By Shonda Buchanan

The Writer’s Chronicle

December, 2009

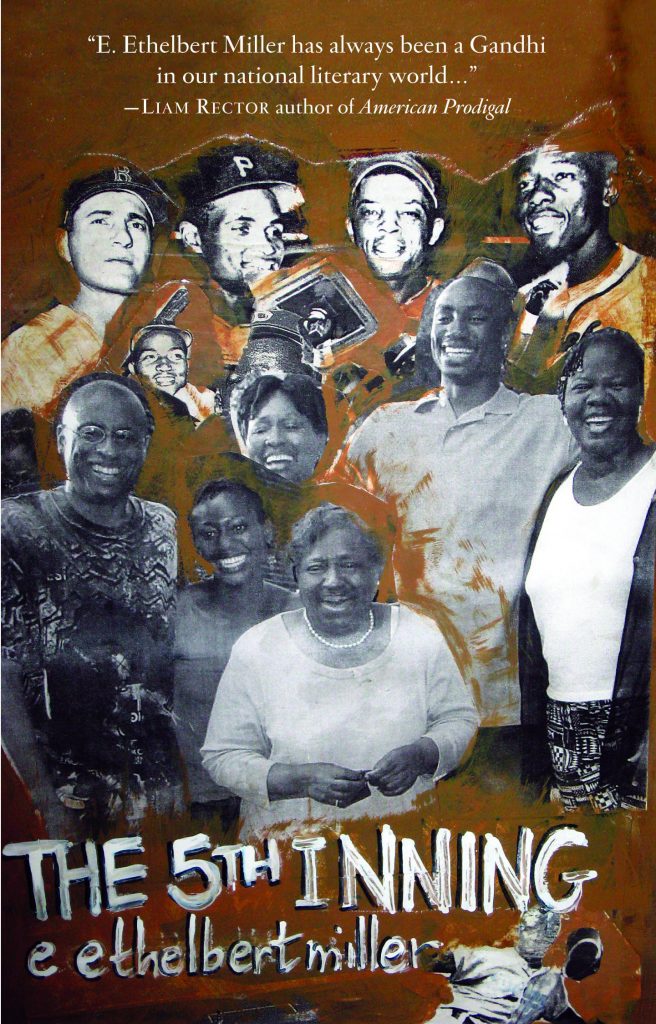

E. Ethelbert Miller is a well-known chronicler of black literary life in Washington, DC and across the country. He is a consummate documenter, as well as a writer of poetry and nonfiction. Eight years ago, Miller published a ground-breaking memoir, Fathering Words: The Making of an African American Writer, that captured the voice of a college-bound youth and his working-class father. As a literary activist, Miller is the board chairperson of the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS). He is a board member of The Writer’s Center and editor of Poet Lore magazine. Since 1974, he has been the director of the African American Resource Center at Howard University. Miller is the former chair of the Humanities Council of Washington, DC and a former core faculty member of the Bennington Writing Seminars at Bennington College. He is the advisory editor of the African American Review, founder of the Ascension Poetry Reading Series, and winner of the 1994 PEN Oakland Josephine Miles Award for his poetry anthology In Search of Color Everywhere. Miller has edited several anthologies, and is author of five collections of verse. His new memoir, The 5th Inning, a 165 page book, was published in March 2009 by Busboys & Poets.

E. Ethelbert Miller has found himself in the role of storyteller for his father, brother, and several friends simply by outliving them. In essence, writing The 5th Inning is tantamount to stealing third base, and entering certain moments and people into the record books for good.

Shonda Buchanan: Why use baseball as a motif?

E. Ethelbert Miller: When I look back on my life, I find that baseball was very important to me. It was the one thing that I was very passionate about from an early age. You had to actually stop me from playing and stop me from spending all my money on baseball cards. I grew up when many of the people whom I liked in terms of heroes—Sandy Koufax, Mickey Mantle, and Clete Boyer—were baseball players. I lived not far from Yankee Stadium. Oftentimes, one gravitates toward a sport, and that sport is something you live with your entire life. For me it’s baseball. When I was writing this second memoir, I said, okay, what is it that I really know? I think I know baseball best.

Buchanan: Why the fifth inning?

