-pen letter to the editor, complaining: “To classify Krassner as a social rebel is far too cute. He’s a nut, a raving, unconfined nut.”

“The FBI was right,” says George Carlin. “This man is dangerous—and funny; and necessary.”

ABC newscaster Harry Reasoner wrote in his memoirs, “Krassner not only attacks establishment values; he attacks decency in general.” So Krassner named his one-person show Attacking Decency in General, receiving awards from the LA Weekly and DramaLogue. He is the only person in the world ever to win awards from both Playboy (for satire) and the Feminist Party Media Workshop (for journalism).

When People magazine called Krassner “Father of the Underground Press,” he immediately demanded a paternity test. Actually, he had published The Realist magazine from 1958 to 1974. He reincarnated it as a newsletter in 1985. “The taboos may have changed,” he wrote, “but irreverence is still our only sacred cow.” The final issue was published in spring 2001.

His style of personal journalism constantly blurred the line between observer and participant. He interviewed a doctor who performed abortions when it was illegal; Krassner then ran an underground abortion referral service. He covered the antiwar movement; then co-founded the Yippies with Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin (writing a few animated re-enactment scenes for the documentary Chicago 10 four decades later). He published material on the psychedelic revolution; then took LSD with Tim Leary, Ram Dass and Ken Kesey, later accompanying Groucho Marx on his first acid trip.

He edited Lenny Bruce’s autobiography, How to Talk Dirty and Influence People, and with Lenny’s encouragement, became a stand-up comic himself, opening at the Village Gate in New York in 1961. Ten years later—five years after Lenny’s death—Groucho said, “I predict that in time Paul Krassner will wind up as the only live Lenny Bruce.” He was nominated for a 2005 Grammy Award in the Album Notes category for his 5,000-word essay accompanying a 6-CD package, Lenny Bruce: Let the Buyer Beware. Krassner rarely works the comedy-club circuit, preferring to perform on campuses, at theaters and in art galleries.

He has been a guest on Late Night with Conan O’Brien and Politically Incorrect with Bill Maher; on Air America Radio with Janeane Garofalo and on WTF with Marc Maron. He hosted his own radio call-in show in San Francisco.

Paul is an occasional contributor to the Huffington Post. His articles have appeared in Rolling Stone, Spin, Playboy, Penthouse, Mother Jones, the Nation, New York, National Lampoon, Utne Reader, the Village Voice, the San Francisco Chronicle, the Los Angeles Times, the LA Weekly, New York Press, High Times and Funny Times.

His venues have ranged from the New Age Expo to the Skeptics Conference, from a Neo-Pagan Festival to the L.A. County Bar Association, from a Swingers Convention to the Brentwood Bakery, where members of the audience were each given a free pastry of their choice. Over the years, he has built up a cult following that has steadily been edging into mainstream awareness.

His reviews have been highly complimentary. The New York Times: “He is an expert at ferreting out hypocrisy and absurdism from the more solemn crannies of American culture.” The Los Angeles Times: “He has the uncanny ability to alter your perceptions permanently.” The San Francisco Chronicle: “Krassner is absolutely compelling. He has lived on the edge so long he gets his mail delivered there.”

He was head writer for an HBO special satirizing the 1980 presidential election campaign, did on-air commentary for the Fox network’s Wilton-North Report, and — a decade after poking fun at Ronald Reagan — was a writer on Ron Reagan’s syndicated late-night TV talk show.

Mercury Records released his first two comedy albums, We Have Ways of Making You Laugh and Brain Damage Control. Artemis Records released his next four: Sex, Drugs and the Antichrist: Paul Krassner at MIT, Campaign in the Ass, Irony Lives! and The Zen Bastard Rides Again.

His autobiography, Confessions of a Raving, Unconfined Nut: Misadventures in the Counter-Culture, published by Simon & Schuster, sold 30,000 copies. An expanded edition is now available on Paul’s website and also as an e-book on Kindle.

His other books include: The Winner of the Slow Bicycle Race: The Satirical Writings of Paul Krassner, with an introduction by Kurt Vonnegut; a trilogy of anthologies: Pot Stories For the Soul, with an introduction by Harlan Ellison, Psychedelic Trips For the Mind and Magic Mushrooms and Other Highs: From Toad Slime to Ecstasy; Impolite Interviews; Murder At the Conspiracy Convention and Other American Absurdities, with an introduction by George Carlin; One Hand Jerking: Reports From an Investigative Satirist, with a foreword by Harry Shearer and an introduction by Lewis Black; In Praise of Indecency: Dispatches From the Valley of Porn; and Who’s to Say What’s Obscene: Politics, Culture & Comedy in America Today, with a foreword by Arianna Huffington.

In May 2004, Krassner received an ACLU Uppie (Upton Sinclair) Award for dedication to freedom of expression. At the 14th annual Cannabis Cup in Amsterdam, he was inducted into the Counterculture Hall of Fame—my ambition,” he claims, “since I was three years old.”

And in December, 2010, the writers’ organization PEN honored him with their Lifetime Achievement Award. “I’m very happy to receive this award,” Paul concluded in his acceptance speech, “and even happier that it wasn’t posthumous.”