By Carl Hoffman

The Jerusalem Post

May 31, 2012

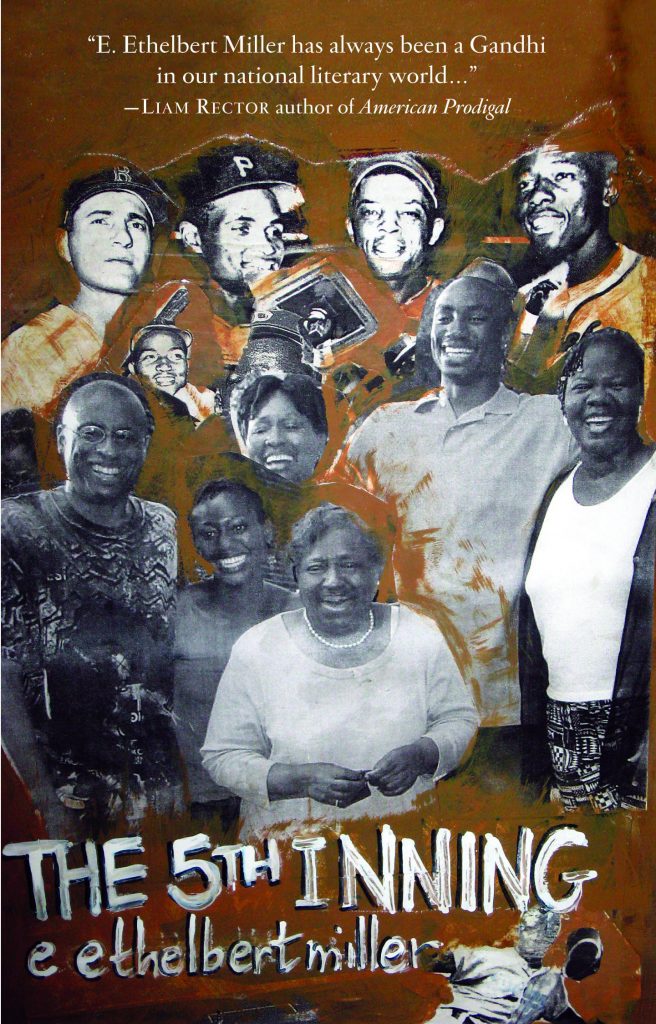

A self-described literary activist, recent Bar-Ilan guest E. Ethelbert Miller hopes his poetry brings together members of diverse populations.

Let’s see a show of hands, okay? How many of you have ever had a day proclaimed in your honor by the mayor of Washington? Has anyone ever been invited to the White House and honored by America’s first lady? Have you ever had something you wrote inscribed at the entrance of the Dupont Circle station of the Washington Metro, along with a poem by Walt Whitman?

For E. (Eugene) Ethelbert Miller, these are but a few of the honors, accolades and awards he has managed to accumulate over the course of a long, illustrious career.

Born 62 years ago in New York’s South Bronx, E. Ethelbert Miller is an African-American poet and teacher. He graduated Howard University with a BA in African American studies in 1972, and has served as director of the African American Studies Resource Center at Howard University since 1974. His collections of poetry include Andromeda (1974), The Land of Smiles and the Land of No Smiles (1974), Season of Hunger / Cry of Rain (1982), Where Are the Love Poems for Dictators? (1986), Whispers, Secrets and Promises (1998), and How We Sleep on the Nights We Don’t Make Love (2004).

Miller is the editor of poetry anthologies Women Surviving Massacres and Men (1977), In Search of Color Everywhere (1994)—a Book of the Month Club selection—and Beyond the Frontier (2002). He is also the author of the memoir Fathering Words: The Making of an African American Writer (2000). Miller has had days proclaimed in his honor by the mayor of Washington in 1979 and Jackson, Tennessee, in 2001; was made an “honorary citizen” by the mayor of Baltimore in 1994 and was honored at the White House by first lady Laura Bush in 2003. He was awarded a Fulbright grant in 2004, and again this year.

In addition to holding positions as scholar-in-residence at George Mason University and as the Jessie Ball DuPont Scholar at Emory and Henry College, Miller has conducted writing workshops for soldiers and the families of soldiers through Operation Homecoming. A self-described “literary activist,” Miller is on the board of the Institute for Policy Studies, a multi-issue “think tank.”

Miller recently spent two weeks in Israel as a guest of Bar-Ilan University, sponsored by the Fulbright Exchange Program. He spoke to Metro after a busy day of lectures and workshops.

You are often called a literary activist. What does this mean?

Well, first of all, I’m very active in terms of service to the field. I serve on a lot of literary boards. I work behind the scenes in terms of mentoring people. I serve on a lot of panels involved with getting people into residencies. I have been a judge for endowments and fellowships a number of times. I’m very much concerned with literary penetration, especially in Washington. I’m always encouraging writers to document what they do, to save their papers. I try to promote writers as much as possible. That’s what I do. If I were just concerned about my own career, I wouldn’t be as successful as I am. In Washington, DC, I’m very much concerned about cultural policy, looking at the impact that art can have on a community. You know, many people talk about simply economic development and the arts, but I feel that the quality of life—which is something you can’t simply measure—is also something that you have to consider.

Are you also a literary activist in your writing?