Miller: The fifth inning is an official complete game. It goes into the record books, and I’ve always looked at that as a metaphor for our lives. I look at so many of my friends, and people whom I don’t know, dying before they reach the age of sixty. Cancer, suicide, heart attack. So that became something I began to look at as I wrote The 5th Inning. Many games end because of rain or darkness. When I look at things I struggle against—depression, marriage, raising children—I see this sort of overcast. No matter how much people might see your life as being a beacon of light or you as being happy, you’re on your own on the mound. You’re in the batter’s box. You know the score.

Buchanan: How does this correlate with your work as a writer?

Miller: I think, right now, there is a certain sense of completion. What I’ve been doing for the last two years is boxing up my personal papers and giving them to the Givens Collection at the University of Minnesota and to George Washington University. I’m very conscious of what I’ve done and the importance of making material available to future scholars. I can go back and say, okay, these are all the things that went into Hoodoo Magazine, or these are what I used when I was editing In Search of Color Everywhere or Fathering Words. Here are documents, a tremendous amount of correspondence with people that I think are important for literary scholars. Going back and making sense out of what I saw as a very important period, especially in terms of Washington, DC history, and in terms of black literary history. National and international. When I look at what was taking place on the campus of Howard University that I was witness to—I look at the era, the early ’70s, as a golden era. Here I am, a young person in the early 1970s, and I’m meeting people like C.L.R. James, Haki Madhubuti, and Walter Rodney.

Buchanan: You talked about being a purveyor of art, and being a father, and ushering in the work of others. What about your own work as a writer?

Miller: I’m writing more. For a good part of my life, I was organizing. Some people don’t know that I wrote a memoir, and they aren’t familiar with my nonfiction work. At this particular point in my life, I feel it is time to really bring my work together, and make it available to the public. I’m writing better than ever before. And this goes back to baseball. You’re not going to hit the ball every time you get up. But there are times in your literary career when you know you can get on base with what you’ve written.

Buchanan: What is the book about for you?

Miller: This is a book that I felt I needed to write because of all the things I’ve experienced over the last few decades. Things that coincide with raising children and being in a second marriage. I needed to be honest. Many times people will say, “Oh, Ethelbert, you don’t seem happy, why don’t you change your life?” What I did when writing this book was to realize, okay, these were the pitches that I threw or the pitches that I faced. Baseball is very exact. The records are there. That’s how the influence of steroids taints these records, but when you look at baseball, you look at that box score. That tells you what happened. And the other thing about baseball is, you have to see the game. Similarly, you have to see my life on a daily basis because there are a lot of things that don’t show up in the box score. That’s something that I feel is there in this book—that level or degree of honesty. That’s why very early on I tell the reader, you won’t know if I’m throwing balls or strikes because it’s going to change. Some things will shock people. Sometimes I go off on a tangent, and that’s how this book is put together.

Buchanan: Did you realize anything differently in this second memoir than in the first? Fathering WordsThe 5th Inning feels more confining and even a bit sad. seems more like you trying to connect with your father, but there’s still a bit more optimism. You were at the beginning of your life even though it’s retrospective, while

Miller: I was very conscious of writing the first memoir. I knew I was telling someone about my beginnings. I knew exactly what I wanted to talk about. So there’s a chronology there you can follow, even though I’m going back and forth. It does cover South Bronx, to college, to becoming a writer.

Buchanan: Was Fathering Words about black men and depression, or fatherhood?

Miller: More family. I didn’t start out writing a book about depression. I wrote this book because I wanted to give praise and testimony to my father’s and brother’s lives. I felt that when they died, they had a lot remaining to offer life. For them to disappear without leaving anything behind—I felt that this is where I come in as a storyteller. What I can do is create the story. I can elevate their lives. I can take my father, who was a working class man in a post office, and elevate his life and make it much more heroic. The highest compliment to my having that skill is the success in keeping the memories of my father and brother alive. This is the power of the word. This is the power of creating myths. Whenever I go into a classroom and see young students reading about my brother and father, I know that I’ve achieved what I set out to do. Many people write books that come out but are never read. Every year, the audience for Fathering Words increases.

Buchanan: You write in The 5th Inning, “I need the strength to continue and the feeling that I’m writing what needs to find its air.” It feels as if sometimes in the narrative you are suffocating in your life. What are you trying to set free with this memoir?

Miller: As a person who is always dealing with documenting, I think what I’ve done, for good or bad, is document my life. I would not want someone to look at my books of poetry and come to a certain conclusion. I think if you read my poetry and my memoirs, you begin to find certain links. This is, I feel, pushing aside the silences that exist inside our relationships and the silences that many times exist within a home. In Fathering Words, I wrote about the dual sounds of music in a household. I grew up with that, but when I look at my own home, there is a certain level of silence. Everyone comes in and goes to their separate rooms. Sometimes, if it’s not a holiday, we take our meals in ones and twos, but not the four of us. Also, this is a book in which, by the time I’m finished, the family I’m writing about has changed. My son is off to college—he doesn’t come back that often. My daughter—it’s just a question of time before she transitions out. So it’s a different house than the one that I was reflecting back on. A memoir is always looking back.

Buchanan: How does your family view the memoir?

Miller: I sent each one a copy, and no one said anything. I sent the first copy to my sister. The second to my biographer, Julia Galbus, in Indiana. Those were the first people who got copies. My sister was very saddened by it. She felt it was very painful and said, “I want to know more.” I didn’t send her the entire thing. I incorporated what Julia Galbus said into the memoir because it was a whole thing about darkness. That was very helpful for me to realize that I don’t have to write against this. If it proceeds in this direction, then it’s just going to be a dark book.

Buchanan: It’s a nonlinear structure, much like the first book.

Miller: It’s nonlinear, even though it reads in such a way you get a sense of what I’m processing. You get a sense of some of the things happening while I’m at Virginia Center for the Creative Arts (VCCA). I included my friend Kay Ruane, who is a painter. She’s the person who survived an airplane crash. What I did was no different than what a visual artist would do in terms of finding objects and assembling them. That’s how this memoir was written. I think it makes it very rich for someone who can come back and read it in such a way that he or she sees the jokes I’m playing. For instance, there are places where I’m lifting lines from Bob Dylan. If they know Dylan, they know the line. I consciously added a lot of baseball, which I wouldn’t have had time to do if I had not gone to VCCA. I’m talking about specific players. That’s where I wanted to go deeper into the metaphor.

Buchanan: Your favorite players representing certain aspects of your life?

Miller: Exactly, or they become players that play against my life. I look at Pumpsie Green, the first black player for the Red Sox. No one remembers Pumpsie Green or Tony Conigliaro, whose life was tragically interrupted by getting hit in the face. By bringing those names to the forefront, a person who is really into baseball and giving it a serious critical read will realize, “Oh, Ethelbert is talking about Carl Yastrzemski or Bill Monbouquette. Why is he referring to those names?” If someone comes along and wants to look at my life or poems now, they would have to look at my blog. Some of my best writing is caught up in there. And what holds it together is my admiration for the baseball player Ichiro Suzuki. He’s there throughout my entire blog. It’s not different than being influenced by Ezra Pound or Whitman. So we see these connections. In a close reading, someone will ask what does this person represent here?

Buchanan: You don’t answer all the questions you raise for the reader. Why?

Miller: I think, for both memoirs, if you took a marker and circle the questions marks, there are quite a few. I’m conscious of that because I don’t know the answers, and sometimes it’s a riff on life. I want the reader not to just think about my life, but to think about their own lives. “Well, why did you do that?” Well, what would you do? If I’ve done my job, you as the reader reflect and make these connections. The fifth inning now for my sister has become a part of her vocabulary when someone dies. Oh, the fifth inning. What happens is it begins to resonate outside of baseball, and I think if I can do that as a writer then I’ve done a good job.

Buchanan: Do you feel that when you reflect back on your life and work, you have become your father?

Miller: I think so. But I think I’ve done some things that he would be proud of. I’ve been able to get my children to where they are today. But I’ve never worked as hard as my father. I’ve never pushed my body physically.

Buchanan: But writing is a physical act.

Miller: Writing is physical. You’ve got to really sit there and keep your body going, and if you’re not disciplined, it doesn’t happen. Writing isn’t easy. Re-writing isn’t easy. You’ve got to make your free throws, you’ve got to practice. You look at a line, and you’ve got to look at that line over and over again. If you’re going to give up, then you’re not the writer.

Buchanan: Give me an example.

Miller: This summer, I went to VCCA and I realized that many of my friends were living the writer’s life. I saw this when I was working up at Bennington. The residency would be ending, and my fellow colleagues were going off to Italy to write. It’s no wonder they have a book every two years. I could go off to France to write, to Italy to write. Have some bread and wine. But you look at yourself—you’re in your fifties, and you realize you’re not living the writer’s life. You’re not taking advantage of some of these things. I look at my long-term relationship with Howard, and when I look at how some schools have never embraced writers, I see how that’s continued with me. If I look at how Sterling Brown was treated, or especially Julian Mayfield—these people are given no institutional support. Or as I remember Stephen Henderson used to say, “Léon Damas is walking across the campus of Howard University. No one knows he’s one of the founders of Negritude.” And if they did, they wouldn’t care. That tells you something about the campus. A part of me says, “I’m going to write myself out of Howard.” And another part of me says, “I’m going to stay there until I get my due.” See, that’s my father: “The longest day hasn’t ended.”