Very much so. I think I would probably be unique in terms of being a writer who for 19 years has served on the board of a progressive think tank in Washington, DC. I have one foot not only in the literary and cultural world, but also in the political world.

And I do have my beliefs that I try to live by. I’m a strong advocate in terms of what Martin Luther King was talking about in terms of the “beloved community,” about how you bring different groups of people together. So I’m a literary activist in trying to bring people together around issues of art, and around issues of culture.

And what brings you to Israel?

Well, this was my second Fulbright. I came here in 2004. This time I was a guest of Bar-Ilan University. I feel very blessed to work with their creative writing program. When I’m here, I try to make myself accessible to students as well as faculty members. There are a number of people here who I’m familiar with through their work, and there may be ways I can help them back in the US.

Are you able to mentor writers at Bar-Ilan while living in Washington?

I think so. For example, there are a couple of people here who I’ve published in my magazine. I’m one of the editors of Poet Lore, the oldest poetry magazine in the United States, established in 1889. It goes all the way back to Walt Whitman. This bears a tremendous responsibility, especially in terms of writers who want to be published in important journals. I feel that finding new voices and providing an outlet is something I very much want to do. And that’s what I did today at Bar-Ilan. My last class was a creative writing class, and I extended an invitation to the students there to submit work to my magazine. And if I can help them get published, I feel that I’ve had a good visit.

As a board member of the Institute for Policy Studies—a left-wing think tank not always in accord with the policies of the Israeli government—what is your take on the social and political situation here at present?

Well, I think that if you are concerned about peace in the world, you have to stay on top of what’s happening here in Israel. This is one of the major issues and challenges of our time. And we can’t shy away from the complexity of the problem. I think, for example, one of the things that I find here is that you have a lot of different voices within Israel. The country is extremely diverse. For example, I’ve been reading The Jerusalem Post during my visit and finding out more about the concerns and issues about the Ethiopians. It’s been interesting to read about some of the ways these issues are being addressed. I think that Israel is like the United States in that these are countries that to some extent are still experiments, still works in progress, in terms of how different kinds of people live together. In the United States, we’re still dealing with issues of equality for all citizens and how to deal with a multiracial society. So some of the things that you see happening in the United States are also happening here in Israel.

Do you have any advice or recommendations?

Well, as I say in one of my poems, whenever you wake up, you need to commit yourself to fixing something that’s broken. Even if it’s just an electric coffee pot. But you’ve got to live your life that way, even if it’s just small things you do. You have to believe that today is going to be better than yesterday. And always have hope for tomorrow. I did two classes at Bar-Ilan today. In one class, I was talking about the writer James Baldwin, who had visited Israel back in the early 1960s. And I was talking about some of the things he saw when he was here. The problem of having to bring people together does not disappear. We just have to be sure that we’re always up to discussing them and making things better. James Baldwin was here as a guest of the government. He not only visited Israel, but also spent a lot of time writing in Turkey.

Israel and Turkey are not often mentioned positively in the same sentence these days.

Well, you see, this is one of the challenges we face as writers. We have to change the narrative. We have to make sentences that contain words that maybe didn’t go together before. We maybe even have to create a new vocabulary.

Do you imagine Martin Luther King’s “beloved community” created here? Can often mutually hostile groups of people really be brought together?

The beloved community is something universal. The key thing here is that if you do not see the beloved community, then you must work to create it. I think it begins with the transformation of the individual. You have to be the change that you wish to see. It begins with the individual, and then comes the transformation of the community. But it’s hard work, and difficult. I think that the way to begin is for everyone who desires change to ask themselves at the end of the day, “Did I, in my small way, attempt to resolve a problem? What did I do today that made today better than yesterday?”

You are said to have found your poetic voice as a student at Howard University. What attracted you to poetry, as opposed to music, drama, or other forms of expression?

Well, I went to school and came of age in the late ’60s and early ’70s, so I was listening to Bob Dylan and Paul Simon. And they were turbulent times. The emphasis was on the social transformation of society. Poetry was for me the natural way to address those times and speak to some of those issues. And I think that even now, with the changes in our society today, and with technology influencing us in certain ways, poetry is even more important. I was talking to the students at Bar-Ilan’s creative writing program today that poetry slows you down. You can’t just read it like you read a Facebook page. You have to take time to read a poem. You have to read it several times, get meanings, look things up. Poetry will make you work. And if I read a poem in front of seven or eight people, some of them are going to say that “there are certain things here that I don’t understand.” Okay, that’s good. Now we have to work to make sure you understand. So it’s like lifting weights. The problem today is that people don’t want to lift the weights. I’ve got to tell them, “It’s okay. This is good for you. It will build your muscles up.”

You have written hundreds of poems. If only one of them survived into the distant future, which one would you want it to be?

I wrote a short poem that’s been translated into a number of languages.

It goes like this: “We are all Black poets at night.”

Initiated by United States Senator J. William Fulbright in 1946, the Fulbright Program is one of the world’s most prestigious and widely-known academic exchange programs. Its primary goal is to strengthen understanding between the American people and peoples of participating nations around the world through the exchange of students and lecturers at the highest academic level.

Here in Israel, Fulbright is managed by the United States-Israel Educational Foundation. Since the Foundation’s establishment by the US and Israeli governments in 1956, more than 1,200 Americans and 1,600 Israelis have participated in a variety of Fulbright student and academic staff exchanges.