Buchanan: Is what happened, and is happening to you, indicative of the role of the artist in academia?

Miller: No. I’m a literary activist. I don’t take that nonsense. I’ve looked at writers. I’ll begin with Sterling Brown. People used to say, “Oh, he’s the poet laureate of Washington, DC.” He wasn’t. We went down and made him the poet laureate. I remember when he had his proclamation, and he was getting in his car, he was a happy guy. We had it on Capitol Hill. We had to bribe him to get him out of his house, but he was happy. It was official.

Buchanan: Unlike Langston Hughes being the unofficial poet laureate of Harlem.

Miller: Right. What I feel is important to do—I have all these people’s papers—is to make sure these papers get into the hands of scholars. This is what I get angry about. The people running historically black colleges don’t protect the stuff. They don’t have the funds or the staff. Or they want to sell someone’s paintings. They don’t appreciate what they have.

Buchanan: How long have you been at Howard?

Miller: I’ve been at Howard as a full employee since 1974.

Buchanan: Have you taught at Howard?

Miller: I’ve never been a professor there. I’ve never taught at Howard. I’ve run the African American Resource Center. I’ve taught at University of Nevada Las Vegas, American University, George Mason, Emory, Henry College, and Bennington.

Buchanan: Why never at Howard?

Miller: Because I didn’t go on to get all those degrees, and the reason for that is I knew what I wanted to do. There was a point when I came back from UNLV where I was treated very well, and came back to Howard. They were trying to phase out my position because there was this push to get me to go back to school. That’s for their own interest. I told the dean, “This may sound arrogant, but you guys study literature; I make it.” To me, I try to advance the field of literature. I’m not looking at some footnotes. I look at the things I’ve done that I don’t even take credit for. When I went to UNLV, I had to put together a resume for the first time. I’ve never packaged myself as a media person even though I do radio shows and NPR. For example, the Humanities Council now runs almost all of my shows that I recorded when I worked for them at UDC Station.

Buchanan: You said in the book, “I once wrote an essay in a magazine in which I mentioned that my deepest fear was to be a survivor. I don’t want to be the person discovered after being underground and trapped for fourteen hours. I don’t want to be the person lost in the mountains and freezing for days. I’m just a guy in a second marriage.” Aren’t you surviving?

Miller: That’s a good read of that.

Buchanan: What are you surviving?

Miller: Everything. Relationships, Howard. I look at the climate change. I look at New Orleans, and I’ve been telling people that the concept of home has become almost obsolete. That we almost have to give that up. That many of us are going to be on the move, or you can’t assume that everything here is going to stay.

Buchanan: Scott Russell Sanders might have something to say about that, too.

Miller: As writers, for example, the expression “I’m going to call home” makes no sense because you call your mother and she’s on a mobile phone. We’re always recreating new spaces or claiming space to call our home, but it’s not permanent.

Buchanan: So what is your home? Where is it?

Miller: Here. Maybe this will be a place where a visiting writer will stay one day. That would be the ideal thing.

Buchanan: You wrote in The 5th Inning that you’ve spoken and written so much about love that you now need to begin to love yourself and your aloneness. When will that happen?

Miller: It’s always a process. Each day I struggle with that.

Buchanan: What would you tell budding writers now, after a lifetime of writing? And what would you tell budding memoirists?

Miller: It’s important to keep tradition alive. Try and document as much as possible. This will help to reclaim memory in the future. I’m afraid we have become a people who no longer value the book. I see reading books as being fundamental to the soul’s well-being. To read alone or read aloud is as important as meditation or prayer. It is also why we write. I would remind all budding writers to “always be closing.” ABC. That was the mantra my friend Liam Rector echoed throughout my tenure, teaching in the Bennington Writing Seminars. Finally, it’s important for all young writers to understand that they have the capability to shape history and not simply be shaped by it. I would remind writers to see themselves as witnesses, and to always speak the truth to the people, as well as truth to power. A love of language should be as strong as the love for life.